“Data structures in functional languages are immutable.”

What?! How can you write programs if you can’t mutate data? To an imperative programmer this sounds like anathema. “Are you telling me that I can’t change a value stored in a vector, delete a node in a tree, or push an element on a stack?” Well, yes and no. It’s all a matter of interpretation. When you give me a list and I give you back the same list with one more element, have I modified it or have I constructed a brand new list with the same elements plus one more?

Why would you care? Actually, you might care if you are still holding on to your original list. Has that list changed? In a functional language, the original data structure will remain unmodified! The version from before the modification persists — hence such data structures are called persistent (it has nothing to do with being storable on disk).

In this post I will discuss the following aspects of persistent data structures:

- They are immutable, therefore

- They are easier to reason about and maintain

- They are thread-safe

- They can be implemented efficiently

- They require some type of resource management to “garbage collect” them.

I will illustrate these aspects on a simple example of a persistent linked list implemented in C++.

Motivation

There is a wealth of persistent data structures in functional languages, a lot of them based on the seminal book by Chris Okasaki, Purely Functional Data Structures (based on his thesis, which is available online). Unfortunately, persistent data structures haven’t found their way into imperative programming yet. In this series of blog posts I’ll try to provide the motivation for using functional data structures in imperative languages and start translating some of them into C++. I believe that persistent data structures should be part of every C++ programmer’s toolbox, especially one interested in concurrency and parallelism.

Persistence and Immutability

What’s the advantage of persistent data structures? For one, they behave as if they were immutable, yet you can modify them. The trick is that the modifications never spread to the aliases of the data structure — nobody else can observe them other that the mutator itself. This way you avoid any implicit long-distance couplings. This is important for program maintenance — you know that your bug fixes and feature tweaks will remain localized, and you don’t have to worry about breaking remote parts of the program that happen to have access to the same data structure.

There is another crucial advantage of immutable data structures — they are thread safe! You can’t have a data race on a structure that is read-only. Since copies of a persistent data structure are immutable, you don’t need to synchronize access to them. (This is, by the way, why concurrent programming is much easier in functional languages.)

Persistence and Multithreading

So if you want just one reason to use persistent data structures — it’s multithreading. A lot of conventional wisdom about performance is void in the face of multithreading. Concurrent and parallel programming introduces new performance criteria. It forces you to balance the cost of accessing data structures against the cost of synchronization.

Synchronization is hard to figure out correctly in the first place and is fraught with such dangers as data races, deadlocks, livelocks, inversions of control, etc. But even if your synchronization is correct, it may easily kill your performance. Locks in the wrong places can be expensive. You might be tempted to use a traditional mutable data structure like a vector or a tree under a single lock, but that creates a bottleneck for other threads. Or you might be tempted to handcraft your own fine granularity locking schemes; which is tantamount to designing your own data structures, whose correctness and performance characteristics are very hard to estimate. Even the lock-free data structures of proven correctness can incur substantial synchronization penalty by spinning on atomic variables (more about it later).

The fastest synchronization is no synchronization at all. That’s why the holy grail of parallelism is either not to share, or share only immutable data structures. Persistent data structures offer a special kind of mutability without the need for synchronization. You are free to share these data structures without synchronization because they never change under you. Mutation is accomplished by constructing a new object.

Persistence and Performance

So what’s the catch? You guessed it — performance! A naive implementation of a persistent data structure would require a lot of copying — the smallest modification would produce a new copy of the whole data structure. Fortunately, this is not necessary, and most implementations try to minimize copying by essentially storing only the “deltas.” Half of this blog will be about performance analysis and showing that you can have your cake and eat it too.

Every data structure has unique performance characteristics. If you judge a C++ vector by the performance of indexed access, its performance is excellent: it’s O(1) — constant time. But if you judge it by the performance of insert, which is O(N) — linear time — it’s pretty bad. Similarly, persistent data structures have their good sides and bad sides. Appending to the end of a persistent singly-linked list, for instance, is O(N), but push and pop from the front are a comfortable O(1).

Most importantly, major work has been done designing efficient persistent data structures. In many cases they closely match the performance of mutable data structures, or are within a logarithm from them.

Persistent List: First Cut

Before I get to more advanced data structures in the future installments of this blog, I’d like to start with the simplest of all: singly-linked list. Because it’s so simple, it will be easy to demonstrate the craft behind efficient implementation of persistency.

We all know how to implement a singly linked list in C++. Let’s take a slightly different approach here and define it abstractly first. Here’s the definition:

A list of T is either empty or consists of an element of type T followed by a list of T.

This definition translates directly into a generic data structure with two constructors, one for the empty list and another taking the value/list (head/tail) pair:

template<class T>

class List {

public:

List();

List(T val, List tail);

...

};

Here’s the trick: Since we are going to make all Lists immutable, we can guarantee that the second argument to the second constructor (marked in red) is forever frozen. Therefore we don’t have to deep-copy it, we can just store a reference to it inside the list. This way we can implement this constructor to be O(1), both in time and space. It also means that those List modifications that involve only the head of the list will have constant cost — because they can all share the same tail. This is very important, because the naive copying implementation would require O(N) time. You’ll see the same pattern in other persistent data structures: they are constructed from big immutable chunks that can be safely aliased rather than copied. Of course this brings the problem of being able to collect the no-longer-referenced tails — I’ll talk about it later.

Another important consequence of immutability is that there are two kinds of Lists: empty and non-empty. A List that was created empty will always remain empty. So the most important question about a list will be whether it’s empty or not. Something in the implementation of the list must store this information. We could, for instance, have a Boolean data member, _isEmpty, but that’s not what we do in C++. For better or worse we use this “clever” trick called the null pointer. So a List is really a pointer that can either be null or point to the first element of the list. That’s why there is no overhead in passing a list by value — we’re just copying a single pointer.

Is it a shallow or a deep copy? Technically it’s shallow, but because the List is (deeply) immutable, there is no observable difference.

Here’s the code that reflects the discussion so far:

template<class T>

class List

{

struct Item;

public:

List() : _head(nullptr) {}

List(T v, List tail) : _head(new Item(v, tail._head)) {}

bool isEmpty() const { return !_head; }

private:

// may be null

Item const * _head;

};

The Item contains the value, _val and a pointer _next to the (constant) Item (which may be shared between many lists):

struct Item

{

Item(T v, Item const * tail) : _val(v), _next(tail) {}

T _val;

Item const * _next;

};

The fact that items are (deeply) immutable can’t be expressed in the C++ type system, so we use (shallow) constness and recursive reasoning to enforce it.

In a functional language, once you’ve defined your constructors, you can automatically use them for pattern matching in order to “deconstruct” objects. For instance, an empty list would match the empty list pattern/constructor and a non-empty list would match the (head, tail) pattern/constructor (often called “cons”, after Lisp). Instead, in C++ we have to define accessors like front, which returns the head of the list, and pop_front, which returns the tail:

T front() const

{

assert(!isEmpty());

return _head->_val;

}

List pop_front() const

{

assert(!isEmpty());

return List(_head->_next);

}

In the implementation of pop_front I used an additional private constructor:

explicit List (Item const * items) : _head(items) {}

Notice the assertions: You are not supposed to call front or pop_front on an empty list. Make sure you always check isEmpty before you call them. Admittedly, this kind of interface exposes the programmer to potential bugs (forgetting to check for an empty list) — something that the pattern-matching approach of functional languages mitigates to a large extent. You could make these two methods safer in C++ by using boost optional, but not without some awkwardness and performance overhead.

We have defined five primitives: two constructors plus isEmpty, front, and pop_front that completely describe a persistent list and are all of order O(1). Everything else can be implemented using those five. For instance, we may add a helper method push_front:

List push_front(T v) const {

return List(v, *this);

}

Notice that push_front does not modify the list — it returns a new list with the new element at its head. Because of the implicit sharing of the tail, push_front is executed in O(1) time and takes O(1) space.

The list is essentially a LIFO stack and its asymptotic behavior is the same as that of the std::vector implementation of stack (without the random access, and with front and back inverted). There is an additional constant cost of allocating Items (and deallocating them, as we’ll see soon) both in terms of time and space. In return we are gaining multithreaded performance by avoiding the the need to lock our immutable data structures.

I’m not going to argue whether this tradeoff is always positive in the case of simple lists. Remember, I used lists to demonstrate the principles behind persistent data structures in the simplest setting. In the next installment though, I’m going to make a stronger case for tree-based data structures.

Reference Counting

If we could use garbage collection in C++ (and there are plans to add it to the Standard) we’d be done with the List, at least in the case of no hard resources (the ones that require finalization). As it is, we better come up with the scheme for releasing both memory and hard resources owned by lists. Since persistent data structures use sharing in their implementation, the simplest thing to do is to replace naked pointers with shared pointers.

Let’s start with the pointer to the head of the list:

std::shared_ptr<const Item> _head;

We no longer need to initialize _head to nullptr in the empty list constructor because shared_ptr does it for us. We need, however, to construct a new shared_ptr when creating a list form a head and a tail:

List() {}

List(T v, List const & tail)

: _head(std::make_shared<Item>(v, tail._head)) {}

Item itself needs a shared_ptr as _next:

struct Item

{

Item(T v, std::shared_ptr<const Item> const & tail)

: _val(v), _next(tail) {}

T _val;

std::shared_ptr<const Item> _next;

};

Surprisingly, these are the only changes we have to make. Everything else just works. Every time a shared_ptr is copied, as in the constructors of List and Item, a reference count is automatically increased. Every time a List goes out of scope, the destructor of _head decrements the reference count of the first Item of the list. If that item is not shared, it is deleted, which decreases the reference count of the next Item, and so on.

Let’s talk about performance again, because now we have to deal with memory management. Reference counting doesn’t come for free. First, a standard implementation of shared_ptr consists of two pointers — one pointing to data, the other to the reference counter (this is why I’m now passing List by const reference rather than by value — although it’s not clear if this makes much difference).

Notice that I was careful to always do Item allocations using make_shared, rather than allocating data using new and then turning it into a shared_ptr. This way the counter is allocated in the same memory block as the Item. This not only avoids the overhead of a separate call to new for the (shared) counter, but also helps locality of reference.

Then there is the issue of accessing the counter. Notice that the counter is only accessed when an Item is constructed or destroyed, and not, for instance, when the list is traversed. So that’s good. What’s not good is that, in a multithreaded environment, counter access requires synchronization. Granted, this is usually the lock-free kind of synchronization provided by shared_ptr, but it’s still there.

So my original claim that persistent data structures didn’t require synchronization was not exactly correct in a non-garbage-collected environment. The problem is somewhat mitigated by the fact that this synchronization happens only during construction and destruction, which are already heavy duty allocator operations with their own synchronization needs.

The cost of synchronization varies depending on how much contention there is. If there are only a few threads modifying a shared list, collisions are rare and the cost of a counter update is just one CAS (Compare And Swap) or an equivalent atomic operation. The overhead is different on different processor, but the important observation is that it’s the same overhead as in an efficient implementation of a mutex in the absence of contention (the so called thin locks or futexes require just one CAS to enter the critical section — see my blog about thin locks).

At high contention, when there are a lot of collisions, the reference count synchronization degenerates to a spin lock. (A mutex, on the other hand, would fall back on the operating system, since it must enqueue blocked threads). This high contention regime, however, is unlikely in the normal usage of persistent data structures.

A little digression about memory management is in order. Allocating Items from a garbage-collected heap would likely be more efficient, because then persistent objects would really require zero synchronization, especially if we had separate per-processor heaps. It’s been known for some time that the tradeoff between automated garbage collection (GC) and reference counting (RC) is far from obvious. David Bacon et. al. showed that, rather than there being one most efficient approach, there is a whole spectrum of solutions between GC and RC, each with their own performance tradeoffs.

There is a popular belief that GC always leads to long unexpected pauses in the execution of the program. This used to be true in the old times, but now we have incremental concurrent garbage collectors that either never “stop the world” or stop it for short bounded periods of time (just do the internet search for “parallel incremental garbage collection”). On the other hand, manual memory management a la C++ has latency problems of its own. Data structures that use bulk allocation, like vectors, have to occasionally double their size and copy all elements. In a multithreaded environment, this not only blocks the current thread from making progress but, if the vector is shared, may block other threads as well.

The use of shared_ptr in the implementation of containers may also result in arbitrarily long and quite unpredictable slowdowns. A destruction of a single shared_ptr might occasionally lead to a cascade of dereferences that deallocate large portions of a data structure, which may in turn trigger a bout of free list compactions within the heap (this is more evident in tree-like, branching, data structures). It’s important to keep these facts in mind when talking about performance tradeoffs, and use actual timings in choosing implementations.

List Functions

Since, as I said, a persistent list is immutable, we obviously cannot perform destructive operations on it. If we want to increment each element of a list of integers, for instance, we have to create a new list (which, by the way, doesn’t change the asymptotic behavior of such an operation). In functional languages such bulk operations are normally implemented using recursion.

You don’t see much recursion in C++ because of one problem: C++ doesn’t implement tail recursion optimization. In any functional language worth its salt, a recursive function that calls itself in its final step is automatically replaced by a loop. In C++, recursion consumes stack and may lead to stack overflow. So it’s the lack of guaranteed tail recursion optimization that is at the root of C++ programmers’ aversion to recursion. Of course, there are also algorithms that cannot be made tail recursive, like tree traversals, which are nevertheless implemented using recursion even in C++. One can make an argument that (balanced) tree algorithms will only use O(log(N)) amounts of stack, thus mitigating the danger of stack overflow.

List algorithms may be implemented either using recursion or loops and iterators. I’ll leave the implementation of iterators for a persistent list to the reader — notice that only a const forward iterator or an output iterator make sense in this case. Instead I’ll show you a few examples of recursive algorithms. They can all be rewritten using loops and iterators, but it’s interesting to see them in the purest form.

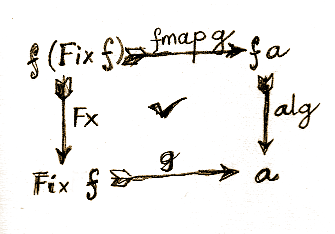

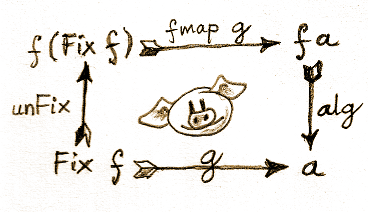

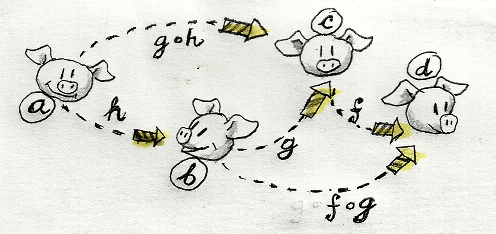

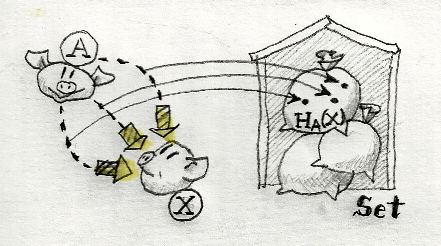

The example of incrementing each element of a list is a special case of a more general algorithm of applying a function to all elements of a list. This algorithm is usually called fmap and can be generalized to a large variety of data structures. Those parameterized data structures that support fmap are called functors (not to be confused with the common C++ misnomer for a function object). Here’s fmap for our persistent list:

template<class U, class T, class F>

List<U> fmap(F f, List<T> lst)

{

static_assert(std::is_convertible<F, std::function<U(T)>>::value,

"fmap requires a function type U(T)");

if (lst.isEmpty())

return List<U>();

else

return List<U>(f(lst.front()), fmap<U>(f, lst.pop_front()));

}

An astute reader will notice a similarity between fmap and the standard C++ algorithm transform in both semantics and interface. The power of the Standard Template Library can be traced back to its roots in functional programming.

The static_assert verifies that the the template argument F is convertible to a function type that takes T and returns U. This way fmap may be instantiated for a function pointer, function object (a class with an overloaded operator()), or a lambda, as long as its output type is convertible to U. Ultimately, these kind of constraints should be expressible as concepts.

The compiler is usually able to infer type arguments for a template function by analyzing the instantiation context. Unfortunately, inferring the return type of a functional argument like F in fmap is beyond its abilities, so you are forced to specify the type of U at the call site, as in this example (also, toupper is defined to return an int rather than char):

auto charLst2 = fmap<char>(toupper, charLst);

There is a common structure to recursive functions operating on functional data structures. They usually branch on, essentially, different constructors. In the implementation of fmap, we first check for an empty list — the result of the empty constructor — otherwise we deconstruct the (head, tail) constructor. We apply the function f to the head and then recurse into the tail.

Notice that fmap produces a new list of the same shape (number and arrangement of elements) as the original list. There are also algorithms that either change the shape of the list, or produce some kind of a “total” from a list. An example of the former is filter:

template<class T, class P>

List<T> filter(P p, List<T> lst)

{

static_assert(std::is_convertible<P, std::function<bool(T)>>::value,

"filter requires a function type bool(T)");

if (lst.isEmpty())

return List<T>();

if (p(lst.front()))

return List<T>(lst.front(), filter(p, lst.pop_front()));

else

return filter(p, lst.pop_front());

}

Totaling a list requires some kind of running accumulator and a function to process an element of a list and “accumulate” it in the accumulator, whatever that means. We also need to define an “empty” accumulator to start with. For instance, if we want to sum up the elements of a list of integers, we’d use an integer as an accumulator, set it initially to zero, and define a function that adds an element of a list to the accumulator.

In general such accumulation may produce different results when applied left to right or right to left (although not in the case of summation). Therefore we need two such algorithms, foldl (fold left) and foldr (fold right).

The right fold first recurses into the tail of the list to produce a partial accumulator then applies the function f to the head of the list and that accumulator:

template<class T, class U, class F>

U foldr(F f, U acc, List<T> lst)

{

static_assert(std::is_convertible<F, std::function<U(T, U)>>::value,

"foldr requires a function type U(T, U)");

if (lst.isEmpty())

return acc;

else

return f(lst.front(), foldr(f, acc, lst.pop_front()));

}

Conversely, the left fold first applies f to the head of the list and the accumulator that was passed in, and then calls itself recursively with the new accumulator and the tail of the list. Notice that, unlike foldr, foldl is tail recursive.

template<class T, class U, class F>

U foldl(F f, U acc, List<T> lst)

{

static_assert(std::is_convertible<F, std::function<U(U, T)>>::value,

"foldl requires a function type U(U, T)");

if (lst.isEmpty())

return acc;

else

return foldl(f, f(acc, lst.front()), lst.pop_front());

}

Again, the STL implements a folding algorithm as well, called accumulate. I’ll leave it to the reader to figure out which fold it implements, left or right, and why.

In C++ we can have procedures that instead of (or along with) producing a return value produce side effects. We can capture this pattern with forEach:

template<class T, class F>

void forEach(List<T> lst, F f)

{

static_assert(std::is_convertible<F, std::function<void(T)>>::value,

"forEach requires a function type void(T)");

if (!lst.isEmpty()) {

f(lst.front());

forEach(lst.pop_front(), f);

}

}

We can, for instance, use forEach to implement print:

template<class T>

void print(List<T> lst)

{

forEach(lst, [](T v)

{

std::cout << "(" << v << ") ";

});

std::cout << std::endl;

}

Singly-linked list concatenation is not a cheap operation. It takes O(N) time (there are however persistent data structures that can do this in O(1) time). Here’s the recursive implementation of it:

template

List concat(List const & a, List const & b)

{

if (a.isEmpty())

return b;

return List(a.front(), concat(a.pop_front(), b));

}

We can reverse a list using foldl in O(N) time. The trick is to use a new list as the accumulator:

template<class T>

List<T> reverse(List<T> const & lst)

{

return foldl([](List<T> const & acc, T v)

{

return List<T>(v, acc);

}, List<T>(), lst);

}

Again, all these algorithms can be easily implemented using iteration rather than recursion. In fact, once you define (input/output) iterators for a List, you can just use the STL algorithms.

Conclusion

A singly linked list is not the most efficient data structure in the world but it can easily be made persistent. What’s important is that a persistent list supports all the operation of a FIFO stack in constant time and is automatically thread safe. You can safely and efficiently pass such lists to and from threads without the need to synchronize (except for the internal synchronization built into shared pointers).

Complete code for this post is available on GitHub. It uses some advanced features of C++11. I compiled it with Visual Studio 2013.

Appendix: Haskell Implementation

Functional languages support persistent lists natively. But it’s not hard to implement lists explicitly. The following one liner is one such implementation in Haskell:

data List t = Empty | Cons t (List t)

This list is parameterized by the type parameter t (just like our C++ template was parameterized by T). It has two constructors, one called Empty and the other called Cons. The latter takes two arguments: a value of type t and a List of t — the tail. These constructors can be used for both the creation of new lists and for pattern-matching. For instance, here’s the implementation of cat (the function concat is already defined in the Haskell default library so I had to use a different name):

cat Empty lst = lst cat (Cons x tail) lst = Cons x (cat tail lst)

The selection between the empty and non-empty case is made through pattern matching on the first argument. The first line matches the pattern (constructor) Empty. The second line matches the Cons pattern and, at the same time, extracts the head and the tail of the list (extraction using pattern matching is thus much safer than calling head or tail because an empty list won’t match this pattern). It then constructs a new list with x as the head and the (recursive) concatenation of the first list’s tail with the second list. (I should mention that this recursive call is lazily evaluated in Haskell, so the cost of cat is amortized across many accesses to the list — more about lazy evaluation in the future.)