What is algebra? Naively speaking algebra gives us the ability to perform calculations with numbers and symbols. Abstract algebra treats symbols as elements of a vector space: they can be multiplied by scalars and added to each other. But what makes algebras stand appart from linear spaces is the presence of vector multiplication: a bilinear product of vectors whose result is another vector (as opposed to inner product, which produces a scalar). Complex numbers, for instance, can be described as 2-d vectors, whose components are the real and the imaginary parts.

But nothing prepares you for this definition of F-algebra from the Haskell package Control.Functor.Algebra:

type Algebra f a = f a -> a

In this post I will try to bridge the gap between traditional algebras and more powerful F-algebras. F-algebras reduce the notion of an algebra to the bare minimum. It turns out that the three basic ingredients of an algebra are: a functor, a type, and a function. It always amazes me how much you can do with so little. In particular I will explain a very general way of evaluating arbitrary expressions using catamorphisms, which reduces to foldr when applied to lists (which can also be looked at as simple F-algebras).

The Essence of Algebra

There are two really essential aspects of an algebra:

- The ability to form expressions and

- The ability to evaluate these expressions

The Essence of Expression

The standard way of generating expressions is to use grammars. Here’s an example of a grammar in Haskell:

data Expr = Const Int

| Add Expr Expr

| Mul Expr Expr

Like most non-trivial grammars, this one is defined recursively. You may think of Expr as a self-similar fractal. An Expr, as a type, contains not only Const Int, but also Add and Mult, which inside contain Exprs, and so on. It’s trees all the way down.

But recursion can be abstracted away to uncover the real primitives behind expressions. The trick is to define a non-recursive function and then find its fixed point.

Since here we are dealing with types, we have to define a type function, otherwise known as type constructor. Here’s the non-recursive precursor of our grammar (later you’ll see that the F in ExprF stands for functor):

data ExprF a = Const Int

| Add a a

| Mul a a

The fractally recursive structure of Expr can be generated by repeatedly applying ExprF to itself, as in ExprF (ExprF (ExprF a))), etc. The more times we apply it, the deeper trees we can generate. After infinitely many iterations we should get to a fixed point where further iterations make no difference. It means that applying one more ExprF would’t change anything — a fixed point doesn’t move under ExprF. It’s like adding one to infinity: you get back infinity.

In Haskell, we can express the fixed point of a type constructor f as a type:

newtype Fix f = In (f (Fix f))

If you look at this formula closely, it is exactly what I said: Fix f is the type you get by applying f to itself. It’s a fixed point of f. (In the literature you’ll sometimes see Fix called Mu.)

We only need one generic recursive type, Fix, to be able to crank out other recursive types from (non-recursive) type constructors.

One thing to observe about the data constructor of Fix: In can be treated as a function that takes an element of type f (Fix f) and produces a Fix f:

In :: f (Fix f) -> Fix f

We’ll use this function later.

With that, we can redefine Expr as a fixed point of ExprF:

type Expr = Fix ExprF

You might ask yourself: Are there any values of the type Fix ExprF at all? Is this type inhabited? It’s a good question and the answer is yes, because there is one constructor of ExprF that doesn’t depend on a. This constructor is Const Int. We can bootstrap ourselves because we can always create a leaf Expr, for instance:

val :: Fix ExprF val = In (Const 12)

Once we have that ability, we can create more and more complex values using the other two constructors of ExprF, as in:

testExpr = In $ (In $ (In $ Const 2) `Add`

(In $ Const 3)) `Mul` (In $ Const 4)

The Essence of Evaluation

Evaluation is a recipe for extracting a single value from an expression. In order to evaluate expressions which are defined recursively, the evaluation has to proceed recursively as well.

Again, recursion can be abstracted away — all we really need is an evaluation strategy for each top level construct (generated, for instance, by ExprF) and a way to evaluate its children. Let’s call this non-recursive top-level evaluator alg and the recursive one (for evaluating children) eval. Both alg and eval return values of the same type, a.

First, we need to be able to map eval over the children of an expression. Did somebody mentioned mapping? That means we need a functor!

Indeed, it’s easy to convince ourselves that our ExprF is a functor:

instance Functor ExprF where

fmap f (Const i) = Const i

fmap f (left `Add` right) = (f left) `Add` (f right)

fmap f (left `Mul` right) = (f left) `Mul` (f right)

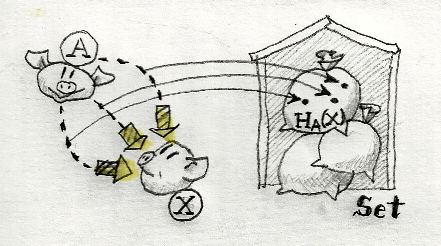

An F-algebra is built on top of a functor — any functor. (Strictly speaking, an endofunctor: it maps a given category into itself — in our examples the category refers to Hask — the category of all Haskell types).

Now suppose we know how to evaluate all the children of Add and Mul in an Expr, giving us values of some type a. All that’s left is to evaluate (Add a a) and (Mul a a) in ExprF a. (We also need to evaluate Const Int, but that doesn’t involve recursion.)

Here’s an example of such an evaluator that produces Int values:

alg :: ExprF Int -> Int alg (Const i) = i alg (x `Add` y) = x + y alg (x `Mul` y) = x * y

(Notice that we are free to add and multiply x and y, since they are just Ints.)

What I have done here is to pick one particular type, Int, as my evaluation target. This type is called the carrier type of the algebra. I then defined a function alg from the image of Int under the functor ExprF back to Int.

Just to show that the carrier type is arbitrary, let me define another evaluator that returns a string:

alg' :: ExprF String -> String alg' (Const i) = [chr (ord 'a' + i)] alg' (x `Add` y) = x ++ y alg' (x `Mul` y) = concat [[a, b] | a <- x, b <- y]

F-Algebras

We are now ready to define F-algebras in the most general terms. First I’ll use the language of category theory and then quickly translate it to Haskell.

An F-algebra consists of:

- an endofunctor F in a category C,

- an object A in that category, and

- a morphism from F(A) to A.

An F-algebra in Haskell is defined by a functor f, a carrier type a, and a function from (f a) to a. (The underlying category is Hask.)

Right about now the definition with which I started this post should start making sense:

type Algebra f a = f a -> a

For a given functor f and a carrier type a the alebra is defined by specifying just one function. Often this function itself is called the algebra, hence my use of the name alg in previous examples.

Back to our conrete example, the functor is ExprF, the carrier type is Int and the function is alg:

-- My simple algebra type SimpleA = Algebra ExprF Int alg :: SimpleA alg (Const i) = i alg (x `Add` y) = x + y alg (x `Mul` y) = x * y

The only thing that’s still missing is the definition of the function eval, which takes care of evaluating children of an expression. It turns out this function can be defined in a very general form. To do that we’ll need to familiarize ourselves with the notion of the initial algebra.

Initial Algebras

There are many algebras based on a given functor (I’ve shown you two so far). But there is one algebra to bind them all — the initial algebra. In fact you’ve already seen elements of it. Remember the Fix type function?

newtype Fix f = In (f (Fix f))

Given any functor f it defines a new unique type Fix f. We will now lift ourselves by the bootstraps. We’ll use this type as a carrier in the definition of another algebra. This will turn out to be our initial algebra.

First, let’s go back to our example and, instead of using Int or String, use (Fix ExprF) as the carrier type:

type ExprInitAlg = Algebra ExprF (Fix ExprF)

We have the functor and the carrier type. To complete the triple we need to define a function with the following signature:

ex_init_alg :: ExprF (Fix ExprF) -> Fix ExprF

Guess what, we already have a function of this type. It’s the constructor of Fix:

ex_init_alg = In

(Replace f with ExprF in the definition of Fix to see that the type signatures match.)

But wait! What does this “evaluator” evaluate? Given (ExprF Expr) it produces an Expr. For instance, when given,

Add (In $ Const 2) (In $ Const 3)

it will produce an Expr:

In $ Add (In $ Const 2) (In $ Const 3)

This evaluator doesn’t reduce anything like the evaluators we’ve been using so far. It is not lossy. It preserves all the information passed to it as input. [Note: In fact, Lambek’s lemma states that the initial algebra is an isomorphism.] In comparison, all other evaluators potentially lose some information. They return some kind of summary of the information encoded in the data structure. In this sense, the algebra we have just defined is at least as powerful as all other algebras based on the same functor. That’s why it’s called the initial algebra.

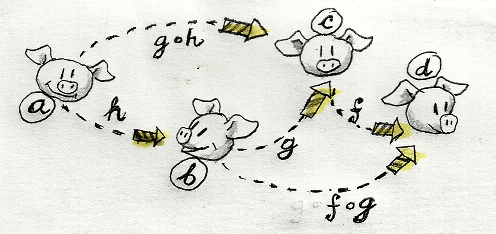

The word initial has a special meaning in category theory. The initial algebra has the property that there exists a (unique) homomophism from it to any other algebra based on the same functor.

A homomoprhism is a mapping that preserves certain structure. In the case of algebras, a homomorphism has to preserve the algebraic structure. An algebra consists of a functor, a carrier type, and an evaluator. Since we are keeping the functor fixed, we only need to map carrier types and evaluators.

In fact, a homomorphism of algebras is fully specified by a function that maps one carrier to another and obeys certain properties. Since the carrier of the intial algebra is Fix f, we need a function:

g :: Fix f -> a

where a is the carrier for the other algebra. That algebra has an evaluator alg with the signature:

alg :: f a -> a

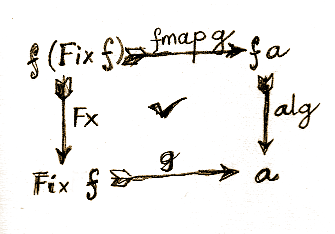

The special property g has to obey is that it shouldn’t matter whether we first use the initial algebra’s evaluator and then aply g, or first apply g (through fmap) and then the second algebra’s evaluator, alg. Let’s check the types involved to convince ourselves that this requirement makes sense.

The first evaluator uses In to go from f (Fix f) to Fix f. Then g takes Fix f to a.

The alternate route uses fmap g to map f (Fix f) to f a, followed by alg from f a to a. Notice that this is the first time that we used the functorial property of f. It allowed us to lift the function g to fmap g.

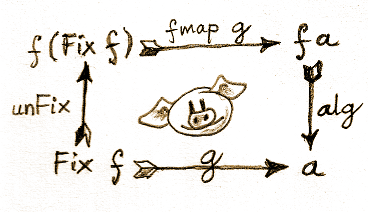

The crucial observation is that In is a losless transformation and it can be easily inverted. The inverse of In is unFix:

unFix :: Fix f -> f (Fix f) unFix (In x) = x

With one reversal of the arrow In to unFix, it’s easy to see that going the route of g is the same as taking the detour through unFix, followed by fmap g, and then alg:

g = alg . (fmap g) . unFix

We can use this equation as a recursive definition of g. We know that this definition converges because the application of g through fmap deals with subtrees of the original tree, and they are strictly smaller than the original tree.

We can abstract the evaluation further by factoring out the dependence on alg (redefining g = cata alg):

cata :: Functor f => (f a -> a) -> Fix f -> a cata alg = alg . fmap (cata alg) . unFix

The result is a very generic function called a catamorphism. We have constructed the catamorphism from an algebra in order to prove that the fixed point of this algebra’s functor is the initial algebra. But wait, haven’t we just created the recursive evaluator we’ve been looking for?

Catamorphisms

Look again at the type signature of the catamorphism with some additional (redundant) parentheses:

cata :: Functor f => (f a -> a) -> (Fix f -> a)

It takes an arbitrary algebra, which is a non-recursive function f a -> a, and returns an evaluator function, (Fix f -> a). This function takes an expression of the type Fix f and evaluates it down to type a. A catamorphism lets us evaluate arbitrarily nested expressions!

Let’s try it with our simple functor ExprF, which we used to generate nested expressions of the type Fix ExprF.

We have already defined an alg for it:

type SimpleA = Algebra ExprF Int alg :: SimpleA alg (Const i) = i alg (x `Add` y) = x + y alg (x `Mul` y) = x * y

So our full-blown evaluator is just:

eval :: Fix ExprF -> Int -- eval = cata alg = alg . fmap (cata alg) . unFix eval = alg . fmap eval . unFix

Let’s analyze it: First, unFix allows us to peek at the top level of the input expression: It’s either a leaf Const i or an Add or Mul whose children are, again, full-blown expression, albeit one degree shallower. We evaluate the children by recursively applying eval to them. We end up with a single level tree whose leaves are now evaluated down to Ints. That allows us to apply alg and get the result.

You can test this on a sample expression:

testExpr = In $ (In $ (In $ Const 2) `Add`

(In $ Const 3)) `Mul` (In $ Const 4)

You can run (and modify) this code online in the School of Haskell version of this blog.

{-# LANGUAGE DeriveFunctor #-}

data ExprF r = Const Int

| Add r r

| Mul r r

deriving Functor

newtype Fix f = In (f (Fix f))

unFix :: Fix f -> f (Fix f)

unFix (In x) = x

cata :: Functor f => (f a -> a) -> Fix f -> a

cata alg = alg . fmap (cata alg) . unFix

alg :: ExprF Int -> Int

alg (Const i) = i

alg (x `Add` y) = x + y

alg (x `Mul` y) = x * y

eval :: Fix ExprF -> Int

eval = cata alg

testExpr = In $

(In $ (In $ Const 2) `Add` (In $ Const 3)) `Mul`

(In $ Const 4)

main = print $ eval $ testExpr

foldr

Traversing and evaluating a recursive data structure? Isn’t that what foldr does for lists?

Indeed, it’s easy to create algebras for lists. We start with a functor:

data ListF a b = Nil | Cons a b

instance Functor (ListF a) where

fmap f Nil = Nil

fmap f (Cons e x) = Cons e (f x)

The first type argument to ListF is the type of the element, the second is the one we will recurse into.

Here’s a simple algebra with the carrier type Int:

algSum :: ListF Int Int -> Int algSum Nil = 0 algSum (Cons e acc) = e + acc

Using the constructor In we can recursively generate arbitrary lists:

lst :: Fix (ListF Int) lst = In $ Cons 2 (In $ Cons 3 (In $ Cons 4 (In Nil)))

Finally, we can evaluate our list using our generic catamorphism:

cata algSum lst

Of course, we can do exactly the same thing with a more traditional list and foldr:

foldr (\e acc -> e + acc) 0 [2..4]

You should see the obvious paralles between the definition of the algSum algebra and the two arguments to foldr. The difference is that the algebraic approach can be generalized beyond lists to any recursive data structure.

Here’s the complete list example:

newtype Fix f = In (f (Fix f))

unFix :: Fix f -> f (Fix f)

unFix (In x) = x

cata :: Functor f => (f a -> a) -> Fix f -> a

cata alg = alg . fmap (cata alg) . unFix

data ListF a b = Nil | Cons a b

instance Functor (ListF a) where

fmap f Nil = Nil

fmap f (Cons e x) = Cons e (f x)

algSum :: ListF Int Int -> Int

algSum Nil = 0

algSum (Cons e acc) = e + acc

lst :: Fix (ListF Int)

lst = In $ Cons 2 (In $ Cons 3 (In $ Cons 4 (In Nil)))

main = do

print $ (cata algSum) lst

print $ foldr (\e acc -> e + acc) 0 [2, 3, 4]

Conclusion

Here are the main points of this post:

- Just like recursive functions are defined as fixed points of regular functions, recursive (nested) data structures can be defined as fixed points of regular type constructors.

- Functors are interesting type constructors because they give rise to nested data structures that support recursive evaluation (generalized folding).

- An F-algebra is defined by a functor

f, a carrier typea, and a function fromf atoa. - There is one initial algebra that maps into all algebras defined over a given functor. This algebra’s carrier type is the fixed point of the functor in question.

- The unique mapping between the initial algebra and any other algebra over the same functor is generated by a catamorphism.

- Catamophism takes a simple algebra and creates a recursive evaluator for a nested data structure (the fixed point of the functor in question). This is a generalization of list folding to arbitrary recursive data structures.

Acknowledgment

I’m greatful to Gabriel Gonzales for reviewing this post. Gabriel made an interesting observation:

“Actually, even in Haskell recursion is not completely first class because the compiler does a terrible job of optimizing recursive code. This is why F-algebras and F-coalgebras are pervasive in high-performance Haskell libraries like vector, because they transform recursive code to non-recursive code, and the compiler does an amazing job of optimizing non-recursive code.”

Bibliography

Most examples in my post were taken from the first two publications below:

- Fixing GADTs by Tim Philip Williams.

- Advanced Functional Programming, Tim Sheard’s course notes.

- Functional Programming with Bananas, Lenses, Envelopes, and Barbed Wire by Erik Meijer, Maarten Fokkinga, and Ross Paterson.

- Recursive types for free! by Philip Wadler

- Catamorphisms in Haskell Wiki