This is part 26 of Categories for Programmers. Previously: Algebras for Monads. See the Table of Contents.

There are many intuitions that we may attach to morphisms in a category, but we can all agree that if there is a morphism from the object a to the object b than the two objects are in some way “related.” A morphism is, in a sense, the proof of this relation. This is clearly visible in any poset category, where a morphism is a relation. In general, there may be many “proofs” of the same relation between two objects. These proofs form a set that we call the hom-set. When we vary the objects, we get a mapping from pairs of objects to sets of “proofs.” This mapping is functorial — contravariant in the first argument and covariant in the second. We can look at it as establishing a global relationship between objects in the category. This relationship is described by the hom-functor:

C(-, =) :: Cop × C -> Set

In general, any functor like this may be interpreted as establishing a relation between objects in a category. A relation may also involve two different categories C and D. A functor, which describes such a relation, has the following signature and is called a profunctor:

p :: Dop × C -> Set

Mathematicians say that it’s a profunctor from C to D (notice the inversion), and use a slashed arrow as a symbol for it:

C ↛ D

You may think of a profunctor as a proof-relevant relation between objects of C and objects of D, where the elements of the set symbolize proofs of the relation. Whenever p a b is empty, there is no relation between a and b. Keep in mind that relations don’t have to be symmetric.

Another useful intuition is the generalization of the idea that an endofunctor is a container. A profunctor value of the type p a b could then be considered a container of bs that are keyed by elements of type a. In particular, an element of the hom-profunctor is a function from a to b.

In Haskell, a profunctor is defined as a two-argument type constructor p equipped with the method called dimap, which lifts a pair of functions, the first going in the “wrong” direction:

class Profunctor p where

dimap :: (c -> a) -> (b -> d) -> p a b -> p c d

The functoriality of the profunctor tells us that if we have a proof that a is related to b, then we get the proof that c is related to d, as long as there is a morphism from c to a and another from b to d. Or, we can think of the first function as translating new keys to the old keys, and the second function as modifying the contents of the container.

For profunctors acting within one category, we can extract quite a lot of information from diagonal elements of the type p a a. We can prove that b is related to c as long as we have a pair of morphisms b->a and a->c. Even better, we can use a single morphism to reach off-diagonal values. For instance, if we have a morphism f::a->b, we can lift the pair <f, idb> to go from p b b to p a b:

dimap f id pbb :: p a b

Or we can lift the pair <ida, f> to go from p a a to p a b:

dimap id f paa :: p a b

Dinatural Transformations

Since profunctors are functors, we can define natural transformations between them in the standard way. In many cases, though, it’s enough to define the mapping between diagonal elements of two profunctors. Such a transformation is called a dinatural transformation, provided it satisfies the commuting conditions that reflect the two ways we can connect diagonal elements to non-diagonal ones. A dinatural transformation between two profunctors p and q, which are members of the functor category [Cop × C, Set], is a family of morphisms:

αa :: p a a -> q a a

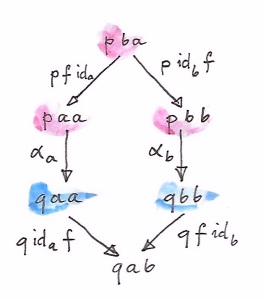

for which the following diagram commutes, for any f::a->b:

Notice that this is strictly weaker than the naturality condition. If α were a natural transformation in [Cop × C, Set], the above diagram could be constructed from two naturality squares and one functoriality condition (profunctor q preserving composition):

Notice that a component of a natural transformation α in [Cop × C, Set] is indexed by a pair of objects α a b. A dinatural transformation, on the other hand, is indexed by one object, since it only maps diagonal elements of the respective profunctors.

Ends

We are now ready to advance from “algebra” to what could be considered the “calculus” of category theory. The calculus of ends (and coends) borrows ideas and even some notation from traditional calculus. In particular, the coend may be understood as an infinite sum or an integral, whereas the end is similar to an infinite product. There is even something that resembles the Dirac delta function.

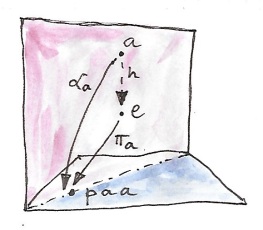

An end is a generalization of a limit, with the functor replaced by a profunctor. Instead of a cone, we have a wedge. The base of a wedge is formed by diagonal elements of a profunctor p. The apex of the wedge is an object (here, a set, since we are considering Set-valued profunctors), and the sides are a family of functions mapping the apex to the sets in the base. You may think of this family as one polymorphic function — a function that’s polymorphic in its return type:

α :: forall a . apex -> p a a

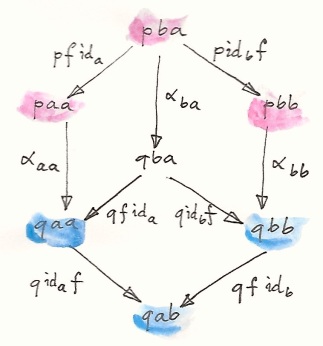

Unlike in cones, within a wedge we don’t have any functions that would connect the vertices that form the base. However, as we’ve seen earlier, given any morphism f::a->b in C, we can connect both p a a and p b b to the common set p a b. We therefore insist that the following diagram commute:

This is called the wedge condition. It can be written as:

p ida f ∘ αa = p f idb ∘ αb

Or, using Haskell notation:

dimap id f . alpha = dimap f id . alpha

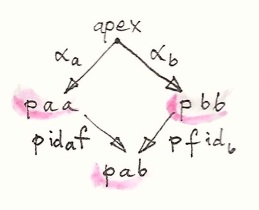

We can now proceed with the universal construction and define the end of p as the universal wedge — a set e together with a family of functions π such that for any other wedge with the apex a and a family α there is a unique function h::a->e that makes all triangles commute:

πa ∘ h = αa

The symbol for the end is the integral sign, with the “integration variable” in the subscript position:

∫c p c c

Components of π are called projection maps for the end:

πa :: ∫c p c c -> p a a

Note that if C is a discrete category (no morphisms other than the identities) the end is just a global product of all diagonal entries of p across the whole category C. Later I’ll show you that, in the more general case, there is a relationship between the end and this product through an equalizer.

In Haskell, the end formula translates directly to the universal quantifier:

forall a. p a a

Strictly speaking, this is just a product of all diagonal elements of p, but the wedge condition is satisfied automatically due to parametricity (I’ll explain it in a separate blog post). For any function f :: a -> b, the wedge condition reads:

dimap f id . pi = dimap id f . pi

or, with type annotations:

dimap f idb . pib = dimap ida f . pia

where both sides of the equation have the type:

Profunctor p => (forall c. p c c) -> p a b

and pi is the polymorphic projection:

pi :: Profunctor p => forall c. (forall a. p a a) -> p c c pi e = e

Here, type inference automatically picks the right component of e.

Just as we were able to express the whole set of commutation conditions for a cone as one natural transformation, likewise we can group all the wedge conditions into one dinatural transformation. For that we need the generalization of the constant functor Δc to a constant profunctor that maps all pairs of objects to a single object c, and all pairs of morphisms to the identity morphism for this object. A wedge is a dinatural transformation from that functor to the profunctor p. Indeed, the dinaturality hexagon shrinks down to the wedge diamond when we realize that Δc lifts all morphisms to one identity function.

Ends can also be defined for target categories other than Set, but here we’ll only consider Set-valued profunctors and their ends.

Ends as Equalizers

The commutation condition in the definition of the end can be written using an equalizer. First, let’s define two functions (I’m using Haskell notation, because mathematical notation seems to be less user-friendly in this case). These functions correspond to the two converging branches of the wedge condition:

lambda :: Profunctor p => p a a -> (a -> b) -> p a b lambda paa f = dimap id f paa rho :: Profunctor p => p b b -> (a -> b) -> p a b rho pbb f = dimap f id pbb

Both functions map diagonal elements of the profunctor p to polymorphic functions of the type:

type ProdP p = forall a b. (a -> b) -> p a b

Functions lambda and rho have different types. However, we can unify their types, if we form one big product type, gathering together all diagonal elements of p:

newtype DiaProd p = DiaProd (forall a. p a a)

The functions lambda and rho induce two mappings from this product type:

lambdaP :: Profunctor p => DiaProd p -> ProdP p lambdaP (DiaProd paa) = lambda paa rhoP :: Profunctor p => DiaProd p -> ProdP p rhoP (DiaProd paa) = rho paa

The end of p is the equalizer of these two functions. Remember that the equalizer picks the largest subset on which two functions are equal. In this case it picks the subset of the product of all diagonal elements for which the wedge diagrams commute.

Natural Transformations as Ends

The most important example of an end is the set of natural transformations. A natural transformation between two functors F and G is a family of morphisms picked from hom-sets of the form C(F a, G a). If it weren’t for the naturality condition, the set of natural transformations would be just the product of all these hom-sets. In fact, in Haskell, it is:

forall a. f a -> g a

The reason it works in Haskell is because naturality follows from parametricity. Outside of Haskell, though, not all diagonal sections across such hom-sets will yield natural transformations. But notice that the mapping:

<a, b> -> C(F a, G b)

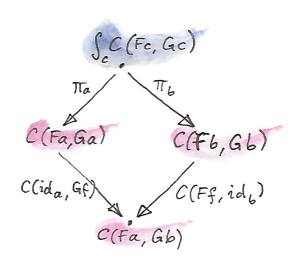

is a profunctor, so it makes sense to study its end. This is the wedge condition:

Let’s just pick one element from the set ∫c C(F c, G c). The two projections will map this element to two components of a particular transformation, let’s call them:

τa :: F a -> G a τb :: F b -> G b

In the left branch, we lift a pair of morphisms <ida, G f> using the hom-functor. You may recall that such lifting is implemented as simultaneous pre- and post-composition. When acting on τa the lifted pair gives us:

G f ∘ τa ∘ ida

The other branch of the diagram gives us:

idb ∘ τb ∘ F f

Their equality, demanded by the wedge condition, is nothing but the naturality condition for τ.

Coends

As expected, the dual to an end is called a coend. It is constructed from a dual to a wedge called a cowedge (pronounced co-wedge, not cow-edge).

The symbol for a coend is the integral sign with the “integration variable” in the superscript position:

∫ c p c c

Just like the end is related to a product, the coend is related to a coproduct, or a sum (in this respect, it resembles an integral, which is a limit of a sum). Rather than having projections, we have injections going from the diagonal elements of the profunctor down to the coend. If it weren’t for the cowedge conditions, we could say that the coend of the profunctor p is either p a a, or p b b, or p c c, and so on. Or we could say that there exists such an a for which the coend is just the set p a a. The universal quantifier that we used in the definition of the end turns into an existential quantifier for the coend.

This is why, in pseudo-Haskell, we would define the coend as:

exists a. p a a

The standard way of encoding existential quantifiers in Haskell is to use universally quantified data constructors. We can thus define:

data Coend p = forall a. Coend (p a a)

The logic behind this is that it should be possible to construct a coend using a value of any of the family of types p a a, no matter what a we chose.

Just like an end can be defined using an equalizer, a coend can be described using a coequalizer. All the cowedge conditions can be summarized by taking one gigantic coproduct of p a b for all possible functions b->a. In Haskell, that would be expressed as an existential type:

data SumP p = forall a b. SumP (b -> a) (p a b)

There are two ways of evaluating this sum type, by lifting the function using dimap and applying it to the profunctor p:

lambda, rho :: Profunctor p => SumP p -> DiagSum p lambda (SumP f pab) = DiagSum (dimap f id pab) rho (SumP f pab) = DiagSum (dimap id f pab)

where DiagSum is the sum of diagonal elements of p:

data DiagSum p = forall a. DiagSum (p a a)

The coequalizer of these two functions is the coend. A coequilizer is obtained from DiagSum p by identifying values that are obtained by applying lambda or rho to the same argument. Here, the argument is a pair consisting of a function b->a and an element of p a b. The application of lambda and rho produces two potentially different values of the type DiagSum p. In the coend, these two values are identified, making the cowedge condition automatically satisfied.

The process of identification of related elements in a set is formally known as taking a quotient. To define a quotient we need an equivalence relation ~, a relation that is reflexive, symmetric, and transitive:

a ~ a if a ~ b then b ~ a if a ~ b and b ~ c then a ~ c

Such a relation splits the set into equivalence classes. Each class consists of elements that are related to each other. We form a quotient set by picking one representative from each class. A classic example is the definition of rational numbers as pairs of whole numbers with the following equivalence relation:

(a, b) ~ (c, d) iff a * d = b * c

It’s easy to check that this is an equivalence relation. A pair (a, b) is interpreted as a fraction a/b, and fractions whose numerator and denominator have a common divisor are identified. A rational number is an equivalence class of such fractions.

You might recall from our earlier discussion of limits and colimits that the hom-functor is continuous, that is, it preserves limits. Dually, the contravariant hom-functor turns colimits into limits. These properties can be generalized to ends and coends, which are a generalization of limits and colimits, respectively. In particular, we get a very useful identity for converting coends to ends:

Set(∫ x p x x, c) ≅ ∫x Set(p x x, c)

Let’s have a look at it in pseudo-Haskell:

(exists x. p x x) -> c ≅ forall x. p x x -> c

It tells us that a function that takes an existential type is equivalent to a polymorphic function. This makes perfect sense, because such a function must be prepared to handle any one of the types that may be encoded in the existential type. It’s the same principle that tells us that a function that accepts a sum type must be implemented as a case statement, with a tuple of handlers, one for every type present in the sum. Here, the sum type is replaced by a coend, and a family of handlers becomes an end, or a polymorphic function.

Ninja Yoneda Lemma

The set of natural transformations that appears in the Yoneda lemma may be encoded using an end, resulting in the following formulation:

∫z Set(C(a, z), F z) ≅ F a

There is also a dual formula:

∫ z C(z, a) × F z ≅ F a

This identity is strongly reminiscent of the formula for the Dirac delta function (a function δ(a - z), or rather a distribution, that has an infinite peak at a = z). Here, the hom-functor plays the role of the delta function.

Together these two identities are sometimes called the Ninja Yoneda lemma.

To prove the second formula, we will use the consequence of the Yoneda embedding, which states that two objects are isomorphic if and only if their hom-functors are isomorphic. In other words a ≅ b if and only if there is a natural transformation of the type:

[C, Set](C(a, -), C(b, =))

that is an isomorphism.

We start by inserting the left-hand side of the identity we want to prove inside a hom-functor that’s going to some arbitrary object c:

Set(∫ z C(z, a) × F z, c)

Using the continuity argument, we can replace the coend with the end:

∫z Set(C(z, a) × F z, c)

We can now take advantage of the adjunction between the product and the exponential:

∫z Set(C(z, a), c(F z))

We can “perform the integration” by using the Yoneda lemma to get:

c(F a)

(Notice that we used the contravariant version of the Yoneda lemma, since c(F z) is contravariant in z.)

This exponential object is isomorphic to the hom-set:

Set(F a, c)

Finally, we take advantage of the Yoneda embedding to arrive at the isomorphism:

∫ z C(z, a) × F z ≅ F a

Profunctor Composition

Let’s explore further the idea that a profunctor describes a relation — more precisely, a proof-relevant relation, meaning that the set p a b represents the set of proofs that a is related to b. If we have two relations p and q we can try to compose them. We’ll say that a is related to b through the composition of q after p if there exist an intermediary object c such that both q b c and p c a are non-empty. The proofs of this new relation are all pairs of proofs of individual relations. Therefore, with the understanding that the existential quantifier corresponds to a coend, and the cartesian product of two sets corresponds to “pairs of proofs,” we can define composition of profunctors using the following formula:

(q ∘ p) a b = ∫ c p c a × q b c

Here’s the equivalent Haskell definition from Data.Profunctor.Composition, after some renaming:

data Procompose q p a b where Procompose :: q a c -> p c b -> Procompose q p a b

This is using generalized algebraic data type, or GADT syntax, in which a free type variable (here c) is automatically existentially quanitified. The (uncurried) data constructor Procompose is thus equivalent to:

exists c. (q a c, p c b)

The unit of so defined composition is the hom-functor — this immediately follows from the Ninja Yoneda lemma. It makes sense, therefore, to ask the question if there is a category in which profunctors serve as morphisms. The answer is positive, with the caveat that both associativity and identity laws for profunctor composition hold only up to natural isomorphism. Such a category, where laws are valid up to isomorphism, is called a bicategory (which is more general than a 2-category). So we have a bicategory Prof, in which objects are categories, morphisms are profunctors, and morphisms between morphisms (a.k.a., two-cells) are natural transformations. In fact, one can go even further, because beside profunctors, we also have regular functors as morphisms between categories. A category which has two types of morphisms is called a double category.

Profunctors play an important role in the Haskell lens library and in the arrow library.

Challenge

- Write explicitly the cowedge condition for a coend.

Next: Kan extensions.

March 31, 2017 at 4:44 am

Why do mathematicians invert the arrow from C to D when, intuitively, the relation goes from D to C?

April 3, 2017 at 9:33 am

“In Haskell, the end formula translates directly to the universal quantifier:

forall a. p a a”

It’s not really clear what formula is implied here and why it translates to… this? What is this even? A data type? I am utterly confused.

April 3, 2017 at 12:26 pm

Yes, it’s a data type. Think of it as an infinite tuple (product) that contains values for all possible types. Of course, the only examples we can provide are polymorphic functions — you get one function for every possible type. Here’s a complete example:

April 4, 2017 at 11:38 pm

So then End (NatPro [] Maybe) is a collection of images of π morphisms? And for each one of those, we have a π: apex -> p a a, but what type would be the apex then? And how would the π morphism itself look?

April 5, 2017 at 10:21 am

The end is a product of individual functions collectively given by one formula

safeHead. You can always pick a particular component; for instance, forIntyou get:Notice that

safeHeadIntis no longer a polymorphic function. You can’t call it with a list ofChar.In fact, if you define:

you can use the definition of

pifrom the post to project the end:June 9, 2018 at 1:00 pm

I’m confused by the dual formula in the ninja Yoneda lemma. In particular, in

∫^z C(a, z) × F z, it doesn’t seem to me like C(a, -) × F is a profunctor. Is F a covariant functor in ∫_z Set(C(a, z), F z) ≅ F a and a contravariant functor in ∫^z C(a, z) × F z ≅ F a?

June 9, 2018 at 2:35 pm

You’re right. There are two versions of the Ninja Yoneda lemma, one for covariant and one for contravariant functors. The one I used is for contravariant functors, and indeed cF z is contravariant in z (as long as F is covariant). I’ll add explanation to this post. Thanks for catching it.

September 11, 2018 at 7:14 am

In youtube video series “end and coends” is the last thing you explain. Do you maybe recommend to skip this chapter till the end of the book?

September 11, 2018 at 10:05 am

No, I wouldn’t recommend skipping it. In the book, I use coends in making connection between Lawvere theories and monads.

September 13, 2018 at 4:00 am

In the definition of end as universal wedge you call other wedge’s apex as “a”. Is it same “a” as in p a a (target of πa and αa in the picture)? Or i can rename it to e’ and not change p a a?

September 13, 2018 at 4:59 pm

Oops, this is just an accident. It shouldn’t be the same a.

September 17, 2018 at 7:28 am

Few trivial comments for clarity.

“These functions have different types.” – last functions mentioned in text are of type ProdP but it’s not about them.

I’d write “Functions lambda and rho have different types.”

“Their equality, demanded by the wedge condition” – in the sense they both end up in same element of C(Fa, Gb); so being applied on some Fa both give same Gb (naturality square comutes).

September 18, 2018 at 7:41 am

“fractions that have a common divisor are identified” – what means “identified”? 1/3 and 2/3 have common divisor but are not equivalent; representatives may have same divisor; or maybe it should be “fractions that have a common ratio” (as 1/2 and 2/4)?

December 7, 2018 at 4:26 am

You should cite the source of the stuff you use, for example the “Ninja Yoneda lemma” actually comes from this paper https://arxiv.org/pdf/1501.02503.pdf [Prop. 2.1]

May 16, 2019 at 2:48 am

I don’t quite understand why

<a, b> -> C(F a, G b)

is a profunctor, it seems like a:

CxC->Set

to me

May 16, 2019 at 4:16 am

Consider what it does to morphisms. That’s where the difference is.

September 4, 2019 at 2:30 am

I’m stuck with the “inversion” in the direction of the profunctor.

If the intuition is that a profunctor represents the ways in which two objects are related (which is what the hom-functor tells), if we generalize the idea to two different categories, and we define p :: D^op x C -> Set, as the contravariant element is D, which corresponds to the domain part in the hom-functor, and the covariant element is C, which corresponds to the codomain part in the hom-functor, are we not relating elements in D with elements in C, so the profuntor goes from D to C?

September 5, 2019 at 12:01 am

Is there any reason why the arrow which represents a profuctor is inverted? I mean that, if we take the hom-profuctor p :: C^op x C -> Set, as each element p a b represents the set of “proofs” from a to b then, if we generalise it to C^op x D -> Set, we are relating things from C to D so, intuitively, the profuctor goes C -/-> D. For instance, Fong&Spivak’s Seven Sketches of Composionality presents profuctors without inverting the arrow but I’ve found many resources in which it is inverted. Is there any reason to do so?

September 10, 2019 at 5:26 pm

It’s a convention, but there are reasons for it. They come up when you consider a bicategory of profunctors, where profunctors serve as morphisms.

September 25, 2019 at 10:24 am

In Haskell definition,

forallis used for bothEndandCoend. Howeverforallis not the same in different contexts.I tried

Endas followsbash-3.2$ ghci GHCi, version 8.6.5: http://www.haskell.org/ghc/ 😕 for help Prelude> type End p = forall x. p x x <interactive>:1:22: error: Illegal symbol '.' in type Perhaps you intended to use RankNTypes or a similar language extension to enable explicit-forall syntax: forall <tvs>. <type> Prelude> :set -XExistentialQuantification Prelude> type End p = forall x. p x x <interactive>:3:1: error: • Illegal polymorphic type: forall x. p x x Perhaps you intended to use RankNTypes or Rank2Types • In the type synonym declaration for ‘End’ Prelude> :set -XScopedTypeVariables Prelude> type End p = forall x. p x x <interactive>:5:1: error: • Illegal polymorphic type: forall x. p x x Perhaps you intended to use RankNTypes or Rank2Types • In the type synonym declaration for ‘End’ Prelude> :set -XRankNTypes Prelude> type End p = forall x. p x x Prelude> :i End type End (p :: * -> * -> *) = forall x. p x x -- Defined at <interactive>:7:1By contrast, I got

Coend, likebash-3.2$ ghci GHCi, version 8.6.5: http://www.haskell.org/ghc/ 😕 for help Prelude> data Coend p = forall a. Coend (p a a) <interactive>:1:16: error: Not a data constructor: ‘forall’ Perhaps you intended to use ExistentialQuantification Prelude> :set -XScopedTypeVariables Prelude> data Coend p = forall a. Coend (p a a) <interactive>:3:16: error: • Data constructor ‘Coend’ has existential type variables, a context, or a specialised result type Coend :: forall (p :: * -> * -> *) a. p a a -> Coend p (Enable ExistentialQuantification or GADTs to allow this) • In the definition of data constructor ‘Coend’ In the data type declaration for ‘Coend’ Prelude> :set -XRankNTypes Prelude> data Coend p = forall a. Coend (p a a) <interactive>:5:16: error: • Data constructor ‘Coend’ has existential type variables, a context, or a specialised result type Coend :: forall (p :: * -> * -> *) a. p a a -> Coend p (Enable ExistentialQuantification or GADTs to allow this) • In the definition of data constructor ‘Coend’ In the data type declaration for ‘Coend’ Prelude> :set -XExistentialQuantification Prelude> data Coend p = forall a. Coend (p a a) Prelude> :i Coend data Coend (p :: * -> * -> *) = forall a. Coend (p a a) -- Defined at <interactive>:7:1 Prelude> :t Coend Coend :: p a a -> Coend pHaskell needs

RankNTypesversion offorallforEndbutExistentialQuantificationversion offorallforCoend.So Haskell actually has got direct and precise sense of

ExistsforCoend. Is it right?October 9, 2019 at 6:21 am

“We can now proceed with the universal construction and define the end of p as the uinversal wedge” <- small spelling mistake.

March 14, 2020 at 11:15 am

I found that there are some names confusing about Yoneda Lemma. So I list them here. If I am wrong, correct me. Very thanks!

In chapter 15, you mentioned Yoneda Lemma and Co-Yoneda Lemma:

Yoneda lemma:

Nat(C(a, -), F) ≅ Fa when F is covariant

Co-Yoneda lemma:

Nat(C(-, a), F) ≅ Fa when F is contravariant

In this chapter, you mentioned Ninja Yoneda Lemma and Co-Ninja Yoneda Lemma (duel version of Ninja Yoneda Lemma):

Ninja Yoneda Lemma 1:

∫_z Set(C(a,z), Fz) ≅ Fa when F is covariant (corresponds to Yoneda lemma)

Ninja Yoneda Lemma 2:

∫_z Set(C(z,a), Fz) ≅ Fa when F is contravariant (corresponds to Co-Yoneda lemma)

Ninja Co-yoneda Lemma 1:

∫^z (C(z,a) x Fz) ≅ Fa when F is covariant (duel version of Ninja Yoneda Lemma 1)

Ninja Co-yoneda Lemma 2:

∫^z (C(a,z) x Fz) ≅ Fa when F is contravariant (duel version of Ninja Yoneda Lemma 2)

March 14, 2020 at 11:59 am

You’re right, the nomenclature is not clear. I should probably rename Co-Yoneda in chapter 15 to contravariant Yoneda and reserve Co-Yoneda for the Ninja version using an end.

March 15, 2020 at 3:09 am

The “q b c” also wrong. It should be p c b.

March 15, 2020 at 8:21 am

Except that “p c a should be p c a” and “q b c should be q c b”

There also some typos in

“data Procompose q p a b where

Procompose :: q a c -> p c b -> Procompose q p a b”

and

“exists c. (q a c, p c b)”

They should be

“data Procompose q p a b where

Procompose :: q c b -> p a c -> Procompose q p a b”

and

“exists c. (q c b, p a c)”

See http://hackage.haskell.org/package/profunctors-5.5.2/docs/Data-Profunctor-Composition.html#t:Procompose

Procompose :: p x c -> q d x -> Procompose p q d cThey compose p∘q, you compose q∘p, so it cause some confusion.