The yearly Advent of Code is always a source of interesting coding challenges. You can often solve them the easy way, or spend days trying to solve them “the right way.” I personally prefer the latter. This year I decided to do some yak shaving with a puzzle that involved looking for patterns in a grid. The pattern was the string XMAS, and it could start at any location and go in any direction whatsoever.

My immediate impulse was to elevate the grid to a comonad. The idea is that a comonad describes a data structure in which every location is a center of some neighborhood, and it lets you apply an algorithm to all neighborhoods in one fell swoop. Common examples of comonads are infinite streams and infinite grids.

Why would anyone use an infinite grid to solve a problem on a finite grid? Imagine you’re walking through a neighborhood. At every step you may hit the boundary of a grid. So a function that retrieves the current state is allowed to fail. You may implement it as returning a Maybe value. So why not pre-fill the infinite grid with Maybe values, padding it with Nothing outside of bounds. This might sound crazy, but in a lazy language it makes perfect sense to trade code for data.

I won’t bore you with the details, they are available at my GitHub repository. Instead, I will discuss a similar program, one that I worked out some time ago, but wasn’t satisfied with the solution: the famous Conway’s Game of Life. This one actually uses an infinite grid, and I did implement it previously using a comonad. But this time I was more ambitious: I wanted to generate this two-dimensional comonad by composing a pair of one-dimensional ones.

The idea is simple. Each row of the grid is an infinite bidirectional stream. Since it has a specific “current position,” we’ll call it a cursor. Such a cursor can be easily made into a comonad. You can extract the current value; and you can duplicate a cursor by creating a cursor of cursors, each shifted by the appropriate offset (increasing in one direction, decreasing in the other).

A two-dimensional grid can then be implemented as a cursor of cursors–the inner one extending horizontally, and the outer one vertically.

It should be a piece of cake to define a comonad instance for it: extract should be a composition of (extract . extract) and duplicate a composition of (duplicate . fmap duplicate), right? It typechecks, so it must be right. But, just in case, like every good Haskell programmer, I decided to check the comonad laws. There are three of them:

extract . duplicate = id fmap extract . duplicate = id duplicate . duplicate = fmap duplicate . duplicate

And they failed! I must have done something illegal, but what?

In cases like this, it’s best to turn to basics–which means category theory. Compared to Haskell, category theory is much less verbose. A comonad is a functor equipped with two natural transformations:

In Haskell, we write the components of these transformations as:

extract :: w a -> a duplicate :: w a -> w (w a)

The comonad laws are illustrated by the following commuting diagrams. Here are the two counit laws:

and one associativity law:

These are the same laws we’ve seen above, but the categorical notation makes them look more symmetric.

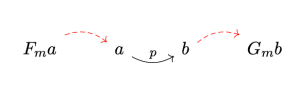

So the problem is: Given a comonad , is the composition

also a comonad? Can we implement the two natural transformations for it?

The straightforward implementation would be:

corresponding to (extract . extract), and:

corresponding to (duplicate . fmap duplicate).

To see why this doesn’t work, let’s ask a more general question: When is a composition of two comonads, say , again a comonad? We can easily define a counit:

The comultiplication, though, is tricky:

Do you see the problem? The result is but it should be

. To make it a comonad, we have to be able to push

through

in the middle. We need

to distribute over

through a natural transformation:

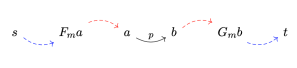

But isn’t that only relevant when we compose two different comonads–surely any functor distributes over itself! And there’s the rub: Not every comonad distributes over itself. Because a distributive comonad must preserve the comonad laws. In particular, to restore the the counit law we need this diagram to commute:

and for the comultiplication law, we require:

Even if the two comonad are the same, the counit condition is still non-trivial:

The two whiskerings of are in general not equal. All we can get from the original comonad laws is that they are only equal when applied to the result of comultiplication:

.

Equipped with the distributive mapping we can complete our definition of comultiplication for a composition of two comonads:

Going back to our Haskell code, we need to impose the distributivity condition on our comonad. There is a type class for it defined in Data.Distributive:

class Functor w => Distributive w where distribute :: Functor f => f (w a) -> w (f a)

Thus the general formula for composing two comonads is:

instance (Comonad w2, Comonad w1, Distributive w1) =>

Comonad (Compose w2 w1) where extract = extract . extract . getCompose duplicate = fmap Compose . Compose . fmap distribute . duplicate . fmap duplicate . getCompose

In particular, it works for composing a comonad with itself, as long as the comonad distributes over itself.

Equipped with these new tools, let’s go back to implementing a two-dimensional infinite grid. We start with an infinite stream:

data Stream a = (:>) { headS :: a

, tailS :: Stream a}

deriving Functor

infixr 5 :>

What does it mean for a stream to be distributive? It means that we can transpose a “matrix” whose rows are streams. The functor f is used to organize these rows. It could, for instance, be a list functor, in which case you’d have a list of (infinite) streams.

[ 1 :> 2 :> 3 .. , 10 :> 20 :> 30 .. , 100 :> 200 :> 300 .. ]

Transposing a list of streams means creating a stream of lists. The first row is a list of heads of all the streams, the second row is a list of second elements of all the streams, and so on.

[1, 10, 100] :> [2, 20, 200] :> [3, 30, 300] :> ..

Because streams are infinite, we end up with an infinite stream of lists. For a general functor, we use a recursive formula:

instance Distributive Stream where

distribute :: Functor f => f (Stream a) -> Stream (f a)

distribute stms = (headS stms) :> distribute (tailS stms)

(Notice that, if we wanted to transpose a list of lists, this procedure would fail. Interestingly, the list monad is not distributive. We really need either fixed size or infinity in the picture.)

We can build a cursor from two streams, one going backward to infinity, and one going forward to infinity. The head of the forward stream will serve as our “current position.”

data Cursor a = Cur { bwStm :: Stream a

, fwStm :: Stream a }

deriving Functor

Because streams are distributive, so are cursors. We just flip them about the diagonal:

instance Distributive Cursor where

distribute :: Functor f => f (Cursor a) -> Cursor (f a)

distribute fCur = Cur (distribute (bwStm fCur))

(distribute (fwStm fCur))

A cursor is also a comonad:

instance Comonad Cursor where

extract (Cur _ (a :> _)) = a

duplicate bi = Cur (iterateS moveBwd (moveBwd bi))

(iterateS moveFwd bi)

duplicate creates a cursor of cursors that are progressively shifted backward and forward. The forward shift is implemented as:

moveFwd :: Cursor a -> Cursor a moveFwd (Cur bw (a :> as)) = Cur (a :> bw) as

and similarly for the backward shift.

Finally, the grid is defined as a cursor of cursors:

type Grid a = Compose Cursor Cursor a

And because Cursor is a distributive comonad, Grid is automatically a lawful comonad. We can now use the comonadic extend to advance the state of the whole grid:

generations :: Grid Cell -> [Grid Cell] generations = iterate $ extend nextGen

using a local function:

nextGen :: Grid Cell -> Cell

nextGen grid

| cnt == 3 = Full

| cnt == 2 = extract grid

| otherwise = Empty

where

cnt = countNeighbors grid

You can find the full implementation of the Game of Life and the solution of the Advent of Code puzzle, both using comonad composition, on my GitHub.