I’m not fond of arguments based on lack of imagination. “There’s no way this code may fail!” might be a sign of great confidence or the result of ignorance. The inability to come up with a counterexample doesn’t prove a theorem. And yet there is one area of programming where such arguments work, and are quite useful. These are parametricity arguments: free theorems about polymorphic functions. Fortunately, there is solid theory behind parametricity. Free theorems are not based on ignorance. So I decided to read the relevant papers (see bibliography at the end of this post) and write a blog about it. How hard could it be? A few months and several failed attempts later I realized how naive I was. But I think I finally understand the basics enough to explain them in relatively simple terms.

Motivation

Here’s a classic example — a function that takes a list of arbitrary type a and returns a list of the same type:

r :: [a] -> [a]

What can this function do? Since it has to work with any type of list element, it can’t do anything type-specific. It can’t modify the elements or invent new ones. So all it can do is rearrange them, duplicate, or remove. Can you think of anything else?

The questions it a little tricky because it all depends on the kind of polymorphism your language supports. In Haskell, where we have parametric polymorphism, the above statement is for the most part true (modulo termination worries). In C++, which supports ad-hoc polymorphism, a generic function like:

template<class T> list<T> r(list<T>);

can do all kinds of weird things.

Parametric polymorphism means that a function will act on all types uniformly, so the above declaration of r indeed drastically narrows down the possibilities.

For instance, consider what happens when you map any function of the type:

f :: a -> b

over a list of a. You can either apply map before or after acting on it with r. It shouldn’t matter whether you first modify the elements of the list and then rearrange them, or first rearrange and then modify them. The result should be the same:

r (map f as) = map f (r as)

But is it true just because we can’t imagine how it may fail, or can we make a formal argument to prove it?

Let’s Argue (Denotational) Semantics

One way to understand polymorphism is to have a good model for types. At first approximation types can be modeled as sets of values (strictly speaking, as shown by Reynolds, the set-theoretical model fails in the case of polymorphic lambda calculus, but there are ways around it).

The type Bool is a two-element set of True and False, Integer is a set of integers, and so on. Composite types can also be defined set-theoretically. For instance, a pair type is a cartesian product of two sets. A list of a is a set of lists with elements from the set a. A function type a->b is a set of functions between two sets.

For parametric polymorphism you need to first be able to define functions on types: functions that take a type and produce a new type. In other words, you should be able to define a family of types that is parametrized by another type. In Haskell, we call such things type constructors.

For instance, given some type a, produce a type of pairs: (a, a). This can be formally written (not in Haskell) as:

Λa . (a, a)

Notice the capital lambda for defining functions on types (sets), as opposed to the lowercase lambda used for functions on values (set elements).

To turn a family of types into a family of values — a polymorphic value — you put the universal quantifier forall in front of it. Don’t read too much into the quantifier aspect of it — it makes sense in the Curry-Howard isomorphism, but here it’s just a piece of syntax. It means that you use the type constructor to pick a type, and then you pick a specific value of that type.

You may recall the Axiom of Choice (AoC) from set theory. This axiom says that if you have a set of sets then there always exists a set of samples created by picking one element from each set. It’s like going to a chocolate store and ordering one of each. It’s a controversial axiom, and mathematicians are very careful in either using or avoiding it. The controversy is that, for infinite sets of sets, there may be no constructive way of picking elements. And in computer science we are not so much interested in proofs of existence, as in actual algorithms that produce tangible results.

Here’s an example:

forall a . (a, a)

This is a valid type signature, but you’d be hard pressed to implement it. You’d have to provide a pair of concrete values for every possible type. You can’t do it uniformly across all types. (Especially that some types are uninhabited, as Gershom Bazerman kindly pointed out to me.)

Interestingly enough, you can sometimes define polymorphic values if you constrain polymorphism to certain typeclasses. For instance, when you define a numeric constant in Haskell:

x = 1

its type is polymorphic:

x :: forall a. Num a => a

(using the language extension ExplicitForAll). Here x represents a whole family of values, including:

1.0 :: Float 1 :: Int 1 :: Integer

with potentially different representations.

But there are some types of values that can be specified wholesale. These are function values. Functions are first class values in Haskell (although you can’t compare them for equality). And with one formula you can define a whole family of functions. The following signature, for instance, is perfectly implementable:

forall a . a -> a

Let’s analyze it. It consists of a type function, or a type constructor:

Λa . a -> a

which, for any type a, returns a function type a->a. When universally quantified with forall, it becomes a family of concrete functions, one per each type. This is possible because all these functions can be defined with one closed term (see Appendix 2). Here’s this term:

\x -> x

In this case we actually have a constructive way of picking one element — a function — for each type a. For instance, if a is a String, we pick a function that takes any String and returns the same string. It’s a particular String->String function, one of many possible String->String functions. And it’s different from the Int->Int function that takes an Int and returns the same Int. But all these identity functions are encoded using the same lambda expression. It’s that generic formula that allows us to chose a representative function from each set of functions a->a: one from the set String->String, one from the set Int->Int, etc.

In Haskell, we usually omit the forall quantifier when there’s no danger of confusion. Any signature that contains a type variable is automatically universally quantified over it. (You’ll have to use explicit forall, however, with higher-order polymorphism, where a polymorphic function can be passed as an argument to another function.)

So what’s the set-theoretic model for polymorphism? You simply replace types with sets. A function on types becomes a function on sets. Notice that this is not the same as a function between sets. The latter assigns elements of one set to elements of another. The former assigns sets to sets — you could call it a set constructor. As in: Take any set a and return a cartesian product of this set with itself.

Or take any set a and return the set of functions from this set to itself. We have just seen that for this one we can easily build a polymorphic function — one which for every type a produces an actual function whose type is (a->a). Now, with ad-hoc polymorphism it’s okay to code the String function separately from the Int function; but in parametric polymorphism, you’ll have to use the same code for all types.

This uniformity — one formula for all types — dramatically restricts the set of polymorphic functions, and is the source of free theorems.

Any language that provides some kind of pattern-matching on types (e.g., template specialization in C++) automatically introduces ad-hoc polymorphism. Ad-hoc polymorphism is also possible in Haskell through the use of type classes and type families.

Preservation of Relations

Let’s go to our original example and rewrite it using the explicit universal quantifier:

r :: forall a. [a] -> [a]

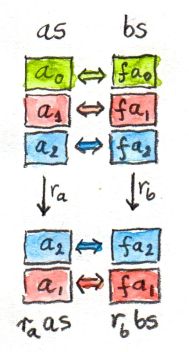

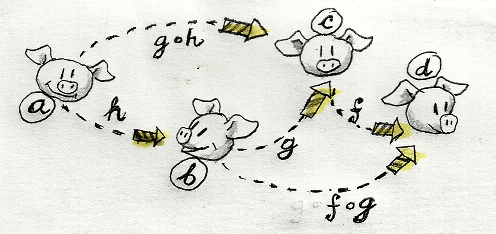

It defines a family of functions parametrized by the type a. When used in Haskell code, a particular member of this family will be picked automatically by the type inference system, depending on the context. In what follows, I’ll use explicit subscripting for the same purpose. The free theorem I mentioned before can be rewritten as:

rb (map f as) = map f (ra as)

with the function:

f :: a -> b

serving as a bridge between the types a and b. Specifically, f relates values of type a to values of type b. This relation happens to be functional, which means that there is only one value of type b corresponding to any given value of type a.

But the correspondence between elements of two lists may, in principle, be more general. What’s more general than a function? A relation. A relation between two sets a and b is defined as a set of pairs — a subset of the cartesian product of a and b. A function is a special case of a relation, one that can be represented as a set of pairs of the form (x, f x), or in relational notation x <=> f x. This relation is often called the graph of the function, since it can be interpreted as coordinates of points on a 2-d plane that form the plot the function.

The key insight of Reynolds was that you can abstract the shape of a data structure by defining relations between values. For instance, how do we know that two pairs have the same shape — even if one is a pair of integers, say (1, 7), and the other a pair of colors, say (Red, Blue)? Because we can relate 1 to Red and 7 to Blue. This relation may be called: “occupying the same position”.

Notice that the relation doesn’t have to be functional. The pair (2, 2) can be related to the pair (Black, White) using the non-functional relation:

(2 <=> Black), (2 <=> White)

This is not a function because 2 is not mapped to a single value.

Conversely, given any relation between integers and colors, you can easily test which integer pairs are related to which color pairs. For the above relation, for instance, these are all the pairs that are related:

((2, 2) <=> (Black, Black)), ((2, 2) <=> (Black, White)), ((2, 2) <=> (White, Black)), ((2, 2) <=> (White, White))

Thus a relation between values induces a relation between pairs.

This idea is easily extended to lists. Two lists are related if their corresponding elements are related: the first element of one list must be related to the first element of the second list, etc.; and empty lists are always related.

In particular, if the relationship between elements is established by a function f, it’s easy to convince yourself that the lists as and bs are related if

bs = map f as

With this in mind, our free theorem can be rewritten as:

rb bs = map f (ra as)

In other words, it tells us that the two lists

rb bs

and

ra as

are related through f.

So r transforms related lists into related lists. It may change the shape of the list, but it never touches the values in it. When it acts on two related lists, it rearranges them in exactly the same way, without breaking any of the relations between corresponding elements.

Reading Types as Relations

The above examples showed that we can define relations between values of composite types in terms of relations between values of simpler types. We’ve seen this with the pair constructor and with the list constructor. Continuing this trend, we can state that two functions:

f :: a -> b

and

g :: a' -> b'

are related iff, for related x and y, f x is related to g y. In other words, related functions map related arguments to related values.

Notice what we are doing here: We are consistently replacing types with relations in type constructors. This way we can read complex types as relations. The type constructor -> acts on two types, a and b. We extend it to act on relations: The “relation constructor” -> in A->B takes two relations A (between a and a') and B (between b and b') and produces a relation between functions f and g.

But what about primitive types? Let’s consider an example. Two functions from lists to integers that simply calculate the lengths of the lists:

lenStr :: [Char] -> Int lenBool :: [Bool] -> Int

What happens when we call them with two related lists? The first requirement for lists to be related is that they are of equal length. So when called with related lists the two functions will return the same integer value . It makes sense for us to consider these two functions related because they don’t inspect the values stored in the lists — just their shapes. (They also look like components of the same parametrically polymorphic function, length.)

It therefore makes sense to read a primitive type, such as Int, as an identity relation: two values are related if they are equal. This way our two functions, lenStr and lenBool are indeed related, because they turn related lists to related (equal) results.

Notice that for non-polymorphic functions the relationship that follows from their type is pretty restrictive. For instance, two functions Int->Int are related if and only if their outputs are equal for equal inputs. In other words, the functions must be (extensionally) equal.

All these relations are pretty trivial until we get to polymorphic functions. The type of a polymorphic function is specified by universally quantifying a function on types (a type constructor).

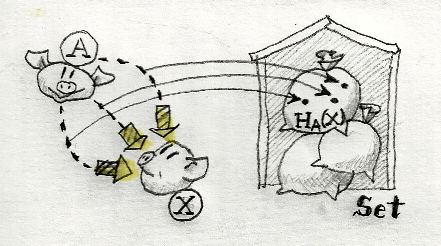

f :: forall a. φa

The type constructor φ maps types to types. In our set-theoretical model it maps sets to sets, but we want to read it in terms of relations.

Functions on relations

A general relation is a triple: We have to specify three sets, a, a', and a set of pairs — a subset of the cartesian product a × a'. It’s not at all obvious how to define functions that map relations to relations. What Reynolds chose is a definition that naturally factorizes into three mappings of sets, or to use the language of programming, three type constructors.

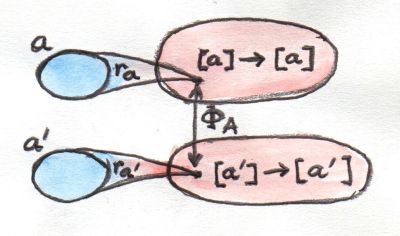

First of all, a function on relations Φ (or a “relation constructor”) is defined by two type constructors, φ and ψ. When Φ acts on a relation A between sets a and a', it first maps those sets, so that b=φa and b'=ψa'. ΦA then establishes a relation between the sets b and b'. In other words, ΦA is a subset of b × b'.

Fig 2. Φ maps relations to relations. The squarish sets represent cartesian products (think of a square as a cartesian product of two segments). Relations A and ΦA are subsets of these products.

Relations between polymorphic functions

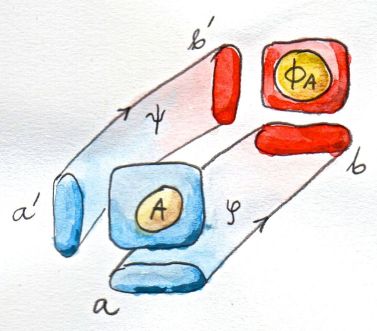

Given that Φ maps relations to relations, a universally quantified version of it:

forall A. ΦA

maps pairs of sets to pairs of values.

Now suppose that you have two polymorphic functions g and g':

g :: forall a . φa g' :: forall a'. ψa'

They both map types (sets) to values.

- We can instantiate

gat some typea, and it will return a valuegaof the typeb=φa. - We can instantiate

g'at some typea', and it will return a valueg'a'of the typeb'=ψa'.

We can do this for any relation A between two arbitrary sets a and a'.

We will say that g and g' are related through the relation induced by the type (forall A. ΦA) iff the results ga and g'a' are related by ΦA.

Fig 3. Relation between two polymorphic functions. The pair (g a, g' a') falls inside the relation ΦA.

In other words, polymorphic functions are related if they map related types to related values. Notice that in the interesting examples these values are themselves functions.

With these definitions, we can now reinterpret any type signature as a relation between values.

The Parametricity Theorem

Reynolds’ second key insight was that any term is in a relation with itself — the relation being induced by the term’s type. We have indeed defined the mapping of types to relations to make this work. Primitive types turn into identity relations, so obviously a primitive value is in relation with itself. A function between primitive types is in relation with itself because it maps related (equal) arguments into related (equal) results. A list or a pair of primitive types is in relation with itself because each element of it is equal to itself. You can recurse and consider a list of functions, or a pair of lists, etc., building the proof inductively, proceeding from simpler types to more and more complex types. The proof goes over all possible term construction rules and typing rules in a given theory.

Formally, this kind of proof is called “structural induction,” because you’re showing that more complex structures will satisfy the theorem as long as the simpler ones, from which they are constructed, do. The only tricky part is dealing with polymorphic functions, because they are quantified over all types (including polymorphic types). In fact, this is the reason why the naive interpretation of types as sets breaks down (see, however, Pitts’ paper). It is possible, however, to prove the parametricity theorem in a more general setting, for instance, using frames, or in the framework of operational semantics, so we won’t worry about it here.

Wadler’s key insight was to interpret Reynolds’ theorem not only as a way of identifying different implementations of the same type — for instance, cartesian and polar representations of complex numbers — but also as a source of free theorems for polymorphic types.

Let’s try applying parametricity theorem to some simple examples. Take a constant term: an integer like 5. Its type Int can be interpreted as a relation, which we defined to be the identity relation (it’s one of the primitive types). And indeed, 5 is in this relation with 5.

Take a function like:

ord :: Char -> Int

Its type defines a relation between functions: Two functions of the type Char->Int are related if they return equal integers for equal characters. Obviously, ord is in this relation with itself.

Parametricity in Action

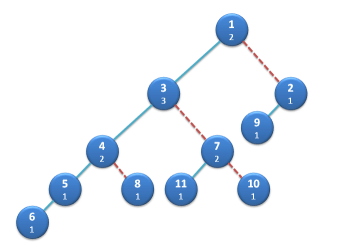

Those were trivial examples. The interesting ones involve polymorphic functions. So let’s go back to our starting example. The term now is the polymorphic function r whose type is:

r :: forall a . [a] -> [a]

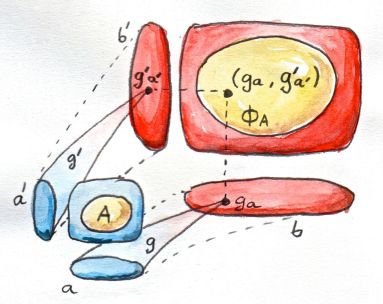

Parametricity tells us that r is in relation with itself. However, comparing a polymorphic function to itself involves comparing the instantiations of the same function at two arbitrary types, say a and a'. Let’s go through this example step by step.

We are free to pick an arbitrary relation A between elements of two arbitrary input sets a and a'. The type of r induces a mapping Φ on relations. As with every function on relations, we have to first identify the two type constructors φ and ψ, one mapping a and one mapping a'. In our case they are identical, because they are induced by the same polymorphic function. They are equal to:

Λ a. [a]->[a]

It’s a type constructor that maps an arbitrary type a to the function type [a]->[a].

The universal quantifier forall means that r lets us pick a particular value of the type [a]->[a] for each a. This value is a function that we call ra. We don’t care how this function is picked by r, as long as it’s picked uniformly, using a single formula for all a, so that our parametricity theorem holds.

Fig 4. Polymorphic function r maps related types to related values, which themselves are functions on lists

Parametricity means that, if a is related to a', then:

ra <=> ra'

This particular relation is induced by the function type [a]->[a]. By our definition, two functions are related if they map related arguments to related results. In this case both the arguments and the results are lists. So if we have two related lists, as and as':

as :: [a] as' :: [a']

they must, by parametricity, be mapped to two related lists, bs and bs':

bs = ra as bs' = ra' as'

This must be true for any relation A, so let’s pick a functional relation generated by some function:

f :: a -> a'

This relation induces a relation on lists:

as' = map f as

The results of applying r, therefore, must be related through the same relation:

bs' = map f bs

Combining all these equalities, we get our expected result:

ra' (map f as) = map f (ra as)

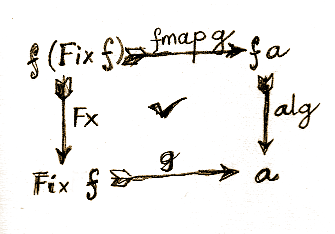

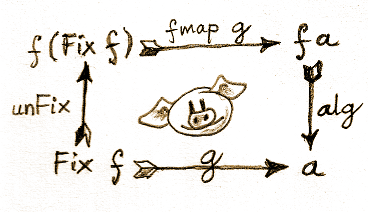

Parametricity and Natural Transformations

The free theorem I used as the running example is interesting for another reason: The list constructor is a functor. You may think of functors as generalized containers for storing arbitrary types of values. You can imagine that they have shapes; and for two containers of the same shape you may establish a correspondence between “positions” at which the elements are stored. This is quite easy for traditional containers like lists or trees, and with a leap of faith it can be stretched to non-traditional “containers” like functions. We used the intuition of relations corresponding to the idea of “occupying the same position” within a data structure. This notion can be readily generalized to any polymorphic containers. Two trees, for instance, are related if they are both empty, or if they have the same shape and their corresponding elements are related.

Let’s try another functor: You can also think of Maybe as having two shapes: Nothing and Just. Two Nothings are always related, and two Justs are related if their contents are related.

This observation immediately gives us a free theorem about polymorphic functions of the type:

r :: forall a. [a] -> Maybe a

an example of which is safeHead. The theorem is:

fmap h . safeHead == safeHead . fmap h

Notice that the fmap on the left is defined by the Maybe functor, whereas the one on the right is the list one.

If you accept the premise that an appropriate relation can be defined for any functor, then you can derive a free theorem for all polymorphic functions of the type:

r :: forall a. f a -> g a

where f and g are functors. This type of function is known as a natural transformation between the two functors, and the free theorem:

fmap h . r == r . fmap h

is the naturality condition. That’s how naturality follows from parametricity.

Acknowledgments

I’d like to thank all the people I talked to about parametricity at the ICFP in Gothenburg, and Edward Kmett for reading and commenting on the draft of this blog.

Appendix 1: Other Examples

Here’s a list of other free theorems from Wadler’s paper. You might try proving them using parametricity.

r :: [a] -> a -- for instance, head f . r == r . fmap f

r :: [a] -> [a] -> [a] -- for instance, (++) fmap f (r as bs) == r (fmap f as) (fmap f bs)

r :: [[a]] -> [a] -- for instance, concat fmap f . r == r . fmap (fmap f)

r :: (a, b) -> a -- for instance, fst f . r == r . mapPair (f, g)

r :: (a, b) -> b -- for instance, snd g . r == r . mapPair (f, g)

r :: ([a], [b]) -> [(a, b)] -- for instance, uncurry zip fmap (mapPair (f, g)) . r == r . mapPair (fmap f, fmap g)

r :: (a -> Bool) -> [a] -> [a] -- for instance, filter fmap f . r (p . f) = r p . fmap f

r :: (a -> a -> Ordering) -> [a] -> [a] -- for instance, sortBy -- assuming: f is monotone (preserves order) fmap f . r cmp == r cmp' . fmap f

r :: (a -> b -> b) -> b -> [a] -> b -- for instance, foldl -- assuming: g (acc x y) == acc (f x) (g y) g . foldl acc zero == foldl acc (g zero) . fmap f

r :: a -> a -- id f . r == r . f

r :: a -> b -> a -- for instance, the K combinator f (r x y) == r (f x) (g y)

where:

mapPair :: (a -> c, b -> d) -> (a, b) -> (c, d) mapPair (f, g) (x, y) = (f x, g y)

Appendix 2: Identity Function

Let’s prove that there is only one polymorphic function of the type:

r :: forall a. a -> a

and it’s the identity function:

id x = x

We start by picking a particular relation. It’s a relation between the unit type () and an arbitrary (inhabited) type a. The relation consists of just one pair ((), c), where () is the unit value and c is an element of a. By parametricity, the function

r() :: () -> ()

must be related to the function

ra :: a -> a

There is only one function of the type ()->() and it’s id(). Related functions must map related argument to related values. We know that r() maps unit value () to unit value (). Therefore ra must map c to c. Since c is arbitrary, ra must be an identity for all (inhabited) as.

Bibliography

- John C Reynolds, Types, Abstraction and Parametric Polymorphism

- Philip Wadler, Theorems for Free!

- Claudio Hermida, Uday S. Reddy, Edmund P. Robinson, Logical Relations and Parametricity – A Reynolds Programme for Category Theory and Programming Languages

- Derek Dreyer, Paremetricity and Relational Reasoning, Oregon Programming Languages Summer School

- Janis Voigtländer, Free Theorems Involving Type Constructor Classes