In category theory we never look inside objects. All information about objects is encoded in the arrows (morphisms) between them. In set theory, on the other hand, we express properties of sets through their elements. But there is a strong link between categories and sets, at least in the case of locally small categories. In those categories, morphisms between any two objects form a set. We call this set the hom-set.

Go one level up in abstraction and you have categories of functors, which are mappings between categories. In a functor category a functor is treated as an object, and a natural transformation — a mapping between functors– is treated as a morphism. So a hom-set in a functor category is a set of natural transformations between two functors. An interesting question arises: How is this set related to the hom-sets in the categories that are mapped by these functors? After all, they are sets in the same category of sets. The answer involves, as usual, a universal construction. This one is called an end.

Notation

The problem with category theory is that it deals with so many levels of abstraction that you quickly run out of fonts for your notation. I’ll try to stick to more or less the standard notation. I’ll use capital letters C, D, etc. for categories (script font would be nice, but it’s not very practical in a blog). The corresponding lower case letters, c, d — optionally with primes, like c', d' — will denote objects in those categories. I’ll use f, g, h, etc. for morphisms and F, G, H for functors. I’ll also use the terse notation for hom-sets, so the set of all morphisms between objects c and c' in category C will be simply C(c, c'). The set of natural transformations between two functors F and G, both mapping C to D, will be [C, D](F, G). I will not use parentheses for functors acting on objects or morphisms, so F acting on c will be simply F c (and similarly F f, when acting on f). But occasionally I’ll break the rules if it helps the presentation.

Natural Transformations

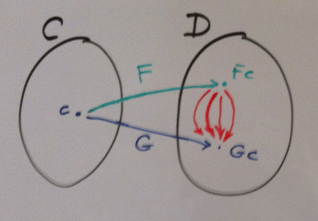

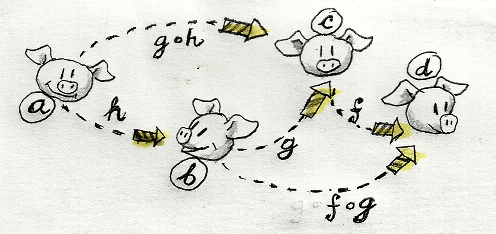

A natural transformation is a map between functors. So let’s start with two functors F and G, both going from category C to another category D. Let’s focus on one object in C, call it c. F maps c to F c and G maps c to G c. These two, F c and G c, are objects in D. As such they define a hom-set: the set of all morphisms from F c to G c denoted D(F c, G c). A natural transformation picks one morphism from every such hom-set. Not all picks are natural, as we’ll see soon.

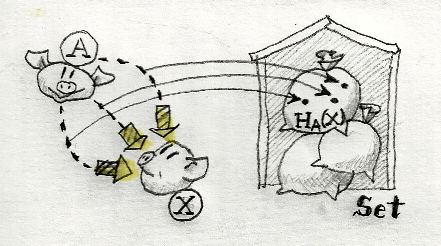

A hom-set, being a set, is also an object in Set — the category of sets. So let’s look at the hom-sets D(F c, G c) as objects in Set. There is one for every c. If we carefully pick one element from each, we will have a natural transformation (I said “carefully”). A natural transformation is a family of morphisms picked from hom-sets D(F c, G c), one for each c. If you think of those hom-sets as fibers growing from objects in C, a natural transformation is a cross-section through all these fibers.

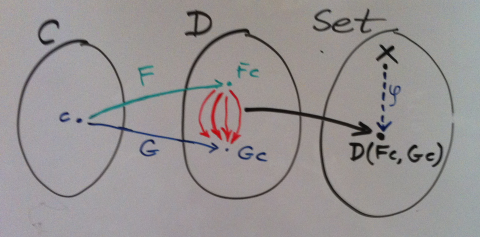

Here’s another way of looking at this. Let’s pick an arbitrary set in Set, call it X (sorry, I’m using a capital letter for an object in Set, but I do need lowercase x for its element). A function φ from X to the set D(F c, G c) maps an element x of X to a particular morphism in D(F c, G c). We can think of it as picking a component of some natural transformation. Each choice of x would potentially correspond to a different natural transformation. So the set X could be looked upon as representing some set of natural transformations. We still have to fill in a lot of blanks, but we are on the right track.

Since a natural transformation is a family of morphisms, we need a family of such functions from X to D(F c, G c), one for every c. Let’s call this family τ. When we fix c, it’s a function from X to D(F c, G c). When we fix x, it’s a precursor of a natural transformation: a family of morphisms picked from hom-sets.

The only thing missing from this picture is the naturality condition. Not all families of D(F c, G c) are natural. We need to account for the fact that our functors F and G not only map objects, but also morphisms.

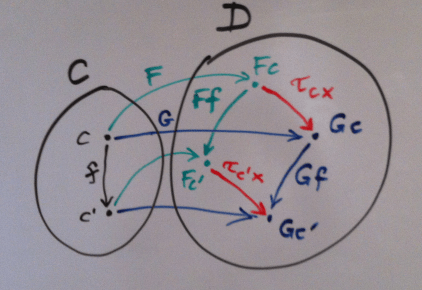

So let’s look at morphisms in C and how they are mapped to morphisms in D by, say, our functor F. We can pick two object in C, c and c'. Morphisms between those two form a hom-set C(c, c'). F maps this hom-set to another hom-set, D(F c, F c'). Similarly, G maps the same hom-set to D(G c, G c').

Four hom-sets defined by two functors F and G and two objects c and c’. A natural transformation is a recipe for picking red arrows.

Taken together, we have a diagram of four hom-sets between four objects: F c, F c', G c, and G c'. Fixing a morphism f from c to c' (an element of C(c, c')) picks two morphisms, one F f from D(F c, F c') and one G f from D(G c, G c'), given the functoriality of F and G. Fixing an x in X picks two morphisms, one τc x from D(F c, G c) and one τc' x from D(F c', G c'). These four better commute:

G f . τc x = τc' x . F f

That’s the naturality condition. Any τ that satisfies this condition defines a set of natural transformations, one for each x.

Wedges

All this time I’ve been setting up the scene for one important insight. The set X and the family of functions τ look a lot like a cone (see my blog post about limits). Except that, instead on one functor, we have two, and τ is not really a natural transformation. But we are getting close. And if we can carve out something cone-like out of this construction, than we could maybe find something limit-like. And indeed the cone-like object is called a wedge and the limit-like thing is called an end, and in our case the end would be a set of all natural transformations from F to G. So let’s work this thing out.

If we were constructing a cone, we’d start with a functor from our source category C to the target category — Set in this case. That’s easy to define for objects: c goes into the set D(F c, G c). But we run into a problem with morphisms. Suppose we want to map a morphism h that goes from c to c':

h : c -> c'

Its image should be a function from D(F c, G c) to D(F c', G c'). It’s a function that maps morphisms to morphisms. Let’s see what morphisms are at our disposal. We have:

F h : F c -> F c' G h : G c -> G c'

How can we turn a morphism f from D(F c, G c)

f : F c -> G c

into a morphism f' from D(F c', G c'):

f' : F c' -> G c'

One thing we could do is to post-compose G h after f to get to G c'; but there is no way to get anywhere from F c'. So it can’t be that simple.

But notice one thing. Even though τ maps elements of X to “diagonal” hom-sets (by diagonal I mean that the argument c is repeated in D(F c, G c)), naturality condition involves off-diagonal hom-sets, like D(F c, F c') and D(G c, G c') (c potentially different from c'). So maybe we should open our minds to those off-diagonal hom-sets in our search of a functor? How about a functor that maps a pair of elements (c, c') to a hom-set D(F c, G c')? Let’s see if we can figure out its action on morphisms.

Now, since we are constructing a functor of two arguments, we have to define its action on a pair of morphisms, (f, g).

f : c -> c' g : d -> d'

The image of this pair should be a function in Set that maps D(F c, G d) into D(F c', G d'). Unfortunately, we run into the same problem again. Given h : F c -> G d, we can follow it with G g : G d -> G d', but there is no way we can move anywhere from F c'. The only morphism at our disposal goes the wrong way, F f : F c -> F c'. If we could only reverse it!

Ah! but functors that go “the wrong way” on morphisms are well known. They are called contravariant functors, as opposed to the good old covariant functors that we have grown to love and cherish. What we need is a functor that’s contravariant in the first argument and covariant in the second. Such functors even have a name: they are called profunctors.

So, given a pair of morphisms (f, g) our profunctor Snat will map a morphism from D(F c', G d) to a morphism from D(F c, G d'). Notice that this time I have inverted c and c'.

Given h : F c' -> G d, we can easily construct a correpsponding morphism in D(F c, G d') by this composition:

G g . h . F f : F c' -> G d

So that’s our action of Snat on a pair of morphisms from C. It turns a morphism h into:

(Snat f g) h = G g . h . F f

Let’s summarize what we have so far: We have a profunctor Snat, a set X, and a family of morphisms τ from X to diagonal elements Snat c c. We are not interested in defining τ for off-diagonal elements of Snat. What remains is to impose some kind of generic condition on τ that would let it generate natural transformations only. We would like to formulate this condition in terms of a general profunctor S, if possible.

What’s the minimal consistency condition on τ, given that it only generates diagonal elements S c c? We need a way to somehow connect two such objects, say S c c and S c' c'. Suppose we have a morphism f : c -> c'. How can we use this morphism to operate on S c c and S c' c'? A profunctor S can be used to map a pair of morphisms, so how about pairing our f with something obvious that always exists, like the identity morphism id? Let’s try it:

S idc f : S c c -> S c c' S f idc' : S c' c' -> S c c'

(Notice the inversion of c and c' when f is used as the first argument — that’s our contravariance in action.) We have found two ways to get from two diagonal elements to the same non-diagonal element of S. Together with τc and τc' they form a diamond. This diamond better commute or we’re in trouble.

S idc f . τc = S f idc' . τc'

Now we can finally define a wedge for an arbitrary profunctor S. A wedge for S consists of an object X and a family of morphisms τc from X to S c c that satisfy the wedge condition above.

And if we plug in our special profunctor Snat that maps pairs of objects to hom-sets, the wedge condition turns into the naturality condition for our two functors. Let’s check this out.

Remember, this is how Snat acts on a pair of morphisms f and g:

(Snat f g) h = G g . h . F f

Substituting identities in the right places, we get (remember, functors turn identities into identities):

(Snat idc f) h = G f . h (Snat f idc') h' = h' . F f

Notice that h and h' are morphisms in D but, at the same time, elements of sets S c c and S c' c' in the wedge condition. They are given, respectively, by the action of τc and τc’ on an element x of X. The wedge condition for Snat will therefore post-compose τc and pre-compose τc:

G f . τc = τc' . F f

And this is exactly the naturality condition for components of τ. It means that τ that satisfies the wedge condition is a natural transformation for any choice of x.

Dinatural transformations

This definition of a wedge looks almost like the definition of a cone, except that the commuting conditions in a cone were expressed in terms of naturality of the transformation between the diagonal functor ΔX and the functor F. Here, we could also say that the object X is an image of a diagonal profunctor ΔX — trivially defined to map pairs of objects from C to an object X, and pairs of morphisms to the identity morphism on X.

A wedge (Strictly speaking, a profunctor is a mapping from CopxC to D — the “op” accounting for the reversal of the direction of morphisms in the first argument)

So what we need to complete the picture is some generalized notion of a natural transformation between two profunctors R and S. Since we are only interested in the mapping of diagonal elements of profunctors, this transformation will be called a dinatural transformation (diagonally natural). All we need is to expand the top vertex of the diamond diagram (the wedge condition) to create the commuting hexagon below.

S idc f . τc . R f idc = S f idc' . τc' . R idc' f

With this dinaturality condition we can define a wedge for any profunctor S with a vertex X as a dinatural transformation between ΔX and S.

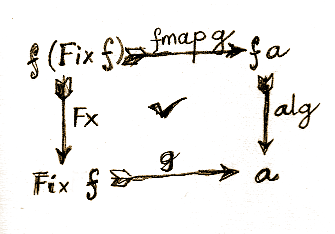

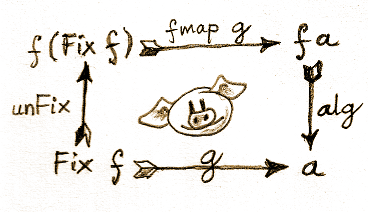

Now, just as we have defined a limit as a universal cone, we can define an end as a universal wedge. An end is an object End S and a dinatural transformation ω such that for any other wedge (X, τ) there is a unique morphism h from X to End S for which all the triangles in the following diagram commute:

In particular, since the wedges for our profunctor Snat defined natural transformations, their end defines the set of all natural transformations between the functors F and G: [C, D](F, G).

There is special notation for an end using the integral symbol. We are “integrating” a profunctor S along a diagnonal over all objects c in category C.

End S = ∫ c S(c, c)

Using this notation, the set of natural transformations can be written as the following end:

[C, D](F, G) = ∫ c D(F c, G c)

Note: This is a bit of abuse of notation that happens quite often in category theory. The integral sign makes more sense for coends, which are duals of ends. Coends are related to colimits, which include coproducts, which are the category theory proxies for sums. In this sense, a coend is a generalization of a sum; just as an integral is an infinite continuous sum. By the same token, an end is a generalization of a product. Unfortunately, there is no common symbol for a continuous product in calculus, so we are stuck with the integral symbol.

In Haskell, ends become universal quantifiers, hence this definition of natural transformation from Edward Kmett’s category extras (here f and g are functors):

type f :~> g = forall a. f a -> g a type Natural f g = f :~> g

You can find more about representing profunctors, dinatural transformations, and ends in Haskell in Edward’s blog.

The Moment of Zen

You can think of a hom-set as defining a mapping: It takes a pair of objects and generates a set of morphisms — an object in Set. A profunctor generalizes this idea. It takes a pair of objects and generates a hom-set-like object in a category that’s not necessarily the category of sets. The mapping from a pair of objects to a hom-set is functorial: its action on pairs of morphisms is well defined as well. Except that this action is contravariant in the first argument and covariant in the second. And so is a profunctor which imitates it.

We’ve seen before how a functor can embed a simple graph into a category and define a limit. The limit embodies the structure of this graph in a single object. A profunctor embeds a structure of a hom-set into a category. An end then embodies this structure in a single object. When this hom-set structure is fashioned using two functors, the end becomes a set of mappings between those two functors — a set of natural transformations. But nothing stops us from fashioning more complex hom-set-like structures and finding their ends.

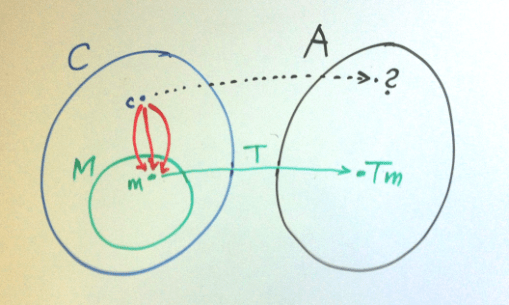

One such construction I’ve had my eyes on for a long itme is called the Kan extension. To give you an idea, imagine a functor T that’s defined on a sub-category M of a bigger category C. It maps it into a category A. The question is, can we extend, or interpolate, this functor over the rest of C? How would we define its value on an object c that’s not in M? The trick is to look at all the hom-sets that go from c to objects in M.

Our extended functor will have to map not only c to an object in A, but also all those hom-sets to hom-sets in A. After all, that’s what functors do. This mapping of hom-sets looks very much like a profunctor. It has to be contravariant in its source and covariant in its target. If this profunctor has an end, that’s a perfect candidate for the image of c under the extended functor. That, in a nutshell, is the idea behind the right Kan extension (the left one is, predictably, built with coends). But that’s a topic for another blog post.