This is my 100th WordPress post, so I decided to pull all the stops and go into some crazy stuff where hard math and hard physics mix freely with wild speculation. I hope you will enjoy reading it as much as I enjoyed writing it.

It’s a HoTT Summer of 2013

One of my current activities is reading the new book, Homotopy Type Theory (HoTT) that promises to revolutionize the foundations of mathematics in a way that’s close to the heart of a programmer. It talks about types in the familiar sense: Booleans, natural numbers, (polymorphic) function types, tuples, discriminated unions, etc.

As do previous type theories, HoTT assumes the Curry-Howard isomorphism that establishes the correspondence between logic and type theory. The gist of it is that any theorem can be translated into a definition of a type; and its proof is equivalent to producing a value of that type (false theorems correspond to uninhabited types that have no elements). Such proofs are by necessity constructive: you actually have to construct a value to prove a theorem. None if this “if it didn’t exist then it would lead to contradictions” negativity that is shunned by intuitionistic logicians. (HoTT doesn’t constrain itself to intuitionistic logic — too many important theorems of mathematics rely on non-constructive proofs of existence — but it clearly delineates its non-intuitionistic parts.)

Type theory has been around for some time, and several languages and theorem provers have been implemented on the base of the Curry-Howard isomorphism: Agda and Coq being common examples. So what’s new?

Set Theory Rant

Here’s the problem: Traditional type theory is based on set theory. A type is defined as a set of values. Bool is a two-element set {True, False}. Char is a set of all (Unicode) characters. String is an infinite set of all lists of characters. And so on. In fact all of traditional mathematics is based on set theory. It’s the “assembly language” of mathematics. And it’s not a very good assembly language.

First of all, the naive formulation of set theory suffers from paradoxes. One such paradox, called Russell’s paradox, is about sets that are members of themselves. A “normal” set is not a member of itself: a set of dogs is not a dog. But a set of all non-dogs is a member of itself — it’s “abnormal”. The question is: Is the set of all “normal” sets normal or abnormal? If it’s normal that it’s a member of normal sets, right? Oops! That would make it abnormal. So maybe it’s abnormal, that is not a member of normal sets. Oops! That would make it normal. That just shows you that our natural intuitions about sets can lead us astray.

Fortunately there is an axiomatic set theory called the Zermelo–Fraenkel (or ZF) theory, which avoids such paradoxes. There are actually two versions of this theory: with or without the Axiom of Choice. The version without it seems to be too weak (not every vector space has a basis, the product of compact sets isn’t necessarily compact, etc.); the one with it (called ZFC) leads to weird non-intuitive consequences.

What bothers many mathematicians is that proofs that are based on set theory are rarely formal enough. It’s not that they can’t be made formal, it’s just that formalizing them would be so tedious that nobody wants to do it. Also, when you base any theory on set theory, you can formulate lots of idiotic theorems that have nothing to do with the theory in question but are only relevant to its clunky set-theoretical plumbing. It’s like the assembly language leaking out from higher abstractions. Sort of like programming in C.

Donuts are Tastier than Sets

Tired of all this nonsense with set theory, a group of Princeton guys and their guests decided to forget about sets and start from scratch. Their choice for the foundation of mathematics was the theory of homotopy. Homotopy is about paths — continuous maps from real numbers between 0 and 1 to topological spaces; and continuous deformations of such paths. The properties of paths capture the essential topological properties of spaces. For instance, if there is no path between a and b, it means that the space is not connected — it has at least two disjoint components — a sits in one and b in another.

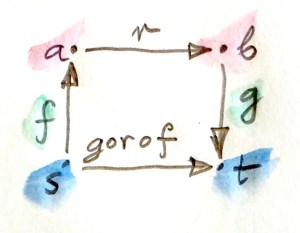

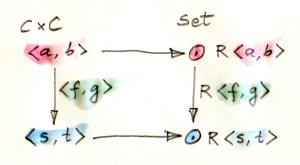

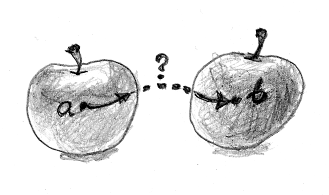

Two paths from a to b that cannot be continuously deformed into each other

If two paths between a and b cannot be deformed into each other, it means that there is a hole in space between them.

Obviously, this “traditional” formulation of homotopy relies heavily on set theory. A topological space, for instance, is defined in terms of open sets. So the first step is to distill the essence of homotopy theory by getting rid of sets. Enter Homotopy Type Theory. Paths and their deformations become primitives in the theory. We still get to use our intuitions about paths as curves inscribed on surfaces, but otherwise the math is totally abstract. There is a small set of axioms, the basic one asserting that the statement that a and b are equivalent is equivalent to the statement that they are equal. Of course the notions of equivalence and equality have special meanings and are very well defined in terms of primitives.

Cultural Digression

Why homotopy? I have my own theory about it. Our mathematics has roots in Ancient Greece, and the Greeks were not interested in developing technology because they had very cheap labor — slaves.

Euclid explaining geometry to his pupils in Raphael’s School of Athens

Instead, like all agricultural societies before them (Mesopotamia, Egypt), they were into owning land. Land owners are interested in geometry — Greek word γεωμετρία literally means measuring Earth. The “computers” of geometry were the slate, ruler and compass. Unlike technology, the science of measuring plots of land was generously subsidized by feudal societies. This is why the first rigorous mathematical theory was Euclid’s geometry, which happened to be based on axioms and logic. Euclid’s methodology culminated in the 20th century in Hilbert’s program of axiomatization of the whole of mathematics. This program crashed and burned when Gödel proved that any non-trivial theory (one containing arithmetic) is chock full of non-decidable theorems.

I was always wondering what mathematics would be like if it were invented by an industrial, rather than agricultural, society. The “computer” of an industrial society is the slide rule, which uses (the approximation of) real numbers and logarithms. What if Newton and Leibniz never studied Euclid? Would mathematics be based on calculus rather than geometry? Calculus is not easy to axiomatize, so we’d have to wait for the Euclid of calculus for a long time. The basic notions of calculus are Banach spaces, topology, and continuity. Topology and continuity happen to form the basis of homotopy theory as well. So if Greeks were an industrial society they could have treated homotopy as more basic than geometry. Geometry would then be discovered not by dividing plots of land but by studying solutions to analytic equations. Instead of defining a circle as a set of points equidistant from the center, as Euclid did, we would first define it as a solution to the equation x2+y2=r2.

Now imagine that this hypothetical industrial society also skipped the hunter-gather phase of development. That’s the period that gave birth to counting and natural numbers. I know it’s a stretch of imagination worthy a nerdy science fiction novel, but think of a society that would evolve from industrial robots if they were abandoned by humanity in a distant star system. Such a society could discover natural numbers by studying the topology of manifolds that are solutions to n-dimensional equations. The number of holes in a manifold is always a natural number. You can’t have half a hole!

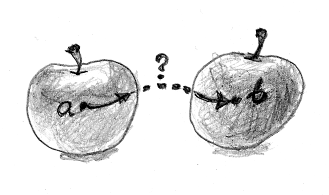

Instead of counting apples (or metal bolts) they would consider the homotopy of the two-apple space: Not all points in that space can be connected by continuous paths.

There is no continuous path between a and b

Maybe in the world where homotopy were the basis of all mathematics, Andrew Wiles’s proof of the Fermat’s Last Theorem could fit in a margin of a book — as long as it were a book on cohomology and elliptic curves (some of the areas of mathematics Wiles used in his proof). Prime numbers would probably be discovered by studying the zeros of the Riemann zeta function.

Industrial robot explaining to its pupils the homotopy of a two-apple space.

Quantum Digression

If our industrial robots were very tiny and explored the world at the quantum level (nanorobots?), they might try counting particles instead of apples. But in quantum mechanics, a two-particle state is not a direct product of two one-particle states. Two particles share the same wave function. In some cases this function can be factorized when particles are far apart, in others it can’t, giving rise to quantum entanglement. In quantum world, 2 is not always equal to 1+1.

In Quantum Field Theory (QFT — the relativistic counterpart of Quantum Mechanics), physicist calculate the so called S matrix that describes idealized experiments in which particles are far away from each other in the initial and final states. Since they don’t interact, they can be approximated by single-particle states. For instance, you can start with a proton and an antiproton coming at each other from opposite directions. They can be approximated as two separate particles. Then they smash into each other, produce a large multi-particle mess that escapes from the interaction region and is eventually seen as (approximately) separate particles by a big underground detector. (That’s, for instance, how the Higgs boson was discovered.) The number of particles in the final state may very well be different from the number of particles in the initial state. In general, QFT does not preserve the number of particles. There is no such conservation law.

Counting particles is very different from counting apples.

Relaxing Equality

In traditional mathematics, the notions of isomorphism and equality are very different. Isomorphism means (in Greek, literally) that things have the same shape, but aren’t necessarily equal. And yet mathematicians often treat isomorphic things as if they were equal. They prove a property of one thing and then assume that this property is also true for all things isomorphic. And it usually is, but nobody has the patience to prove it on the case-by-case basis. This phenomenon even has its own name: abuse of notation. It’s like writing programs in a language in which equality ‘==’ does not translate into the assembly-language CMP instruction followed be a conditional jump. We would like to work with structural identity, but all we do is compare pointers. You can overload operator ‘==’ in C++ but many a bug was the result of comparing pointers instead of values.

How can we make isomorphism more like equality? HoTT took quite an unusual approach by relaxing equality enough to make it plausibly equivalent to isomorphism.

HoTT’s homotopic version of equality is this: Two things are equal if there is a path between them. This equality is reflexive, symmetric, and transitive, just like equality is supposed to be. Reflexivity, for instance, tells us that x=x, and indeed there is always a trivial (constant) path from a point to itself. But there could also be other non-trivial paths looping from the point to itself. Some of them might not even be contractible. They all contribute to equality x=x.

There could be several paths between different points, a and b, making them “equal”: a=b. We are tempted to say that in this picture equality is a set of paths between points. Well, not exactly a set but the next best thing to a set — a type. So equality is a type, often called “identity type”, and two things are equal if the “identity type” for them is inhabited. That’s a very peculiar way to define equality. It’s an equality that carries with it a witness — a construction of an element of the equality type.

Relaxing Isomorphism

The first thing we could justifiably expect from any definition of equality is that if two things are equal they should be isomorphic. In other words, there should be an invertible function that maps one equal thing to another equal thing. This sound pretty obvious until you realize that, since equality is relaxed, it’s not! In fact we can’t prove strict isomorphism between things that are homotopically equal. But we do get a slightly relaxed version of isomorphism called equivalence. In HoTT, if things are equal they are equivalent. Phew, that’s a relief!

The trick is going the other way: Are equivalent things equal? In traditional mathematics that would be blatantly wrong — there are many isomorphic objects that are not equal. But with the HoTT’s notion of equality, there is nothing that would contradict it. In fact, the statement that equivalence is equivalent to equality can be added to HoTT as an axiom. It’s called Voevodski’s axiom of univalence.

It’s hard (or at least tedious), in traditional math, to prove that properties (propositions) can be carried over isomorphisms. With univalence, equivalence (generalized isomorphism) is the same as equality, and one can prove once and for all that propositions can be transported between equal objects. With univalence, the tedium of proving that if one object has a given property then all equivalent (“isomorphic”) object have the same property is eliminated.

Incidentally, where do types live? Is there (ahem!) a set of all types? There’s something better! A type of types called a Universe. Since a Universe is a type, is it a member of itself? You can almost see the Russel’s paradox looming in the background. But don’t despair, a Universe is not a member of itself, it’s a member of the higher Universe. In fact there are infinitely many Universes, each being a member of the next one.

Taking Roots

How does relaxed equality differ from the set-theoretical one? The simplest such example is the equality of Boolean types. There are two ways you can equal the Bool type to itself: One maps True to True and False to False, the other maps True to False and False to True. The first one is an identity mapping, but the second one is not — its square though is! (apply this mapping twice and you get back to original). Within HoTT you can take the square root of identity!

So here’s an interesting intuition for you: HoTT is to set theory as complex numbers are to real numbers (in complex numbers you can take a square root of -1). Paradoxically, complex numbers make a lot of things simpler. For instance, all quadratic equations are suddenly solvable. Sine and cosine become two projections of the same complex exponential. Riemann’s zeta function gains very interesting zeros on the imaginary line. The hope is that switching from sets to homotopy will lead to similar simplifications.

I like the example with flipping Booleans because it reminds me of an interesting quantum phenomenon. Imagine a quantum state with two identical particles. What happens when you switch the particles? If you get exactly the same state, the particles are called bosons (think photons). If you don’t, they are called fermions (think electrons). But when you flip fermions twice, you get back to the original state. In many ways fermions behave like square roots of bosons. For instance their equation of motion (Dirac equation) when squared produces the bosonic equation of motion (Klein-Gordon equation).

Computers Hate Sets

There is another way HoTT is better than set theory. (And, in my cultural analogy, that becomes more pertinent when an industrial society transitions to a computer society.) There is no good way to represent sets on a computer. Data structures that model sets are all fake. They always put some restrictions on the type of elements they can store. For instance the elements must be comparable, or hashable, or something. Even the simplest set of just two elements is implemented as an ordered pair — in sets you can’t have the first or the second element of a set (and in fact the definition of a pair as a set is quite tricky). You can easily write a program in Haskell that would take a (potenitally infinite) list of pairs and pick one element from each pair to form a (potentially infinite) list of picks. You can, for instance, tell the computer to pick the left element from each pair. Replace lists of pairs with sets of sets and you can’t do it! There is no constructive way of creating such a set and it’s very existence hinges on the axiom of choice.

This fact alone convinces me that set theory is not the best foundation for the theory of computing. But is homotopy a better assembly language for computing? We can’t represent sets using digital computers, but can we represent homotopy? Or should we start building computers from donuts and rubber strings? Maybe if we keep miniaturizing our computers down to the Planck scale, we could find a way to do calculations using loop quantum gravity, if it ever pans out.

Aharonov-Bohm Experiment

Even without invoking quantum gravity, quantum mechanics exhibits a lot of interesting non-local behaviors that often probe the topological properties of the surroundings. For instance, in the classic double-slit experiment, the fact that there are paths between the source of electrons and the screen that are not homotopically equivalent makes the electrons produce an interference pattern. But my favorite example is the Bohm-Aharonov experiment.

First, let me explain what a magnetic potential is. One of the Maxwell’s equations states that the divergence of the magnetic field is always zero (see a Tidbit at the end of this post that explains this notation):

This is the reason why magnetic field lines are always continuous. Interestingly, this equation has a solution that follows from the observation that the divergence of a curl is zero. So we can represent the magnetic field as a curl of some other vector field, which is called the magnetic potential A:

It’s just a clever mathematical trick. There is no way to measure magnetic potential, and the solution isn’t even unique: you can add a gradient of any scalar field to it and you’ll get the same magnetic field (the curl of a gradient is zero). So A is totally fake, it exists only as a device to simplify some calculations. Or is it…?

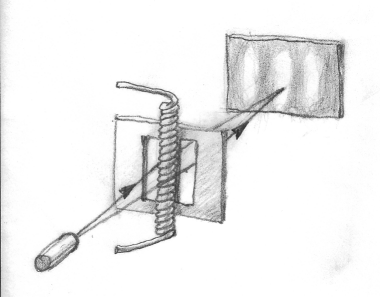

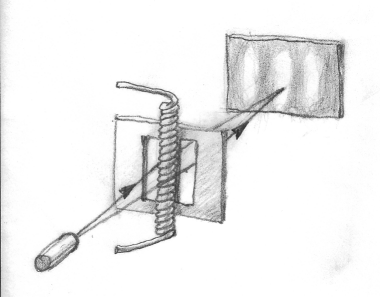

It turns out that electrons can sniff the magnetic potential, but only if there’s a hole in space. It turns out that, if you have a thin (almost) infinite linear coil with a current running through its windings, (almost) all magnetic field will be confined to its interior. Outside the coil there’s no magnetic field. However, there is a nonzero curl-free magnetic potential circling it. Now imagine using this coil as a separator between the two slits of the double-slit experiment. As before, there are two paths for the electron to follow: to the left of the coil and to the right of the coil. But now, along one path, the electron will be traveling with the lines of magnetic potential; along the other, against.

Aharononv-Bohm experiment. There are two paths available to the electron.

Magnetic potential doesn’t contribute to the electron’s energy or momentum but it does change its phase. So in the presence of the coil, the interference pattern in the two slit experiment shifts. That shift has been experimentally confirmed. The Aharonov-Bohm effect takes place because the electron is excluded from the part of space that is taken up by the coil — think of it as an infinite vertical line in space. The space available to the electron contains paths that cannot be continuously deformed into each other (they would have to cross the coil). In HoTT that would mean that although the point a, which is the source of the electron, and point b, where the electron hit the screen, are “equal,” there are two different members of the equality type.

The Incredible Quantum Homotopy Computer

The Aharonov-Bohm effect can be turned on and off by switching the current in the coil (actually, nobody uses coils in this experiment, but there is some promising research that uses nano-rings instead). If you can imagine a transistor built on the Aharonov-Bohm principle, you can easily imagine a computer. But can we go beyond digital computers and really explore varying homotopies?

I’ll be the first to admit that it might be too early to go to Kickstarter and solicit funds for a computer based on the Aharonov-Bohm effect that would be able to prove theorems formulated using Homotopy Type Theory; but the idea of breaking away from digital computing is worth a thought or two.

Or we can leave it to the post apocalyptic industrial-robot civilization that doesn’t even know what a digit is.

Acknowledgments

I’m grateful to the friendly (and patient) folks on the HoTT IRC channel for answering my questions and providing valuable insights.

Tidbit about Differential Operators

What are all those curls, divergences, and gradients? It’s just some vectors in 3-D space.

A scalar field φ(x, y, z) is a single function of space coordinates x, y, and z. You can calculate three different derivatives of this function with respect to x, y, and z. You can symbolically combine these three derivatives into one vector, (∂x, ∂y, ∂z). There is a symbol for that vector, called a nabla: ∇. If you apply a nabla to a scalar field, you get a vector field that is called the gradient, ∇φ, of that field. In coordinates, it is: (∂xφ, ∂yφ, ∂zφ).

A vector field V(x, y, z) is a triple of functions forming a vector at each point of space, (Vx, Vy, Vz). Magnetic field B and magnetic potential A are such vector fields. There are two ways you can apply a nabla to a vector field. One is just a scalar product of the nabla and the vector field, ∇·V, and it’s called the divergence of the vector field. In components, you can rewrite it as ∂xVx + ∂yVy + ∂zVz.

The other way of multiplying two vectors is called the vector product and its result is a vector. The vector product of the nabla and a vector field, ∇×A, is called the curl of that field. In components it is: (∂yAz – ∂zAy, ∂zAx – ∂xAz, ∂xAy – ∂yAx).

The vector product of two vectors is perpendicular to both. So when you then take a scalar product of the vector product with any of the original vectors, you get zero. This works also with nablas so, for instance, ∇·(∇×A) = 0 — the divergence of a curl is zero. That’s why the solution to ∇·B is B = ∇×A.

Similarly, because the vector product of a vector with itself is zero, we get ∇×∇φ = 0 — the curl of a gradient is zero. That’s why we can always add a term of the form ∇φ to A and get the same field B. In physics, this freedom is called gauge invariance.

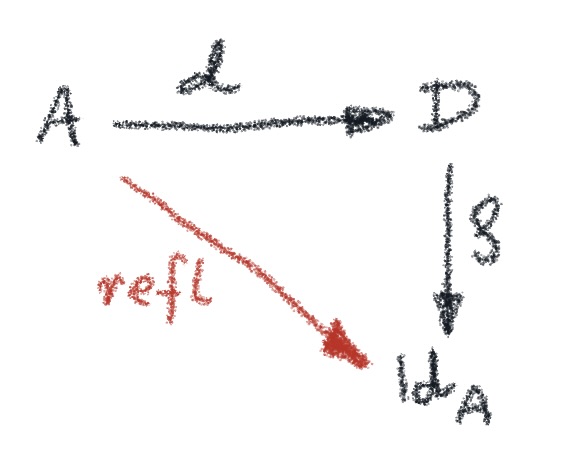

that makes the outer square commute, there are no additional constraints on

:

for

, and use the identity for

:

that makes the two triangles commute. But these commutation conditions tell us that

is the inverse of

and, consequently,

is isomorphic to

. It means that there are no paths in

other than those given by reflexivity.

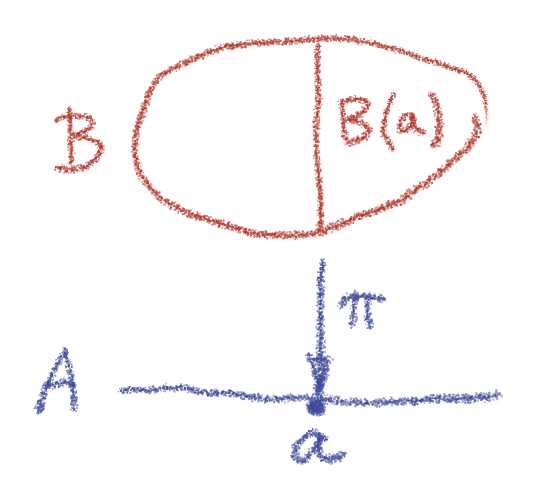

to be a fibration. Thus we need a more restrictive model in which not all mappings are fibrations.

as a cofibration. We want different values

to be mapped to different “paths”

, and we’d also like to have some non-trivial paths left over to play with.

: it’s a continuous mapping from a unit interval,

. In a cartesian category with weak equivalences, we can use an abstract definition of the object representing the space of all paths in

. A path space object

is an object that factorizes the diagonal morphism

, such that

is a weak equivalence.

be a fibration, defining a good path object; and

be a cofibration (therefore a trivial cofibration) defining a very good path object.

produces the start and the end of a path, and

sends a point to a constant path.

to be a trivial cofibration, that is a cofibration that’s a weak homotopy equivalence. Weak equivalence let us shrink all paths. Imagine a path as a rubber band. We fix one end and of the path and let the other end slide all the way back until the path becomes constant. (In the compact/open topology of

, this works also for closed loops.)

over the diagonal of

, can be uniquely extended to all paths?

, you might not have much choice as to which value of type

to pick next. In fact, there might be only one value available to you — the “closest one” in the direction you’re going. To choose any other value, you’d have to “jump,” which would break continuity.

by growing it from its initial value

. You gradually extend it above the path

until you reach the point directly above

. (In fact, this is the rough idea behind cubical type theory.)

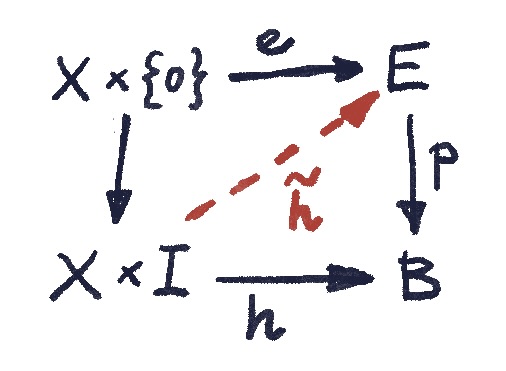

to

in

has a unique lifting

in

that starts at

.

:

is not a fibration.

is a cofibration,

is a fibration, and one of them is a weak equivalence:

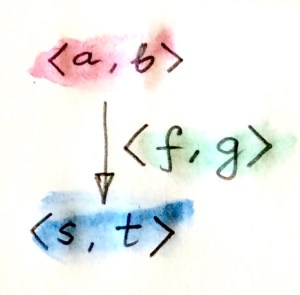

. Such iterated types correspond to higher homotopies: paths between paths, and so on, ad infinitum. The structure that arises is called a weak infinity groupoid. It’s a category in which every morphism has an inverse (just follow the same path backwards), and category laws (identity or associativity) are satisifed up to higher morphisms (higher homotopies).