This is part 9 of Categories for Programmers. Previously: Functoriality. See the Table of Contents.

So far I’ve been glossing over the meaning of function types. A function type is different from other types.

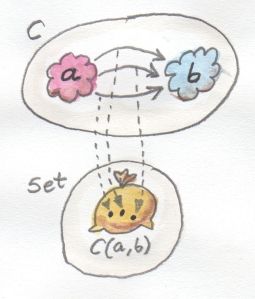

Take Integer, for instance: It’s just a set of integers. Bool is a two element set. But a function type a->b is more than that: it’s a set of morphisms between objects a and b. A set of morphisms between two objects in any category is called a hom-set. It just so happens that in the category Set every hom-set is itself an object in the same category —because it is, after all, a set.

The same is not true of other categories where hom-sets are external to a category. They are even called external hom-sets.

It’s the self-referential nature of the category Set that makes function types special. But there is a way, at least in some categories, to construct objects that represent hom-sets. Such objects are called internal hom-sets.

Universal Construction

Let’s forget for a moment that function types are sets and try to construct a function type, or more generally, an internal hom-set, from scratch. As usual, we’ll take our cues from the Set category, but carefully avoid using any properties of sets, so that the construction will automatically work for other categories.

A function type may be considered a composite type because of its relationship to the argument type and the result type. We’ve already seen the constructions of composite types — those that involved relationships between objects. We used universal constructions to define a product type and a coproduct types. We can use the same trick to define a function type. We will need a pattern that involves three objects: the function type that we are constructing, the argument type, and the result type.

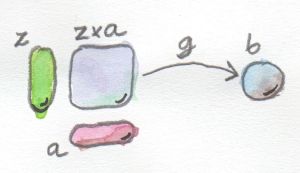

The obvious pattern that connects these three types is called function application or evaluation. Given a candidate for a function type, let’s call it z (notice that, if we are not in the category Set, this is just an object like any other object), and the argument type a (an object), the application maps this pair to the result type b (an object). We have three objects, two of them fixed (the ones representing the argument type and the result type).

We also have the application, which is a mapping. How do we incorporate this mapping into our pattern? If we were allowed to look inside objects, we could pair a function f (an element of z) with an argument x (an element of a) and map it to f x (the application of f to x, which is an element of b).

In Set we can pick a function f from a set of functions z and we can pick an argument x from the set (type) a. We get an element f x in the set (type) b.

But instead of dealing with individual pairs (f, x), we can as well talk about the whole product of the function type z and the argument type a. The product z×a is an object, and we can pick, as our application morphism, an arrow g from that object to b. In Set, g would be the function that maps every pair (f, x) to f x.

So that’s the pattern: a product of two objects z and a connected to another object b by a morphism g.

Is this pattern specific enough to single out the function type using a universal construction? Not in every category. But in the categories of interest to us it is. And another question: Would it be possible to define a function object without first defining a product? There are categories in which there is no product, or there isn’t a product for all pairs of objects. The answer is no: there is no function type, if there is no product type. We’ll come back to this later when we talk about exponentials.

Let’s review the universal construction. We start with a pattern of objects and morphisms. That’s our imprecise query, and it usually yields lots and lots of hits. In particular, in Set, pretty much everything is connected to everything. We can take any object z, form its product with a, and there’s going to be a function from it to b (except when b is an empty set).

That’s when we apply our secret weapon: ranking. This is usually done by requiring that there be a mapping between candidate objects — a mapping that somehow factorizes our construction. In our case, we’ll decree that z together with the morphism g from z×a to b is better than some other z' with its own application g', if and only if there is a mapping h from z' to z such that the application of g' factors through the application of g. (Hint: Read this sentence while looking at the picture.)

Now here’s the tricky part, and the main reason I postponed this particular universal construction till now. Given the morphism h :: z'-> z, we want to close the diagram that has both z' and z crossed with a. What we really need, given the mapping h from z' to z, is a mapping from z'×a to z×a. And now, after discussing the functoriality of the product, we know how to do it. Because the product itself is a functor (more precisely an endo-bi-functor), it’s possible to lift pairs of morphisms. In other words, we can define not only products of objects but also products of morphisms.

Since we are not touching the second component of the product z'×a, we will lift the pair of morphisms (h, id), where id is an identity on a.

So, here’s how we can factor one application, g, out of another application g':

g' = g ∘ (h × id)

The key here is the action of the product on morphisms.

The third part of the universal construction is selecting the object that is universally the best. Let’s call this object a⇒b (think of this as a symbolic name for one object, not to be confused with a Haskell typeclass constraint — I’ll discuss different ways of naming it later). This object comes with its own application — a morphism from (a⇒b)×a to b — which we will call eval. The object a⇒b is the best if any other candidate for a function object can be uniquely mapped to it in such a way that its application morphism g factorizes through eval. This object is better than any other object according to our ranking.

The definition of the universal function object. This is the same diagram as above, but now the object a⇒b is universal.

Formally:

A function object from a to b is an object a⇒b together with the morphism

eval :: ((a⇒b) × a) -> b such that for any other object g :: z × a -> b there is a unique morphism h :: z -> (a⇒b) that factors g = eval ∘ (h × id) |

Of course, there is no guarantee that such an object a⇒b exists for any pair of objects a and b in a given category. But it always does in Set. Moreover, in Set, this object is isomorphic to the hom-set Set(a, b).

This is why, in Haskell, we interpret the function type a->b as the categorical function object a⇒b.

Currying

Let’s have a second look at all the candidates for the function object. This time, however, let’s think of the morphism g as a function of two variables, z and a.

g :: z × a -> b

Being a morphism from a product comes as close as it gets to being a function of two variables. In particular, in Set, g is a function from pairs of values, one from the set z and one from the set a.

On the other hand, the universal property tells us that for each such g there is a unique morphism h that maps z to a function object a⇒b.

h :: z -> (a⇒b)

In Set, this just means that h is a function that takes one variable of type z and returns a function from a to b. That makes h a higher order function. Therefore the universal construction establishes a one-to-one correspondence between functions of two variables and functions of one variable returning functions. This correspondence is called currying, and h is called the curried version of g.

This correspondence is one-to-one, because given any g there is a unique h, and given any h you can always recreate the two-argument function g using the formula:

g = eval ∘ (h × id)

The function g can be called the uncurried version of h.

Currying is essentially built into the syntax of Haskell. A function returning a function:

a -> (b -> c)

is often thought of as a function of two variables. That’s how we read the un-parenthesized signature:

a -> b -> c

This interpretation is apparent in the way we define multi-argument functions. For instance:

catstr :: String -> String -> String catstr s s’ = s ++ s’

The same function can be written as a one-argument function returning a function — a lambda:

catstr’ s = \s’ -> s ++ s’

These two definitions are equivalent, and either can be partially applied to just one argument, producing a one-argument function, as in:

greet :: String -> String greet = catstr “Hello “

Strictly speaking, a function of two variables is one that takes a pair (a product type):

(a, b) -> c

It’s trivial to convert between the two representations, and the two (higher-order) functions that do it are called, unsurprisingly, curry and uncurry:

curry :: ((a, b)->c) -> (a->b->c) curry f a b = f (a, b)

and

uncurry :: (a->b->c) -> ((a, b)->c) uncurry f (a, b) = f a b

Notice that curry is the factorizer for the universal construction of the function object. This is especially apparent if it’s rewritten in this form:

factorizer :: ((a, b)->c) -> (a->(b->c)) factorizer g = \a -> (\b -> g (a, b))

(As a reminder: A factorizer produces the factorizing function from a candidate.)

In non-functional languages, like C++, currying is possible but nontrivial. You can think of multi-argument functions in C++ as corresponding to Haskell functions taking tuples (although, to confuse things even more, in C++ you can define functions that take an explicit std::tuple, as well as variadic functions, and functions taking initializer lists).

You can partially apply a C++ function using the template std::bind. For instance, given a function of two strings:

std::string catstr(std::string s1, std::string s2) {

return s1 + s2;

}

you can define a function of one string:

using namespace std::placeholders;

auto greet = std::bind(catstr, "Hello ", _1);

std::cout << greet("Haskell Curry");

Scala, which is more functional than C++ or Java, falls somewhere in between. If you anticipate that the function you’re defining will be partially applied, you define it with multiple argument lists:

def catstr(s1: String)(s2: String) = s1 + s2

Of course that requires some amount of foresight or prescience on the part of a library writer.

Exponentials

In mathematical literature, the function object, or the internal hom-object between two objects a and b, is often called the exponential and denoted by ba. Notice that the argument type is in the exponent. This notation might seem strange at first, but it makes perfect sense if you think of the relationship between functions and products. We’ve already seen that we have to use the product in the universal construction of the internal hom-object, but the connection goes deeper than that.

This is best seen when you consider functions between finite types — types that have a finite number of values, like Bool, Char, or even Int or Double. Such functions, at least in principle, can be fully memoized or turned into data structures to be looked up. And this is the essence of the equivalence between functions, which are morphisms, and function types, which are objects.

For instance a (pure) function from Bool is completely specified by a pair of values: one corresponding to False, and one corresponding to True. The set of all possible functions from Bool to, say, Int is the set of all pairs of Ints. This is the same as the product Int × Int or, being a little creative with notation, Int2.

For another example, let’s look at the C++ type char, which contains 256 values (Haskell Char is larger, because Haskell uses Unicode). There are several functions in the part of the C++ Standard Library that are usually implemented using lookups. Functions like isupper or isspace are implemented using tables, which are equivalent to tuples of 256 Boolean values. A tuple is a product type, so we are dealing with products of 256 Booleans: bool × bool × bool × ... × bool. We know from arithmetics that an iterated product defines a power. If you “multiply” bool by itself 256 (or char) times, you get bool to the power of char, or boolchar.

How many values are there in the type defined as 256-tuples of bool? Exactly 2256. This is also the number of different functions from char to bool, each function corresponding to a unique 256-tuple. You can similarly calculate that the number of functions from bool to char is 2562, and so on. The exponential notation for function types makes perfect sense in these cases.

We probably wouldn’t want to fully memoize a function from int or double. But the equivalence between functions and data types, if not always practical, is there. There are also infinite types, for instance lists, strings, or trees. Eager memoization of functions from those types would require infinite storage. But Haskell is a lazy language, so the boundary between lazily evaluated (infinite) data structures and functions is fuzzy. This function vs. data duality explains the identification of Haskell’s function type with the categorical exponential object — which corresponds more to our idea of data.

Cartesian Closed Categories

Although I will continue using the category of sets as a model for types and functions, it’s worth mentioning that there is a larger family of categories that can be used for that purpose. These categories are called cartesian closed, and Set is just one example of such a category.

A cartesian closed category must contain:

- The terminal object,

- A product of any pair of objects, and

- An exponential for any pair of objects.

If you consider an exponential as an iterated product (possibly infinitely many times), then you can think of a cartesian closed category as one supporting products of an arbitrary arity. In particular, the terminal object can be thought of as a product of zero objects — or the zero-th power of an object.

What’s interesting about cartesian closed categories from the perspective of computer science is that they provide models for the simply typed lambda calculus, which forms the basis of all typed programming languages.

The terminal object and the product have their duals: the initial object and the coproduct. A cartesian closed category that also supports those two, and in which product can be distributed over coproduct

a × (b + c) = a × b + a × c (b + c) × a = b × a + c × a

is called a bicartesian closed category. We’ll see in the next section that bicartesian closed categories, of which Set is a prime example, have some interesting properties.

Exponentials and Algebraic Data Types

The interpretation of function types as exponentials fits very well into the scheme of algebraic data types. It turns out that all the basic identities from high-school algebra relating numbers zero and one, sums, products, and exponentials hold pretty much unchanged in any bicartesian closed category theory for, respectively, initial and final objects, coproducts, products, and exponentials. We don’t have the tools yet to prove them (such as adjunctions or the Yoneda lemma), but I’ll list them here nevertheless as a source of valuable intuitions.

Zeroth Power

a0 = 1

In the categorical interpretation, we replace 0 with the initial object, 1 with the final object, and equality with isomorphism. The exponential is the internal hom-object. This particular exponential represents the set of morphisms going from the initial object to an arbitrary object a. By the definition of the initial object, there is exactly one such morphism, so the hom-set C(0, a) is a singleton set. A singleton set is the terminal object in Set, so this identity trivially works in Set. What we are saying is that it works in any bicartesian closed category.

In Haskell, we replace 0 with Void; 1 with the unit type (); and the exponential with function type. The claim is that the set of functions from Void to any type a is equivalent to the unit type — which is a singleton. In other words, there is only one function Void->a. We’ve seen this function before: it’s called absurd.

This is a little bit tricky, for two reasons. One is that in Haskell we don’t really have uninhabited types — every type contains the “result of a never ending calculation,” or the bottom. The second reason is that all implementations of absurd are equivalent because, no matter what they do, nobody can ever execute them. There is no value that can be passed to absurd. (And if you manage to pass it a never ending calculation, it will never return!)

Powers of One

1a = 1

This identity, when interpreted in Set, restates the definition of the terminal object: There is a unique morphism from any object to the terminal object. In general, the internal hom-object from a to the terminal object is isomorphic to the terminal object itself.

In Haskell, there is only one function from any type a to unit. We’ve seen this function before — it’s called unit. You can also think of it as the function const partially applied to ().

First Power

a1 = a

This is a restatement of the observation that morphisms from the terminal object can be used to pick “elements” of the object a. The set of such morphisms is isomorphic to the object itself. In Set, and in Haskell, the isomorphism is between elements of the set a and functions that pick those elements, ()->a.

Exponentials of Sums

ab+c = ab × ac

Categorically, this says that the exponential from a coproduct of two objects is isomorphic to a product of two exponentials. In Haskell, this algebraic identity has a very practical, interpretation. It tells us that a function from a sum of two types is equivalent to a pair of functions from individual types. This is just the case analysis that we use when defining functions on sums. Instead of writing one function definition with a case statement, we usually split it into two (or more) functions dealing with each type constructor separately. For instance, take a function from the sum type (Either Int Double):

f :: Either Int Double -> String

It may be defined as a pair of functions from, respectively, Int and Double:

f (Left n) = if n < 0 then "Negative int" else "Positive int" f (Right x) = if x < 0.0 then "Negative double" else "Positive double"

Here, n is an Int and x is a Double.

Exponentials of Exponentials

(ab)c = ab×c

This is just a way of expressing currying purely in terms of exponential objects. A function returning a function is equivalent to a function from a product (a two-argument function).

Exponentials over Products

(a × b)c = ac × bc

In Haskell: A function returning a pair is equivalent to a pair of functions, each producing one element of the pair.

It’s pretty incredible how those simple high-school algebraic identities can be lifted to category theory and have practical application in functional programming.

Curry-Howard Isomorphism

I have already mentioned the correspondence between logic and algebraic data types. The Void type and the unit type () correspond to false and true. Product types and sum types correspond to logical conjunction ∧ (AND) and disjunction ⋁ (OR). In this scheme, the function type we have just defined corresponds to logical implication ⇒. In other words, the type a->b can be read as “if a then b.”

According to the Curry-Howard isomorphism, every type can be interpreted as a proposition — a statement or a judgment that may be true or false. Such a proposition is considered true if the type is inhabited and false if it isn’t. In particular, a logical implication is true if the function type corresponding to it is inhabited, which means that there exists a function of that type. An implementation of a function is therefore a proof of a theorem. Writing programs is equivalent to proving theorems. Let’s see a few examples.

Let’s take the function eval we have introduced in the definition of the function object. Its signature is:

eval :: ((a -> b), a) -> b

It takes a pair consisting of a function and its argument and produces a result of the appropriate type. It’s the Haskell implementation of the morphism:

eval :: (a⇒b) × a -> b

which defines the function type a⇒b (or the exponential object ba). Let’s translate this signature to a logical predicate using the Curry-Howard isomorphism:

((a ⇒ b) ∧ a) ⇒ b

Here’s how you can read this statement: If it’s true that b follows from a, and a is true, then b must be true. This makes perfect intuitive sense and has been known since antiquity as modus ponens. We can prove this theorem by implementing the function:

eval :: ((a -> b), a) -> b eval (f, x) = f x

If you give me a pair consisting of a function f taking a and returning b, and a concrete value x of type a, I can produce a concrete value of type b by simply applying the function f to x. By implementing this function I have just shown that the type ((a -> b), a) -> b is inhabited. Therefore modus ponens is true in our logic.

How about a predicate that is blatantly false? For instance: if a or b is true then a must be true.

a ⋁ b ⇒ a

This is obviously wrong because you can chose an a that is false and a b that is true, and that’s a counter-example.

Mapping this predicate into a function signature using the Curry-Howard isomorphism, we get:

Either a b -> a

Try as you may, you can’t implement this function — you can’t produce a value of type a if you are called with the Right value. (Remember, we are talking about pure functions.)

Finally, we come to the meaning of the absurd function:

absurd :: Void -> a

Considering that Void translates into false, we get:

false ⇒ a

Anything follows from falsehood (ex falso quodlibet). Here’s one possible proof (implementation) of this statement (function) in Haskell:

absurd (Void a) = absurd a

where Void is defined as:

newtype Void = Void Void

As always, the type Void is tricky. This definition makes it impossible to construct a value because in order to construct one, you would need to provide one. Therefore, the function absurd can never be called.

These are all interesting examples, but is there a practical side to Curry-Howard isomorphism? Probably not in everyday programming. But there are programming languages like Agda or Coq, which take advantage of the Curry-Howard isomorphism to prove theorems.

Computers are not only helping mathematicians do their work — they are revolutionizing the very foundations of mathematics. The latest hot research topic in that area is called Homotopy Type Theory, and is an outgrowth of type theory. It’s full of Booleans, integers, products and coproducts, function types, and so on. And, as if to dispel any doubts, the theory is being formulated in Coq and Agda. Computers are revolutionizing the world in more than one way.

Bibliography

- Ralph Hinze, Daniel W. H. James, Reason Isomorphically!. This paper contains proofs of all those high-school algebraic identities in category theory that I mentioned in this chapter.

Next: Natural Transformations.

Acknowledgments

I’d like to thank Gershom Bazerman for checking my math and logic, and André van Meulebrouck, who has been volunteering his editing help throughout this series of posts.

Follow @BartoszMilewski