For an outsider, Haskell is full of intimidating terms like functor, monad, applicative, monoid… These mathematical abstractions are hard to explain to a newcomer. The internet is full of tutorials that try to simplify them with limited success.

The most common simplification you hear is that a functor or a monad is like a box or a container. Indeed, a list is a container and a functor, Maybe is like a box, but what about functions? Functions from a fixed type to an arbitrary type define both a functor and a monad (the reader monad). More complex functions define the state and the continuation monads (all these monads are functors as well). I used to point these out as counterexamples to the simplistic picture of a functor as a container. Then I had an epiphany: These are containers!

So here’s the plan: I will first try to convince you that a functor is the purest expression of containment. I’ll follow with progressively more complex examples. Then I’ll show you what natural transformations really are and how simple the Yoneda lemma is in terms of containers. After functors, I’ll talk about container interpretation of pointed, applicative, and monad. I will end with a new twist on the state monad.

What’s a Container?

What is a container after all? We all have some intuitions about containers and containment but if you try to formalize them, you get bogged down with tricky cases. For instance, can a container be infinite? In Haskell you can easily define the list of all integers or all Pythagorean triples. In non-lazy language like C++ you can fake infinite containers by defining input iterators. Obviously, an infinite container doesn’t physically contain all the data: it generates it on demand, just like a function does. We can also memoize functions and tabulate their values. Is the hash table of the values of the sin function a container or a function?

The bottom line is that there isn’t that much of a difference between containers and functions.

What characterizes a container is its ability to contain values. In a strongly typed language, these values have types. The type of elements shouldn’t matter, so it’s natural to describe a generic container as a mapping of types — element type to container type. A truly polymorphic container should not impose any constraints on the type of values it contains, so it is a total function from types to types.

It would be nice to be able to generically describe a way to retrieve values stored in a container, but each container provides its own unique retrieval protocol. A retrieval mechanism needs a way to specify the location from which to retrieve the value and a protocol for failure. This is an orthogonal problem and, in Haskell, it is addressed by lenses.

It would also be nice to be able to iterate over, or enumerate the contents of a container, but that cannot be done generically either. You need at least to specify the order of traversal. Even the simplest list can be traversed forwards or backwards, not to mention pre-, in-, and post-order traversals of trees. This problem is addressed, for instance, by Haskell’s Traversable functors.

But I think there is a deeper reason why we wouldn’t want to restrict ourselves to enumerable containers, and it has to do with infinity. This might sound like a heresy, but I don’t see any reason why we should limit the semantics of a language to countable infinities. The fact that digital computers can’t represent infinities, even those of the countable kind, doesn’t stop us from defining types that have infinite membership (the usual Ints and Floats are finite, because of the binary representation, but there are, for instance, infinitely many lists of Ints). Being able to enumerate the elements of a container, or convert it to a (possibly infinite) list means that it is countable. There are some operations that require countability: witness the Foldable type class with its toList function and Traversable, which is a subclass of Foldable. But maybe there is a subset of functionality that does not require the contents of the container to be countable.

If we restrain ourselves from retrieving or enumerating the contents of a container, how do we know the contents even exists? Because we can operate on it! The most generic operation over the contents of a container is applying a function to it. And that’s what functors let us do.

Container as Functor

Here’s the translation of terms from category theory to Haskell.

A functor maps all objects in one category to objects in another category. In Haskell the objects are types, so a functor maps types into types (so, strictly speaking, it’s an endofunctor). You can look at it as a function on types, and this is reflected in the notation for the kind of the functor: * -> *. But normally, in a definition of a functor, you just see a polymorphic type constructor, which doesn’t really look like a function unless you squint really hard.

A categorical functor also maps morphisms to morphisms. In Haskell, morphisms correspond to functions, so a Functor type class defines a mapping of functions:

fmap :: (a -> b) -> (f a -> f b)

(Here, f is the functor in question acting on types a and b.)

Now let’s put on our container glasses and have another look at the functor. The type constructor defines a generic container type parameterized by the type of the element. The polymorphic function fmap, usually seen in its curried form:

fmap :: (a -> b) -> f a -> f b

defines the action of an arbitrary function (a -> b) on a container (f a) of elements of type a resulting in a container full of elements of type b.

Examples

Let’s have a look at a few important functors as containers.

There is the trivial but surprisingly useful container that can hold no elements. It’s called the Const functor (parameterized by an unrelated type b):

newtype Const b a = Const { getConst :: b }

instance Functor (Const b) where

fmap _ (Const x) = Const x

Notice that fmap ignores its function argument because there isn’t any contents this function could act upon.

A container that can hold one and only one element is defined by the Identity functor:

newtype Identity a = Identity { runIdentity :: a }

instance Functor Identity where

fmap f (Identity x) = Identity (f x)

Then there is the familiar Maybe container that can hold (maybe) one element and a bunch of regular containers like lists, trees, etc.

The really interesting container is defined by the function application functor, ((->) e) (which I would really like to write as (e-> )). The functor itself is parameterized by the type e — the type of the function argument. This is best seen when this functor is re-cast as a type constructor:

newtype Reader e a = Reader (e -> a)

This is of course the functor that underlies the Reader monad, where the first argument represents some kind of environment. It’s also the functor you’ll see in a moment in the Yoneda lemma.

Here’s the Functor instance for Reader:

instance Functor (Reader e) where

fmap f (Reader g) = Reader (\x -> f (g x))

or, equivalently, for the function application operator:

instance Functor ((->) e) where

fmap = (.)

This is a strange kind of container where the values that are “stored” are keyed by values of type e, the environments. Given a particular environment, you can retrieve the corresponding value by simply calling the function:

runReader :: Reader e a -> e -> a runReader (Reader f) env = f env

You can look at it as a generalization of the key/value store where the environment plays the role of the key.

The reader functor (for the lack of a better term) covers a large spectrum of containers depending of the type of the environment you pick. The simplest choice is the unit type (), which contains only one element, (). A function from unit is just a constant, so such a function provides a container for storing one value (just like the Identity functor). A function of Bool stores two values. A function of Integer is equivalent to an infinite list. If it weren’t for space and time limitations we could in principle memoize any function and turn it into a lookup table.

In type theory you might see the type of functions from A to B written as BA, where A and B are types seen as sets. That’s because the analogy with exponentiation — taking B to the power of A — is very fruitful. When A is the unit type with just one element, BA becomes B1, which is just B: A function from unit is just a constant of type B. A function of Bool, which contains just two elements, is like B2 or BxB: a Cartesian product of Bs, or the set of pairs of Bs. A function from the enumeration of N values is equivalent to an N-tuple of Bs, or an element of BxBxBx…B, N-fold. You can kind of see how this generalizes into B to the power of A, for arbitrary A.

So a function from A to B is like a huge tuple of Bs that is indexed by an element of A. Notice however that the values stored in this kind of container can only be enumerated (or traversed) if A itself is enumerable.

The IO functor that is the basis of the IO monad is even more interesting as a container because it offers no way of extracting its contents. An object of the type IO String, for instance, may contain all possible answers from a user to a prompt, but we can’t look at any of them in separation. All we can do is to process them in bulk. This is true even when IO is looked upon as a monad. All a monad lets you do is to pass your IO container to another monadic function that returns a new container. You’re just passing along containers without ever finding out if the Schrodinger’s cat trapped in them is dead or alive. Yes, parallels with quantum mechanics help a lot!

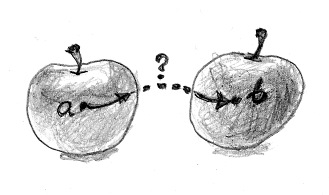

Natural Transformations

Now that we’ve got used to viewing functors as containers, let’s figure out what natural transformations are. A natural transformation is a mapping of functors that preserves their functorial nature. If functor F maps object A to X and another functor G maps A to Y, then a natural transformation from F to G must map X to Y. A mapping from X to Y is a morphism. So you can look at a natural transformation as a family of morphisms parameterized by A.

In Haskell, we turn all these objects A, X, and Y into types. We have two functors f and g acting on type a. A natural transformation will be a polymorphic function that maps f a to g a for any a.

forall a . f a -> g a

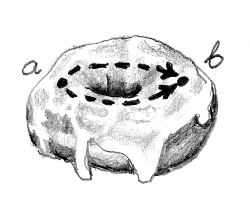

What does it mean in terms of containers? Very simple: A natural transformation is a way of re-packaging containers. It tells you how to take elements from one container and put them into another. It must do it without ever inspecting the elements themselves (it can, however, drop some elements or clone them).

Examples of natural transformations abound, but my favorite is safeHead. It takes the head element from a list container and repackages it into a Maybe container:

safeHead :: forall a . [a] -> Maybe a safeHead [] = Nothing safeHead (x:xs) = Just x

What about a more ambitions example: Let’s take a reader functor, Int -> a, and map it into the list functor [a]. The former corresponds to a container of a keyed by an integer, so it’s easily repackaged into a finite or an infinite list, for instance:

genInfList :: forall a . (Int -> a) -> [a] genInfList f = fmap f [0..]

I’ll show you soon that all natural transformations from (Int -> a) to [a] have this form, and differ only by the choice of the list of integers (here, I arbitrarily picked [0..]).

A natural transformation, being a mapping of functors, must interact nicely with morphisms as well. The corresponding naturality condition translates easily into our container language. It tells you that it shouldn’t matter whether you first apply a function to the contents of a container (fmap over it) and then repackage it, or first repackage and then apply the function. This meshes very well with our intuition that repackaging doesn’t touch the elements of the container — it doesn’t breaks the eggs in the crate.

The Yoneda Lemma

Now let’s get back to the function application functor (the Reader functor). I said it had something to do with the Yoneda lemma. I wrote a whole blog about the Yoneda lemma, so I’m not going to repeat it here — just translate it into the container language.

What Yoneda says is that the reader is a universal container from which stuff can be repackaged into any other container. I just showed you how to repackage the Int reader into a list using fmap and a list of Int. It turns out that you can do the same for any type of reader and an arbitrary container type. You just provide a container full of “environments” and fmap the reader function over it. In my example, the environment type was Int and the container was a list.

Moreover, Yoneda says that there is a one-to-one correspondence between “repackaging schemes” and containers of environments. Given a container of environments you do the repackaging by fmapping the reader over it, as I did in the example. The inverse is also easy: given a repackaging, call it with an identity reader:

idReader :: Reader e e idReader = Reader id

and you’ll get a container filled with environments.

Let me re-word it in terms of functors and natural transformations. For any functor f and any type e, all natural transformations of the form:

forall a . ((e -> a) -> f a)

are in one-to-one correspondence with values of the type f e. This is a pretty powerful equivalence. On the one hand you have a polymorphic function, on the other hand a polymorphic data structure, and they encode the same data. Except that things you do with functions are different than things you do with data structures so, depending on the context, one may be more convenient than the other.

For instance, if we apply the Yoneda lemma to the reader functor itself, we find out that all repackagings (natural transformations) between readers can be parameterized by functions between their environment types:

forall a . ((e -> a) -> (e' -> a)) ~ e' -> e

Or, you can look at this result as the CPS transform: Any function can be encoded in the Continuation Passing Style. The argument (e -> a) is the continuation. The forall quantifier tells us that the return type of the continuation is up to the caller. The caller might, for instance, decide to print the result, in which case they would call the function with the continuation that returns IO (). Or they might call it with id, which is itself polymorphic: a -> a.

Where Do Containers Come From?

A functor is a type constructor — it operates on types — but in a program you want to deal with data. A particular functor might define its data constructor: List and Maybe have constructors. A function, which we need in order to create an instance of the reader functor, may either be defined globally or through a lambda expression. You can’t construct an IO object, but there are some built-in runtime functions, like getChar or putChar that return IO.

If you have functions that produce containers you may compose them to create more complex containers, as in:

-- m is the functor f :: a -> m b g :: b -> m c fmap g (f x) :: m (m c)

But the general ability to construct containers from scratch and to combine them requires special powers that are granted by successively more powerful classes of containers.

Pointed

The first special power is the ability to create a default container from an element of any type. The function that does that is called pure in the context of applicative and return in the context of a monad. To confuse things a bit more, there is a type class Pointed that defines just this ability, giving it yet another name, point:

class Functor f => Pointed f where

point :: a -> f a

point is a natural transformation. You might object that there is no functor on the left hand side of the arrow, but just imagine seeing Identity there. Naturality just means that you can sneak a function under the functor using fmap:

fmap g (point x) = point (g x)

The presence of point means that there is a default, “trivial,” shape for the container in question. We usually don’t want this container to be empty (although it may — I’m grateful to Edward Kmett for correcting me on this point). It doesn’t mean that it’s a singleton, though — for ZipList, for instance, pure generates an infinite list of a.

Applicative

Once you have a container of one type, fmap lets you generate a container of another type. But since the function you pass to fmap takes only one argument, you can’t create more complex types that take more than one argument in their constructor. You can’t even create a container of (non-diagonal) pairs. For that you need a more general ability: to apply a multi-argument function to multiple containers at once.

Of course, you can curry a multi-argument function and fmap it over the first container, but the result will be a container of hungry functions waiting for more arguments.

h :: a -> b -> c fmap h (m a) :: m (b -> c)

(Here, m stands for the functor, applicative, or the monad in question.)

What you need is the ability to apply a container of functions to a container of arguments. The function that does that is called <*> in the context of applicative, and ap in the context of monad.

(<*>) :: m (a -> b) -> m a -> m b

As I mentioned before, Applicative is also Pointed, with point renamed to pure. This lets you wrap any additional arguments to your multi-argument functions.

The intuition is that applicative brings to the table its ability to increase the complexity of objects stored in containers. A functor lets you modify the objects but it’s a one-input one-output transformation. An applicative can combine multiple sources of information. You will often see applicative used with data constructors (which are just functions) to create containers of object from containers of arguments. When the containers also carry state, as you’ll see when we talk about State, an applicative will also be able to reflect the state of the arguments in the state of the result.

Monad

The monad has the special power of collapsing containers. The function that does it is called join and it turns a container of containers into a single container:

join :: m (m a) -> m a

Although it’s not obvious at first sight, join is also a natural transformation. The fmap for the m . m functor is the square of the original fmap, so the naturality condition looks like this:

fmap f . join = join . (fmap . fmap) f

Every monad is also an applicative with return playing the role of pure and ap implementing <*>:

ap :: m (a -> b) -> m a -> m b ap mf ma = join $ fmap (\f -> fmap f ma) mf

When working with the container interpretation, I find this view of a monad as an applicative functor with join more intuitive. In practice, however, it’s more convenient to define the monad in terms of bind, which combines application of a function a la fmap with the collapsing of the container. This is done using the function >>=:

(>>=) :: m a -> (a -> m b) -> m b ma >>= k = join (fmap k ma)

Here, k is a function that produces containers. It is applied to a container of a, ma, using fmap. We’ve seen this before, but we had no way to collapse the resulting container of containers — join makes this possible.

Imagine a hierarchy of containment. You start with functions that produce containers. They “lift” your data to the level of containers. These are functions like putChar, data constructors like Just, etc. Then you have the “trivial” lifters of data called pure or return. You may operate on the data stored in containers by “lifting” a regular function using fmap. Applicative lets you lift multi-parameter functions to create containers of more complex data. You may also lift functions that produce containers to climb the rungs of containment: you get containers of containers, and so on. But only the monad provides the ability to collapse this hierarchy.

State

Let’s have a look at the state functor, the basis of the state monad. It’s very similar to the reader functor, except that it also modifies the environment. We’ll call this modifiable environment “state.” The modified state is paired with the return value of the function that defines the state functor:

newtype State s a = State (s -> (a, s))

As a container, the reader functor generalized the key/value store. How should we interpret the state functor in the container language? Part of it is still the key/value mapping, but we have the additional key/key mapping that describes the state transformation. (The state plays the role of the key.) Notice also that the action of fmap modifies the values, but doesn’t change the key mappings.

instance Functor (State s) where

fmap f (State g) = State (\st -> let (x, st') = g st

in (f x, st'))

This is even more obvious if we separate the two mappings. Here’s the equivalent definition of the state functor in terms of two functions:

data State' s a = State' (s -> a) (s -> s)

The first function maps state to value: that’s our key/value store, identical to that of the reader functor. The second function is the state transition matrix. Their actions are quite independent:

runState' (State' f tr) s = (f s, tr s)

In this representation, you can clearly see that fmap only acts on the key/value part of the container, and its action on data is identical to that of the reader functor:

instance Functor (State' s) where fmap f (State' g tr) = State' (f . g) tr

In the container language, we like to separate the contents from the shape of the container. Clearly, in the case of the state functor, the transition matrix, not being influenced by fmap, is part of the shape.

A look at the Applicative instance for this representation of the state functor is also interesting:

instance Applicative (State' s) where

pure x = State' (const x) id

State' fg tr1 <*> State' fx tr2 =

State' ff (tr2 . tr1)

where

ff st = let g = fg st

x = fx (tr1 st)

in g x

The default container created by pure uses identity as its transition matrix. As expected, the action of <*> creates a new “shape” for the container, but it does it in a very regular way by composing the transition matrices. In the language of linear algebra, the transformation of state by the applicative functor would be called “linear.” This will not be true with monads.

You can also see the propagation of side effects: the values for the first and second argument are retrieved using different keys: The key for the retrieval of the function g is the original state, st; but the argument to the function, x, is retrieved using the state transformed by the transition matrix of the first argument (tr1 st). Notice however that the selection of keys is not influenced by the values stored in the containers.

But here’s the monad instance:

instance Monad (State' s) where

return x = State' (const x) id

State' fx tr >>= k =

State' ff ttr

where

ff st = let x = fx st

st' = tr st

State' fy tr' = k x

in fy st'

ttr st = let x = fx st

st' = tr st

State' fy tr' = k x

in tr' st'

What’s interesting here is that the calculation of the transition matrix requires the evaluation of the function k with the argument x. It means that the state transition is no longer linear — the decision which state to chose next may depend on the contents of the container. This is also visible in the implementation of join for this monad:

join :: State' s (State' s a) -> State' s a

join (State' ff ttr) = State' f' tr'

where

f' st = let State' f tr = ff st

st' = ttr st

in f st'

tr' st = let State' f tr = ff st

st' = ttr st

in tr st'

Here, the outer container stores the inner container as data. Part of the inner container is its transition matrix. So the decision of which transition matrix tr to use is intertwined with data in a non-linear way.

This non-linearity means that a monad is strictly more powerful than applicative, but it also makes composing monads together harder.

Conclusions

The only way to really understand a complex concept is to see it from as many different angles as possible. Looking at functors as containers provides a different perspective and brings new insights. For me it was the realization that functions can be seen as non-enumerable containers of values, and that the state monad can be seen as a key/value store with an accompanying state transition matrix that brought the aha! moments. It was also nice to explicitly see the linearity in the applicative’s propagation of state. It was surprising to discover the simplicity of the Yoneda lemma and natural transformations in the language of containers.

Bibliography and Acknowledgments

A container is not a very well defined term — an ambiguity I exploited in this blog post — but there is a well defined notion of finitary containers, and they indeed have a strong connection to functors. Russell O’Connor and Mauro Jaskelioff have recently shown that every traversable functor is a finitary container (I’m grateful to the authors for providing me with the preliminary copy of their paper, in which they have also independently and much more rigorously shown the connection between the Yoneda lemma for the functor category and the van Laarhoven formulation of the lens).