I was overwhelmed by the positive response to my previous post, the Preface to Category Theory for Programmers. At the same time, it scared the heck out of me because I realized what high expectations people were placing in me. I’m afraid that no matter what I’ll write, a lot of readers will be disappointed. Some readers would like the book to be more practical, others more abstract. Some hate C++ and would like all examples in Haskell, others hate Haskell and demand examples in Java. And I know that the pace of exposition will be too slow for some and too fast for others. This will not be the perfect book. It will be a compromise. All I can hope is that I’ll be able to share some of my aha! moments with my readers. Let’s start with the basics.

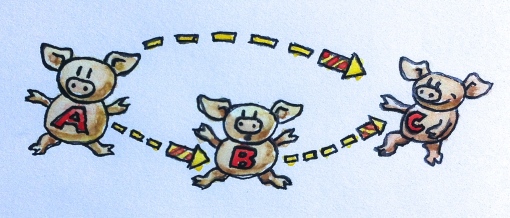

A category is an embarrassingly simple concept. A category consists of objects and arrows that go between them. That’s why categories are so easy to represent pictorially. An object can be drawn as a circle or a point, and an arrow… is an arrow. (Just for variety, I will occasionally draw objects as piggies and arrows as fireworks.) But the essence of a category is composition. Or, if you prefer, the essence of composition is a category. Arrows compose, so if you have an arrow from object A to object B, and another arrow from object B to object C, then there must be an arrow — their composition — that goes from A to C.

In a category, if there is an arrow going from A to B and an arrow going from B to C then there must also be a direct arrow from A to C that is their composition. This diagram is not a full category because it’s missing identity morphisms (see later).

Arrows as Functions

Is this already too much abstract nonsense? Do not despair. Let’s talk concretes. Think of arrows, which are also called morphisms, as functions. You have a function f that takes an argument of type A and returns a B. You have another function g that takes a B and returns a C. You can compose them by passing the result of f to g. You have just defined a new function that takes an A and returns a C.

In math, such composition is denoted by a small circle between functions: g∘f. Notice the right to left order of composition. For some people this is confusing. You may be familiar with the pipe notation in Unix, as in:

lsof | grep Chrome

or the chevron >> in F#, which both go from left to right. But in mathematics and in Haskell functions compose right to left. It helps if you read g∘f as “g after f.”

Let’s make this even more explicit by writing some C code. We have one function f that takes an argument of type A and returns a value of type B:

B f(A a);

and another:

C g(B b);

Their composition is:

C g_after_f(A a)

{

return g(f(a));

}

Here, again, you see right-to-left composition: g(f(a)); this time in C.

I wish I could tell you that there is a template in the C++ Standard Library that takes two functions and returns their composition, but there isn’t one. So let’s try some Haskell for a change. Here’s the declaration of a function from A to B:

f :: A -> B

Similarly:

g :: B -> C

Their composition is:

g . f

Once you see how simple things are in Haskell, the inability to express straightforward functional concepts in C++ is a little embarrassing. In fact, Haskell will let you use Unicode characters so you can write composition as:

g ∘ f

You can even use Unicode double colons and arrows:

f ∷ A → B

So here’s the first Haskell lesson: Double colon means “has the type of…” A function type is created by inserting an arrow between two types. You compose two functions by inserting a period between them (or a Unicode circle).

Properties of Composition

There are two extremely important properties that the composition in any category must satisfy.

1. Composition is associative. If you have three morphisms, f, g, and h, that can be composed (that is, their objects match end-to-end), you don’t need parentheses to compose them. In math notation this is expressed as:

h∘(g∘f) = (h∘g)∘f = h∘g∘f

In (pseudo) Haskell:

f :: A -> B g :: B -> C h :: C -> D h . (g . f) == (h . g) . f == h . g . f

(I said “pseudo,” because equality is not defined for functions.)

Associativity is pretty obvious when dealing with functions, but it may be not as obvious in other categories.

2. For every object A there is an arrow which is a unit of composition. This arrow loops from the object to itself. Being a unit of composition means that, when composed with any arrow that either starts at A or ends at A, respectively, it gives back the same arrow. The unit arrow for object A is called idA (identity on A). In math notation, if f goes from A to B then

f∘idA = f

and

idB∘f = f

When dealing with functions, the identity arrow is implemented as the identity function that just returns back its argument. The implementation is the same for every type, which means this function is universally polymorphic. In C++ we could define it as a template:

template<class T> T id(T x) { return x; }

Of course, in C++ nothing is that simple, because you have to take into account not only what you’re passing but also how (that is, by value, by reference, by const reference, by move, and so on).

In Haskell, the identity function is part of the standard library (called Prelude). Here’s its declaration and definition:

id :: a -> a id x = x

As you can see, polymorphic functions in Haskell are a piece of cake. In the declaration, you just replace the type with a type variable. Here’s the trick: names of concrete types always start with a capital letter, names of type variables start with a lowercase letter. So here a stands for all types.

Haskell function definitions consist of the name of the function followed by formal parameters — here just one, x. The body of the function follows the equal sign. This terseness is often shocking to newcomers but you will quickly see that it makes perfect sense. Function definition and function call are the bread and butter of functional programming so their syntax is reduced to the bare minimum. Not only are there no parentheses around the argument list but there are no commas between arguments (you’ll see that later, when we define functions of multiple arguments).

The body of a function is always an expression — there are no statements in functions. The result of a function is this expression — here, just x.

This concludes our second Haskell lesson.

The identity conditions can be written (again, in pseudo-Haskell) as:

f . id == f id . f == f

You might be asking yourself the question: Why would anyone bother with the identity function — a function that does nothing? Then again, why do we bother with the number zero? Zero is a symbol for nothing. Ancient Romans had a number system without a zero and they were able to build excellent roads and aqueducts, some of which survive to this day.

Neutral values like zero or id are extremely useful when working with symbolic variables. That’s why Romans were not very good at algebra, whereas the Arabs and the Persians, who were familiar with the concept of zero, were. So the identity function becomes very handy as an argument to, or a return from, a higher-order function. Higher order functions are what make symbolic manipulation of functions possible. They are the algebra of functions.

To summarize: A category consists of objects and arrows (morphisms). Arrows can be composed, and the composition is associative. Every object has an identity arrow that serves as a unit under composition.

Composition is the Essence of Programming

Functional programmers have a peculiar way of approaching problems. They start by asking very Zen-like questions. For instance, when designing an interactive program, they would ask: What is interaction? When implementing Conway’s Game of Life, they would probably ponder about the meaning of life. In this spirit, I’m going to ask: What is programming? At the most basic level, programming is about telling the computer what to do. “Take the contents of memory address x and add it to the contents of the register EAX.” But even when we program in assembly, the instructions we give the computer are an expression of something more meaningful. We are solving a non-trivial problem (if it were trivial, we wouldn’t need the help of the computer). And how do we solve problems? We decompose bigger problems into smaller problems. If the smaller problems are still too big, we decompose them further, and so on. Finally, we write code that solves all the small problems. And then comes the essence of programming: we compose those pieces of code to create solutions to larger problems. Decomposition wouldn’t make sense if we weren’t able to put the pieces back together.

This process of hierarchical decomposition and recomposition is not imposed on us by computers. It reflects the limitations of the human mind. Our brains can only deal with a small number of concepts at a time. One of the most cited papers in psychology, The Magical Number Seven, Plus or Minus Two, postulated that we can only keep 7 ± 2 “chunks” of information in our minds. The details of our understanding of the human short-term memory might be changing, but we know for sure that it’s limited. The bottom line is that we are unable to deal with the soup of objects or the spaghetti of code. We need structure not because well-structured programs are pleasant to look at, but because otherwise our brains can’t process them efficiently. We often describe some piece of code as elegant or beautiful, but what we really mean is that it’s easy to process by our limited human minds. Elegant code creates chunks that are just the right size and come in just the right number for our mental digestive system to assimilate them.

So what are the right chunks for the composition of programs? Their surface area has to increase slower than their volume. (I like this analogy because of the intuition that the surface area of a geometric object grows with the square of its size — slower than the volume, which grows with the cube of its size.) The surface area is the information we need in order to compose chunks. The volume is the information we need in order to implement them. The idea is that, once a chunk is implemented, we can forget about the details of its implementation and concentrate on how it interacts with other chunks. In object-oriented programming, the surface is the class declaration of the object, or its abstract interface. In functional programming, it’s the declaration of a function. (I’m simplifying things a bit, but that’s the gist of it.)

Category theory is extreme in the sense that it actively discourages us from looking inside the objects. An object in category theory is an abstract nebulous entity. All you can ever know about it is how it relates to other object — how it connects with them using arrows. This is how internet search engines rank web sites by analyzing incoming and outgoing links (except when they cheat). In object-oriented programming, an idealized object is only visible through its abstract interface (pure surface, no volume), with methods playing the role of arrows. The moment you have to dig into the implementation of the object in order to understand how to compose it with other objects, you’ve lost the advantages of your programming paradigm.

Challenges

- Implement, as best as you can, the identity function in your favorite language (or the second favorite, if your favorite language happens to be Haskell).

- Implement the composition function in your favorite language. It takes two functions as arguments and returns a function that is their composition.

- Write a program that tries to test that your composition function respects identity.

- Is the world-wide web a category in any sense? Are links morphisms?

- Is Facebook a category, with people as objects and friendships as morphisms?

- When is a directed graph a category?

Next: Types and Functions.

Follow @BartoszMilewski

November 4, 2014 at 10:49 am

My take on the first 2 challenges with C++14 lambdas and operator * for the composition: http://goo.gl/FvdOaS

Thank you for this promising post series, keep it going!

November 4, 2014 at 12:56 pm

“Is Facebook a category, with people as objects and friendships as morphisms?”

Is a ‘person’ considered a ‘friend’ to themselves?

If so, you have a nifty groupoid…since being a ‘friend’ is its own inverse morphism.

November 4, 2014 at 12:57 pm

“Is Facebook a category, with people as objects and friendships as morphisms?”

Is a ‘person’ considered a ‘friend’ to themselves?

If so, you have a nifty groupoid…since being a ‘friend’ is its own inverse morphism.

November 4, 2014 at 6:09 pm

Thanks for writing these posts! I’m enjoying them so far. Category theory’s one of those areas that I’ve been dimly aware of and interested in learning more about for a while, but haven’t really taken the time to investigate yet. (Ditto for Haskell, for that matter.)

November 5, 2014 at 12:40 pm

Thank you! As one who wanders around the foothills of CT, I appreciate well-done introductions. (And I am studying Scala, so I can scale higher)

November 5, 2014 at 1:15 pm

Love the analogy that the “surface area” of a chunk of code must be smaller than its volume. I love thinking about programming in new ways.

November 6, 2014 at 4:03 am

Enjoyed this post, and I’m looking forward to more. I’m totally lost at the last 3 Challenges though.

November 6, 2014 at 4:11 am

@mikefhay: These challenges are just food for thought. There is no right or wrong answer. Try to define the terms and see if they fit the definition of a category. If necessary, change your definitions. Play with various ideas.

November 6, 2014 at 8:00 am

Awesome explanation and analogies. Thanks!

November 17, 2014 at 1:25 am

Hi Dr. Bartosz,

Thanks for your nice sharing, but your explaination and examples are based on single variable functions. Can you please to give a more general explanation if we want to compose a multivariate function from several multivariate functions? Eg, given functions f(x), h(x), g(x1, x2), we want to compose a new function: w(x) = g(f(x), h(x)). How to describe them in graph, and what is the “suitable” syntax to express them in any functional language?

November 17, 2014 at 2:06 am

@humbleoh: I’ll talk about multi-argument functions later. The short explanation is that you treat a two argument function as a function on one argument that returns a new function of one argument (the remaining argument). That’s called currying.

In Haskell you just write it as

f x yand you can call it with one argument, sayf 41to get a function that expects one more argument. You can immediately call this function again,f 41 28, to get the final result. If you want, you can put parentheses around the first call,(f 41) 28, but it’s not necessary. The bottom line is that it looks and evaluates just like a regular function of two arguments, with the additional flexibility of allowing you to define partially applied functions likeg = f 41.November 20, 2014 at 1:21 am

[…] Category: The Essence of Composition | Bartosz Milewski’s Programming CafeType: article I was overwhelmed by the positive response to my previous post, the Preface to Category Theory for Programmers. At the same time, it scared the heck out of me because I realized what high expectations people were placing in me. I’m afraid that no matter what I’ll write, a lot of readers will be disappointed.… […]

November 24, 2014 at 8:10 am

One thing that would help me enormously would be to show some counterexamples – some things that resemble categories but which aren’t along with an explanation of why they don’t qualify.

The reason is that your initial description, “objects and arrows that go between them” sounds to me a lot like the definition of a directed graph. But does that mean all DGs are categories? Presumably not, but if you gave me a bunch of DGs I don’t think I could tell you which are categories and which are not – they’d all be a bunch of “objects and arrows that go between them”.

I’m trying to work out whether the composability you describe is a necessary qualifying characteristic – e.g. do the morphisms need to form their own transitive closure? If I have A, B, and C, with morphisms from A to B, and B to C but no morphism from A to C does that mean I’ve got a digraph that’s not a category?

From the text of this post, I think that’s the case (although in an earlier post you said morphisms “can be composed”, suggesting that composition is something you do to a morphism, rather than something that’s already ‘just there’ by virtue of something being a morphism of a category, so I’m not entirely sure).

You also talk about the importance of identity – each object in the category must have a morphism that is the identity under composition. This implies that any directed graph containing one or more objects that do not have arrows pointing to themselves is not a category.

But that would imply that the pigs-and-fireworks diagram at the top of this article isn’t a category. I am confused because it’s sort of implied that this diagram is an example of a category.

Had it not been for that diagram (and earlier posts suggesting that composition is something you do to a morphism, rather than something innately supported by the morphisms of any category) I would have concluded from the text that a category is a reflexive, transitive relation. From the pig diagram, I would conclude merely that it’s a transitive relation. At least one of these interpretations must be wrong, and possibly both are.

My provisional conclusion about the pig diagram (piggram? pigraph?) is that the identity morphisms are supposed to be implied – that we should assume the presence of an arrow from each element to itself because we’ve been told it’s a category, and that there’s some sort of convention of not having to make them all explicit.

That being so, I’d be left with the thought that a category is just a transitive, reflexive graph (in which reflexive arcs are omitted for clarity). But I suspect that’s probably also an oversimplification. In which case I’d find it really helpful to see an example of a reflexive, transitive graph (preferably with at least 3 nodes) that is not a category, and an explanation of why it isn’t.

November 24, 2014 at 12:29 pm

@idg10: I added a clarifying caption to the “piggram.” Does it answer you questions?

November 24, 2014 at 2:00 pm

Thanks – that answers almost all of them.

My remaining question is this: is there a distinction between a graph showing a reflexive, transitive relation, and one showing a category? (Is it possible to draw a diagram that represents one of these things without also being an illustration of the other?)

November 24, 2014 at 4:19 pm

@idg10: One example I gave is a category of all sets and functions between them. A graph is defined as a set of points and edges: the key word here being “set.” There is no set of all sets (such set would have to contain itself and that would lead to a paradox). But there is a category of all sets. So it’s a matter of dealing with bigger infinities.

November 24, 2014 at 10:49 pm

[…] This is part of the book Category Theory for Programmers. The previous instalment was Category: The Essence of Composition. […]

November 25, 2014 at 8:09 am

Ah! I was not thinking about infinite sets – that makes sense now. Thank you for your patient explanations!

November 25, 2014 at 1:25 pm

Hello,

Bartosz, I’m having technical difficulties with reading Unicode chars in code snippets (android 4.4, problem probably applies to many other phones) I know that there is a fallback font but somehow it does not work for code (mono spaced letters). Could you please for future wrie them using ansi letters? I like reading your posts as it’s definitely a lot I can learn, but for a Haskell novice like me, it’s not always obvious what to substitute the squares with…

November 25, 2014 at 1:59 pm

@PiotrWie: I only used Unicode in two code snippets, just to demonstrate their usage. Otherwise it’s all ASCII. But I might have to use Unicode occasionally in math, like the little circle for function composition or if I run out of symbols.

November 25, 2014 at 4:34 pm

@Bartosz, eureka! I’ve substituted stock droidsansfallback font with aerial Unicode from my PC and… It’s working 🙂 so, for anyone viewing your posts on android. To have code snippets displayed properly stock font needs to be changed. And great thanks for all your teaching posts… Piotr

BTW, phone has to be rooted for the procedure…

November 29, 2014 at 10:22 am

Thanks, Bartosz.

My take for id and compose in C++ is here: http://goo.gl/rvtzMV. The “auto id = …” line is to make GCC happy. Using id directly works in Clang, but not in GCC, for unknown reasons.

November 30, 2014 at 6:33 am

Hi Wu,

The lambda type is scoped anonymous. The compiler should not able to deduce the return type of the compose function.

December 1, 2014 at 7:28 am

Hi humbleoh,

Apparently the compiler can deduce the return type, as demonstrated by the short test program: http://goo.gl/wsWYrp.

Did I miss anything?

December 2, 2014 at 7:54 am

Hi Wu,

Sorry for my ignorance. I misunderstood the following:

The lambda type is unique anonymous, but it is not scoped.

And for your code, i have tried to compile it in my local machine using g++ 4.9.2. It runs well. It seems that there is a bug in g++ 4.9.0.

You may reach me at humbleoh (at) gmail dot com for further discussion, as our discussion may not be appropriate here. Thanks.

December 2, 2014 at 8:08 am

Hi Wu,

Sorry again. Your code may run well with g++ 4.9.0. I didnt run your code using g++ 4.9.0 in my local machine. Instead, I compiled it using the interative compiler as given by you. It was compiled successfully. Please compile your code and run the program to see if it gives the correct result.

December 8, 2014 at 7:22 pm

[…] Next: Category: The Essence of Composition. […]

December 16, 2014 at 7:41 pm

I guess I’ll take a shot at these questions here.

Here’s 1-3: https://gist.github.com/JonathanDCohen/79fab45340616347a199

4: No, I wouldn’t think so. Links I think are morphisms, but just because there is a link from page A to page B, and from page B to page C, doesn’t mean there’s a link from page A to page C, so the internet isn’t a category, at least in that sense.

5: Definitely not. My friends have a bunch of friends who aren’t friends with me.

February 12, 2015 at 3:18 am

I am going to copy and paste a fragment out of your beautifully-explained text up above just so I may ask for a clarification: “(I like this analogy because of the intuition that the surface area of a geometric object grows with the square of its size — slower than the volume, which grows with the cube of its size).” Do you mean to say SIDE or SIDES as opposed to the usage of the word SIZE in the quoted text? Just want to clarify, that’s all. Thanks in advance!

February 12, 2015 at 10:21 am

By “size” I mean “linear size”, like radius, or the distance between extremes. The thing you measure in meters. When you double the size of an object, you quadruple its surface area and increase its volume eightfold.

February 12, 2015 at 7:59 pm

I keep thinking about geometric figures when you mention Object and found the following definitions for the word SIDE – perhaps this might be of more help to clarify my question, and therefore think that the square of a side of a geometric object represents its Area (just like pi * R-squared represents the area of a circle, where R is its Radius):

b: a line or surface forming a border or face of an object

c: either surface of a thin object

d: a bounding line of a geometric figure

courtesy of Meriam-Webster: http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/side

Similarly, if we think of a Cube (instead of a Square), the cube of its SIDE yields the Volume of the Object Cube which is, in fact greater than the area of its corresponding Square Object (with the size of its SIDE equal to the size of its corresponding Cube SIDE).

Hence, my question in regards to your observation in the article: is it square of its SIZE and/or cube of its SIZE as opposed to using the word SIDE instead of SIZE? If so, it would all make sense since you take the square of the Square’s SIDE to find out its Area, and the cube of the Cube’s SIDE to find out its Volume, and it stands to reason that Area Of Square < Volume Of Cube – when the same SIDE length is employed for both the square and the cube.

I’m asking this so as to ensure I understand your analogy correctly. If what you mean by Linear Size is actually the same as saying SIDE (of any geometric figure), then I think I understand your analogy. If not, I am perhaps lacking in some notions in regards to Object Surfaces and Object Volumes, as depicted in your article.

February 12, 2015 at 9:02 pm

I’ve found a perfect explanation in wikipedia: Square Cube Law.

February 12, 2015 at 9:49 pm

Thank you and I quote from the Square Cube Law wiki: “For example, a cube with a side length of 1 meter has a surface area of 6 m2 and a volume of 1 m3. If the dimensions of the cube were multiplied by 2, its surface area would be multiplied by the square of 2 and become 24 m2. Its volume would be multiplied by the cube of 2 and become 8 m3. Thus the Square-cube law. This principle applies to all solids.”

Wikipedia uses the word SIDE without any problems, yet, your article mentions SIZE several times. While the Wikipedia article confirms that the term used should have been SIDE if you were referring to particular geometric figures, I now understand that you were meaning SIZE as a general term for the size of an object but it became confusing when you were squaring it, then cubing it – strictly algebraically speaking – in order to arrive at your Area versus Volume analogy.

So, having said that, not that I’m trying to be facetious, but tried very hard to understand your analogy, I think it would be useful to use the word SIDE as opposed to SIZE when you compute stuff algebraically so you may refer to geometric concepts such as Area, or Volume. I think the distinction is important and helpful for the rest of us.

I appreciate the 8 articles you’ve written – I am trying to dissect each and every one of them to see where I failed at OOP Programming. I hope that your website will clarify many of my misgivings about programming in general, and OOP or other Paradigms up-and-coming (such as Functional “Lambda” Programming) in particular.

Thank you again and hope to hear back from you on my possibly-upcoming questions pretty soon…

March 31, 2015 at 8:13 pm

Bartosz, you said that the identity morphism is a morphism from an object to itself. Does this mean that every function of type Int -> Int is an identity morphism?

March 31, 2015 at 8:54 pm

I think I should stress it that there may be many morphisms between two objects, and many morphisms from an object to itself. The example of the monoid in the next post illustrates this.

April 30, 2015 at 8:40 am

Python does a nice job of dealing with the challenge problems. For example, for composition:

def compose(f, g): return lambda *args, **kwargs: f(g(*args, **kwargs))

May 1, 2015 at 12:51 am

id function in c

#define id(x) (x)

May 1, 2015 at 5:34 am

@Jon

4: No, I wouldn’t think so. Links I think are morphisms, but just because there is a link from page A to page B, and from page B to page C, doesn’t mean there’s a link from page A to page C, so the internet isn’t a category, at least in that sense.

I think the web is a category. I can compose the links from A to B and B to C to get from A to C.

Or am I missing something?

Edit: changed morphism to category.

May 4, 2015 at 3:37 am

I’m probably the person who is the least familiar with the concepts you talk about, the little I understand about this comes from learning Haskell from books. I’m a sysadmin, programming is a skill I have only recently started to acquire.

Your blog is really interesting to read, Bartosz. Thank you for taking the effort to share it with the world.

My question is as follows. You said: “A category is an embarrassingly simple concept. A category consists of objects and arrows that go between them.”

Can you give me a little bit of background on why they chose the word “category”? In my limited brain, ‘category’ means group. Like with persons, if you want to collect data about them, you can use the category ‘age’, and ‘gender’ and so on.

Your examples work, but I am a person who thinks in words and understands concepts better via definitions. If you could explain this to me a little bit, it would make “category” less mysterious. Thank you! Mark

May 4, 2015 at 9:53 am

My understanding is that a category describes a whole category of systems or theories that share the same structure.

May 10, 2015 at 1:59 pm

Mine solution in C++: https://ideone.com/ZecFig

May 12, 2015 at 3:30 pm

Hi, how do I actually type your examples into Haskell?

I tried the obvious thing (Debian Jessie) :

john@dell-3537$ ghci

GHCi, version 7.6.3: http://www.haskell.org/ghc/ 😕 for help

Loading package ghc-prim … linking … done.

Loading package integer-gmp … linking … done.

Loading package base … linking … done.

Prelude> id :: a -> a

:2:1:

No instance for (Show (a0 -> a0)) arising from a use of `print’

Possible fix: add an instance declaration for (Show (a0 -> a0))

In a stmt of an interactive GHCi command: print it

Prelude> id x = x

:3:6: parse error on input `=’

Prelude>

May 12, 2015 at 4:15 pm

GHCi is an interactive shell. It tries to immediately print everything you type into it. But a function cannot be printed. So if you want to define a function interactively, you have to start the line with

let. Or define your functions in a text file with the extension.hs, for instance,main.hsand load them into GHCi using the:load main.hscommand.June 3, 2015 at 11:50 am

Great article! Thanks for your work! 🙂

June 17, 2015 at 3:31 pm

My take on challenges in scala:

This file contains bidirectional Unicode text that may be interpreted or compiled differently than what appears below. To review, open the file in an editor that reveals hidden Unicode characters.

Learn more about bidirectional Unicode characters

gistfile1.scala

hosted with ❤ by GitHub

July 21, 2015 at 8:51 pm

Thank you, Bartosz, for the wonderful work!

And my take in Ruby

This file contains bidirectional Unicode text that may be interpreted or compiled differently than what appears below. To review, open the file in an editor that reveals hidden Unicode characters.

Learn more about bidirectional Unicode characters

ruby_challenges.rb

hosted with ❤ by GitHub

October 13, 2015 at 1:08 am

Thanks for this series! But I really don’t like the surface area/volume analogy; you just can’t compare these two quantities, there is no order between them.

October 13, 2015 at 1:58 am

@Sebastian: You can’t compare these quantities, but you can compare the ratios. If you double the linear dimensions of a cube, its area quadruples, and its volume “octuples.” This means that the ratio of the volume of the bigger cube to the volume of the original cube is eight. Volume divided by volume is a dimensionless quantity.

This is why small mammals have higher metabolism than large mammals. They produce heat through their volume, but lose it by their area.

October 13, 2015 at 6:45 pm

Sure, but now you are using a completely different wording. From your article: “So what are the right chunks for the composition of programs? Their surface area has to be smaller than their volume.”

Maybe I should have said it differently though: I really don’t like how you explain your analogy.

October 13, 2015 at 10:07 pm

I don’t want to sound harsh btw. I just stumbled over the quoted sentence, that’s all.

October 14, 2015 at 1:53 am

I changed the wording. Is it better?

October 14, 2015 at 1:22 pm

Yep, it is 🙂

October 18, 2015 at 3:32 pm

Hello! I was re-reading this post and the answer about the need of the identity morphisms appeared not satisfiable for me. I guess it could be interesting to include the explanations indicated here by prof. Baez and mr. Zhang: https://www.quora.com/Category-Theory/Whats-the-purpose-of-identity-morphisms

If shortly: we need them to induce more rich isomorphisms structure in the category. And of course to get the definition of iso. Hope that this will be interesting piece of info for you and all, who is reading this blog.

October 18, 2015 at 4:54 pm

@karkunow: I was only explaing why the identity function is a useful concept in programming. Notice that quora answers, which deal with the more general question of identity morphisms in an arbitrary category, are relatively advanced compared to the material in the introductory section of my book. They talk about the importance of isomorphisms and the Yoneda lemma (I haven’t introduced isomorphisms at this point yet, and the Yoneda lemma comes much later).

I think the main reason for including identity morphisms in the definition of a category is that without them the theory wouldn’t be rich enough to be interesting. The definition should be as simple as possible, but not simpler than that. It’s a very pragmatic decision.

October 19, 2015 at 2:46 am

@Bartosz, understood, thanks! Just didn’t noticed that I was asking myself about those in the more general scope 🙂

October 25, 2015 at 1:25 pm

I appreciate the pace of your explanations, not in a hurry, careful to progress from one concept to the next, patient. As someone who’s become fatigued by IT fadism of late, the mathematical basis for functional programming is both stimulating and refreshing.

December 21, 2015 at 9:33 pm

I liked your question “Is the world-wide web a category?” a lot, so here is my answer: it is a quiver (directed multigraph with self-edges allowed). A category structure arises naturally from it by considering paths as morphisms (free category).

December 26, 2015 at 10:13 am

Great article! I will try out the questions.

Suppose we take the definition that morphisms has to be composable and category has to have identity, then I think WWW is a category if we think of “being able to reach a page” as arrow. To reach the same page, you just click no link, and you are on the same page, which is the identity arrow. Suppose there are links to go from A to B, and links to go from B to C. Then we can obviously go from A to C.

On the other hand, FB is not a category if we think of “being a friend of” as arrow, since I need not be a friend of myself, thus missing the identity arrow.

December 26, 2015 at 11:38 am

@Alex: Notice that it all depends on the definition of morphism. In the WWW case you defined it as “being able to reach a page.” In the Facebook case, you have some freedom on defining “being a friend of” as, for instance, being able to see their private data. In that case you are your own friend. What breaks down in that case is composability. A friend of my friend is not necessarily my friend. On the other hand, if you define a morphism as being able to reach somebody by going through public lists of friends, their friends, and so on; you will probably end with everybody on the internet being your friend. This way Kevin Bacon’s your friend. Unless there are some cliques with no external friends.

Thinking about these things improves your creativity.

January 12, 2016 at 4:26 am

Thanks for this awesome post

Here is my attempt for the challenges in Javascript: https://jsfiddle.net/nd18pbyu/

February 4, 2016 at 2:26 am

Here’s my JuliaLang:

Interestingly, though, I had some trouble trying to use ∘ with anonymous functions without wrapping them in parens (https://github.com/JuliaLang/julia/issues/14933).

April 4, 2016 at 3:46 am

[…] lecture greatly increased my interest in functional parsers. Functional parsers are about the essence of (functional) programming because they are about the concept of composition which is one of the core concepts of programming […]

November 4, 2016 at 3:34 am

In F# (trivial):

let (<.>) (g : ‘b -> ‘c) (f : ‘a -> ‘b) = f >> g

let test =

let a = 1

let f = (+) 1

let g = string

let eqs c = g(f(a)) = c

a |> (id <.> g <.> f) |> eqs &&

a |> (g <.> id <.> f) |> eqs &&

a |> (g <.> f <.> id) |> eqs

val ( <.> ) : g:(‘b -> ‘c) -> f:(‘a -> ‘b) -> (‘a -> ‘c)

val test : bool = true

December 24, 2016 at 10:50 pm

This is brilliant. I read through this step by step and careful approach of CT an I want to cry :*****

January 9, 2017 at 11:58 am

Good intro.

August 31, 2017 at 11:05 am

“The moment you have to dig into the implementation of the object in order to understand how to compose it with other objects, you’ve lost the advantages of your programming paradigm.”

What does it mean to dig? Dig how? Dig when? Dig what? Dig why?

What advantages?

What is composition?

What is object?

What is paradigm?

What is losing?

What is understanding?

What I suggest here is that this sentence is meaningless. Or not?

August 31, 2017 at 11:15 am

PS: I kinda like this sentence but I would like to see precisely defined what it means because this idea might have some potential but in its current form it is not more than Deepak Chopra quantum mambo jambo:

The energy of the life force in the universe manifests itself using infinite vibrations of the highest resonance in the vortex chakra by opening up new dimensions.

August 31, 2017 at 12:17 pm

PS2: In higher dimensions the volume is in the surface (see statistical physics undergrad courses, microcanonical distribution).

August 31, 2017 at 12:33 pm

“The surface area is the information we need in order to compose chunks. The volume is the information we need in order to implement them. The idea is that, once a chunk is implemented, we can forget about the details of its implementation and concentrate on how it interacts with other chunks. ”

What is information? In what sense? Kolmogorov entropy? Bits?

Let’s take functions for example:

surface = what does it supposed to do ?

volume = what does it do (on the machine / implementation level) in order to do what it supposed to do ?

The information content of the two is the same, they are just described in different languages.

Human language (surface) vs programming language (volume).

So a better analogy would be : surface=human friendly description vs volume=computer friendly description, this is what AI brings now closer to eachother. How information (=algorithms/rules) is represented.

September 3, 2017 at 10:25 am

The surface is the interface. That’s the part you have to know in order to use it. Unfortunately, in weakly-typed languages, the interface doesn’t give you much information, so you have to rely more on documentation or, in the worst case, you have to study the implementation.

September 5, 2017 at 11:07 am

I’m starting to think I’m too dumb to understand anything beyond kindergarten math. For example, I’m simply unable to understand the following:

“For every object A there is an arrow which is a unit of composition. This arrow loops from the object to itself. Being a unit of composition means that, when composed with any arrow that either starts at A or ends at A, respectively, it gives back the same arrow. The unit arrow for object A is called idA (identity on A).”

September 5, 2017 at 12:38 pm

I must confess that I understand a statement like this only because I’ve seen a diagram of it. You need a pencil and a piece of paper to visualize it.

September 5, 2017 at 12:44 pm

Roni, it is easy enough – just try to draw it as Bartosz recommends.

In plain English the notion of the category can be explained as

it is just a bunch of dots connected with arrows in a specific way (to meet axioms). If you you will take some time to think about it you will see that category is simply a bunch of triangles and loops (maybe very very big infinite set of those).

November 4, 2017 at 10:38 pm

Bartosz Milewski, Here’s my attempt at 1, 2, and 3: https://gist.github.com/addison-grant/f707fb2abf7ff9127934c13f86b05511. Is that along the lines of what you were thinking?

November 5, 2017 at 5:26 am

Some of the intro examples of category theory conc. relations remind me of Prolog programming language intro examples (e.g. regarding family trees). Does it mean Prolog is suited to experiment?

November 5, 2017 at 6:54 am

@Addison: Looks ok, but strictly speaking, since JS has not types, it’s not a full-blown category but rather a monoid.

May 19, 2018 at 2:58 am

In order to get a good grasp of what categories are, can you give some examples of sets and arrows that are not categories? In particular, it would be interesting to see examples that violate the associativeness condition.

May 19, 2018 at 11:16 am

For instance, functions that operate on floating-point numbers are not associative because of rounding errors.

October 17, 2018 at 1:06 pm

Hi Bartosz, thank you for taking the time to write this book, I find myself returning to it often, starting again from the beginning and getting a bit further each time

Something I realised I didn’t quite understand here upon the recent re-read which I think is probably quite fundamental to the rest of the book is understanding the following:

If we have morphism

f :: a -> bandg :: b -> cdoesn’t that necessarily imply that we have a morphismh :: a -> c?I should elaborate to try and make it clear why this is confusing me…

I suppose I’m not understanding how that cannot be the case. In the FB example question, we can surely always compose the relations between persons A to B, and B to C to show there is a relation between A and C

Is my confusion arising because of the interpretation of what a morphism between objects is supposed to mean?

I was thinking of them as transformations between objects, such as object A becomes object B after transformation

f, but that seems at odds with what others in the comments here discuss with the FB questionI suppose then that I’m thinking of this as travelling on a directed graph, but it’s not clear to me how else I am supposed to be thinking of this.

October 17, 2018 at 1:40 pm

No, you’re not confused. It’s part of the definition of a category that for any pair of composable morphism (like your f ang g) there must exist their composition, which is a morphism from a to c.

October 18, 2018 at 4:16 pm

Hi Bartosz,

Thank you for taking the time, and replying so promptly!

You have cleared it up for me very succinctly I think.

fandgare composable in my view of what the morphisms were, but other posters considered ‘friendship’ a non-composable relation I think.As a side note I went through a small rabbithole of papers curious as to the relation with directed graphs and categories. It seems surprisingly accessible to me alongside the later parts of your book, particularly related to free objects.

Thanks again, and best regards

May 3, 2019 at 4:59 pm

OK, I’ve spent way too much time thinking about whether Facebook is a category or not. I believe it is, especially if you think about it in terms of how it works. It’s got objects and associations (e.g., GraphQL models it exactly like that), so associated-with is the morphism, but there are many different kinds – is that OK? I’m not sure, based on how the question is posed.

I then started wondering whether it’s also a monoid category if the single object is the set of all people, and the morphisms are associations, still. I don’t know what unit would be.

May 7, 2019 at 5:35 pm

How can one tell if the morphisms of a category is representing functions or not if according to definition of category all we need to define a category is basically its topology (structure), that is objects and the arrows between them?

June 16, 2019 at 4:05 pm

[…] 原文见 https://bartoszmilewski.com/20… […]

June 23, 2019 at 12:29 am

Wow, this is really well written! Here’s my take on the first three challenges.

https://github.com/aneeshdurg/category_theory_for_programmers/blob/master/01/prog.rs

October 4, 2019 at 1:04 pm

Hi Bartosz. I get that composition of functions like f ( g (2) ) becomes a diagram as follow:

o —-> o —-> o

g f

But what about f ( g ) ? Is it as follow?

o —–> o

|

f |

—>o

That means the input to f is itself a morphism?

October 4, 2019 at 2:23 pm

The second example is not composition. It’s just a higher order function.

October 4, 2019 at 3:15 pm

But isn’t f ( g ) itself composition of f and g?!! f o g? If not then what forces the distinction between composition of functions and application of a function to another one which you called higher order function?

October 4, 2019 at 4:15 pm

A function that takes another function as an argument is free to do anything with that function. For instance, it may ignore it. Or it may call it several times with different arguments. Composition is very specific: you call the inner function once, pass the result to the outer function, and return its result.

October 4, 2019 at 4:43 pm

Got it. Thanks a lot.

November 8, 2019 at 2:48 am

Awesome article teacher

April 21, 2020 at 3:44 pm

solutions to challenges in TypeScript (JavaScript with types)

https://www.typescriptlang.org/v2/en/play#code/C4TwDgpgBAkgJhAdsAlqAPAFQHxQLxQAUA9gFxSYCU+umAUHaJFAGKLowA0UA8rgYQCGAJwDm5GNTy4eDJtADCxALZhiAZwjoAgtwBC3BfyIAzROTY792bmYBMF9gahGpuIWPLa3LhgGMAG0F1dSgAEUFgQSxcAG86KESoFARkNBAJVNQMHHwiYh9iBiSoPxU1TXIlVQ0tTE563IEzAEZbRDsfQgAPH1bCex7KSjoAX39iRHVgKDhIwTzECAB3cPn0RABXZQAjCGFsQhG6MqniAIgAOgDiUUI5qMuUpGyQQgAWKTwCT4mzi+ut3u80uZRqmh6NCg3SgACooHZuDDpNCoABqKAtS4AVkohAAzMM-upzlcbncEkkHoJQeVapCUTD4YjZiDnmlQHjcfhvqzHmCKhBgY92a8kVCmQiuSMRkA

May 18, 2020 at 3:46 pm

you wrote: It helps if you read g∘f as “g after f.”

It seems that it helps (me more) if [I] read g∘f as “g of f.”; which is supported by the example: g_of_f (A a) { return g(f(a)) }. Consider it. Say it to yourself – it makes a difference.

December 7, 2020 at 4:43 pm

Dear Bartosz, I am confused by the identity morphisms the way they are mapped to programming. If I understood correctly, with strongly typed languages, we need to consider types as objects of the category and Morphisms between A and B as a function that takes an argument of Type A and returning a value of Type B. So Int -> Float is one arrow/morphism and various implementations of that function like 5 -> 1.1 or 6 -> 2.1 etc are not really arrows in this category. And Identity morphism of type A is a morphism that takes an argument of Type A and return a value of Type A. When you described identity morphism, your declaration is consistent with the above Int -> Int but when you implemented it you were returning the same argument value as the input. That is you implemented it x -> x which is not an arrow, going by the above.

Why is 5 -> 5 an identity morphism but not 5 -> 6 not an identity morphism in the category of types? That is my confusion. I am probably wrong in my understanding of how identity morphisms are defined. Thank you.

December 7, 2020 at 5:55 pm

5->1.2 is not a function. A function must be defined for all integers, not just 5. Identity is defined by its composition with other morphisms.

December 8, 2020 at 6:31 pm

OK, I get that now. The explanation of my confusion is not correct.

I am still bothered that something does not add up for me which means I feel I do not understand properly. Let me try it this way.

In the category of types an Identity Morphism is one that goes from a type to itself (e.g Int -> Int ). Let us call that IdInt. It does not say anything the internal logic of that function. It can take a 4 and return a 4, it can take a 3 and return a 3 and equally validly it can take 5 and return a 6, fully satisfying the type signature.

Let us say there is another morphism g that goes from Int -> Float

now the composition g . IdInt = g.

That is you can freely replace g.IdInt with g without losing anything.

If IdInt as a programming language function is implemented where it returns the same value as the input, then I see that g.IdInt is same as g.

so if IdInt is implemented where for input 3 it returns 3 then

it is true that g. idInt 3 is same as g 3

But if IdInt fully satisfying its type signature Int -> Int takes a value of 5 and returns a value of 6. then g.IdInt 5 is not the same as g 5

It almost looks like types are not the objects as per category theory when it comes to programming languages.

Where is my disconnect?

December 8, 2020 at 7:01 pm

You just showed that the function that takes 5 and returns 6 is not an identity morphism. It’s just some other random morphism from Int to Int.

December 8, 2020 at 7:28 pm

OK. That makes sense. Thanks.

I do know that in the category of sets, objects are sets, morphisms are set functions and identity morphism is a set function from a set to itself where ‘each individual element of the set maps to itself’.

Do the category of Types in programming languages and Category of Sets in Mathematics are the same category then? ( leaving aside the computability aspects )

December 8, 2020 at 7:31 pm

Ah..I just started reading the next chapter where you talk about Types and Sets. If the above is answered there, I am cool.

July 6, 2021 at 5:27 pm

Wondering if anyone else is thinking in terms of types for questions 3 and 4, and also if this is they right way of approaching what category theory is all about.

In the examples,

f :: a -> bis a function that outputs a value of typebbased on some quality of the argument which is of typea. But then the identity functionid: a -> ais not just any function that takes argument of typeaand returns any value of typea, but only itself. For instance,(+) :: Num a => a -> ais not an identity function, but if we were to draw the “piggram” in terms of types, the arrow would point back to pig A.So drawing the piggram in terms of types, a web link leading to another web link is the “Web” object pointing back to itself. However, if the piggrams were in terms of web page instances, outbound links could be drawn as

a -> bwhere both objectsaandbare Web page instances. And thinking about web page links on mobile devices, a link that goes froma -> bcould actually bea -> Either<b, c>wherebis the web page instance andcthe app version. (Many webpages nowadays either open the app if the phone has the app installed or just go to the web page otherwise.)I guess I’m a little confused how to wrap my head around the concept of category, and whether this is the correct way to go about it.

July 28, 2021 at 1:02 pm

[…] of one function fits as the input for another, you can sequentially compose them. Always. There are deep mathematical reasons for that, but suffice it to say that composition is ingrained into the fabric that pure functions […]

May 1, 2022 at 2:25 am

Hello, this is my response for the challenge in typescript

https://stackblitz.com/edit/typescript-z7xb11

July 21, 2022 at 2:18 am

To test for identity, it was easier for me to comprehend by actually breaking that law.

Javascript

const identity = a => a const Functor = (a) => ({ value: a, map(fn) { // transforming the value first with // Number breaks the identity law return Functor(fn(Number(this.value))) } }) const a = Functor('20') const b = a.map(identity) console.log(a.value, b.value, a.value === b.value) // '20', 20, false