I always believed that the main problems in designing a programming language were resource management and concurrency–and the two are related. If you can track ownership of resources, you can be sure that no synchronization is needed when there’s a single owner.

I’ve been evangelizing resource management for a long time, first in C++, and then in D (see Appendix 3). I was happy to see it implemented in Rust as ownership types, and I’m happy to see it coming to Haskell as linear types.

Haskell has essentially solved the concurrency and parallelism problems by channeling mutation to dedicated monads, but resource management has always been part of the awkward squad. The main advantage of linear types in Haskell, other than dealing with external resources, is to allow safe mutation and non-GC memory management. This could potentially lead to substantial performance gains.

This post is based on very informative discussions I had with Arnaud Spiwack, who explained to me the work he’d done on linear types and linear lenses, some of it never before documented.

The PDF version of this post together with complete Haskell code is available on GitHub.

Linear types

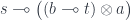

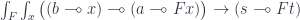

What is a linear function? The short answer is that a linear function  “consumes” its argument exactly once. This is not the whole truth, though, because we also have linear identity

“consumes” its argument exactly once. This is not the whole truth, though, because we also have linear identity  , which ostensibly does not consume

, which ostensibly does not consume  . The long answer is that a linear function consumes its argument exactly once if it itself is consumed exactly once, and its result is consumed exactly once.

. The long answer is that a linear function consumes its argument exactly once if it itself is consumed exactly once, and its result is consumed exactly once.

What remains to define is what it means to be consumed. A function is consumed when it’s applied to its argument. A base value like Int or Char is consumed when it’s evaluated, and an algebraic data type is consumed when it’s pattern-matched and all its matched components are consumed.

For instance, to consume a linear pair (a, b), you pattern-match it and then consume both a and b. To consume Either a b, you pattern-match it and consume the matched component, either a or b, depending on which branch was taken.

As you can see, except for the base values, a linear argument is like a hot potato: you “consume” it by passing it to somebody else.

So where does the buck stop? This is where the magic happens: Every resource comes with a special primitive that gets rid of it. A file handle gets closed, memory gets deallocated, an array gets frozen, and Frodo throws the ring into the fires of Mount Doom.

To notify the type system that the resource has been destroyed, a linear function will return a value inside the special unrestricted type Ur. When this type is pattern-matched, the original resource is finally destroyed.

For instance, for linear arrays, one such primitive is toList:

![\mathit{toList} \colon \text{Array} \; a \multimap \text{Ur} \, [a]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cmathit%7BtoList%7D+%5Ccolon+%5Ctext%7BArray%7D+%5C%3B+a+%5Cmultimap+%5Ctext%7BUr%7D+%5C%2C+%5Ba%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=29303b&s=0&c=20201002)

In Haskell, we annotate the linear arrows with multiplicity 1:

toList :: Array a %1-> Ur [a]

Similarly, magic is used to create the resource in the first place. For arrays, this happens inside the primitive fromList.

![\mathit{fromList} \colon [a] \to (\text{Array} \; a \multimap \text{Ur} \; b) \multimap \text{Ur} \; b](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cmathit%7BfromList%7D+%5Ccolon+%5Ba%5D+%5Cto+%28%5Ctext%7BArray%7D+%5C%3B+a+%5Cmultimap+%5Ctext%7BUr%7D+%5C%3B+b%29+%5Cmultimap+%5Ctext%7BUr%7D+%5C%3B+b+&bg=ffffff&fg=29303b&s=0&c=20201002)

or using Haskell syntax:

fromList :: [a] -> (Array a %1-> Ur b) %1-> Ur b

The kind of resource management I advertised in C++ was scope based. A resource was encapsulated in a smart pointer that was automatically destroyed at scope exit.

With linear types, the role of the scope is played by a user-provided linear function; here, the continuation:

(Array a %1 -> Ur b)

The primitive fromList promises to consume this user-provided function exactly once and to return its unrestricted result. The client is obliged to consume the array exactly once (e.g., by calling toList). This obligation is encoded in the type of the continuation accepted by fromList.

Linear lens: The existential form

A lens abstracts the idea of focusing on a part of a larger data structure. It is used to access or modify its focus. An existential form of a lens consists of two functions: one splitting the source into the focus and the residue; and the other replacing the focus with a new value, and creating a new whole. We don’t care about the actual type of the residue so we keep it as an existential.

The way to think about a linear lens is to consider its source as a resource. The act of splitting it into a focus and a residue is destructive: it consumes its source to produce two new resources. It splits one hot potato s into two hot potatoes: the residue c and the focus a.

Conversely, the part that rebuilds the target t must consume both the residue c and the new focus b.

We end up with the following Haskell implementation:

data LinLensEx a b s t where

LinLensEx :: (s %1-> (c, a)) ->

((c, b) %1-> t) -> LinLensEx a b s t

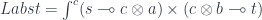

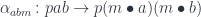

A Haskell existential type corresponds to a categorical coend, so the above definition is equivalent to:

I use the lollipop notation for the hom-set in a monoidal category with a tensor product  .

.

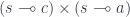

The important property of a monoidal category is that its tensor product doesn’t come with a pair of projections; and the unit object is not terminal. In particular, a morphism  cannot be decomposed into a product of two morphisms

cannot be decomposed into a product of two morphisms  .

.

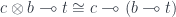

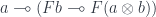

However, in a closed monoidal category we can curry a mapping out of a tensor product:

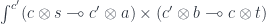

We can therefore rewrite the existential lens as:

and then apply the co-Yoneda lemma to get:

Unlike the case of a standard lens, this form cannot be separated into a get/set pair.

The intuition is that a linear lens lets you consume the object  , but it leaves you with the obligation to consume both the setter

, but it leaves you with the obligation to consume both the setter  and the focus

and the focus  . You can’t just extract

. You can’t just extract  alone, because that would leave a gaping hole in your object. You have to plug it in with a new object

alone, because that would leave a gaping hole in your object. You have to plug it in with a new object  , and that’s what the setter lets you do.

, and that’s what the setter lets you do.

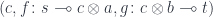

Here’s the Haskell translation of this formula (conventionally, with the pairs of arguments reversed):

type LinLens s t a b = s %1-> (b %1-> t, a)

The Yoneda shenanigans translate into a pair of Haskell functions. Notice that, just like in the co-Yoneda trick, the existential  is replaced by the linear function

is replaced by the linear function  .

.

fromLinLens :: forall s t a b.

LinLens s t a b -> LinLensEx a b s t

fromLinLens h = LinLensEx f g

where

f :: s %1-> (b %1-> t, a)

f = h

g :: (b %1-> t, b) %1-> t

g (set, b) = set b

The inverse mapping is:

toLinLens :: LinLensEx a b s t -> LinLens s t a b

toLinLens (LinLensEx f g) s =

case f s of

(c, a) -> (\b -> g (c, b), a)

Profunctor representation

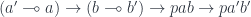

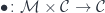

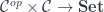

Every optic comes with a profunctor representation and the linear lens is no exception. Categorically speaking, a profunctor is a functor from the product category  to

to  . It maps pairs of object to sets, and pairs of morphisms to functions. Since we are in a monoidal category, the morphisms are linear functions, but the mappings between sets are regular functions (see Appendix 1). Thus the action of the profunctor

. It maps pairs of object to sets, and pairs of morphisms to functions. Since we are in a monoidal category, the morphisms are linear functions, but the mappings between sets are regular functions (see Appendix 1). Thus the action of the profunctor  on morphisms is a function:

on morphisms is a function:

In Haskell:

class Profunctor p where

dimap :: (a' %1-> a) -> (b %1-> b') -> p a b -> p a' b'

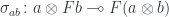

A Tambara module (a.k.a., a strong profunctor) is a profunctor equipped with the following mapping:

natural in  and

and  , dintural in

, dintural in  .

.

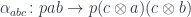

In Haskell, this translates to a polymorphic function:

class (Profunctor p) => Tambara p where

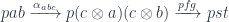

alpha :: forall a b c. p a b -> p (c, a) (c, b)

The linear lens  is itself a Tambara module, for fixed

is itself a Tambara module, for fixed  . To show this, let’s construct a mapping:

. To show this, let’s construct a mapping:

Expanding the definition:

By cocontinuity of the hom-set in  , a mapping out of a coend is equivalent to an end:

, a mapping out of a coend is equivalent to an end:

Given a pair of linear arrows on the left we want to construct a coend on the right. We can do it by first lifting both arrow by  . We get:

. We get:

We can inject them into the coend on the right at  .

.

In Haskell, we construct the instance of the Profunctor class for the linear lens:

instance Profunctor (LinLensEx a b) where

dimap f' g' (LinLensEx f g) = LinLensEx (f . f') (g' . g)

and the instance of Tambara:

instance Tambara (LinLensEx a b) where

alpha (LinLensEx f g) =

LinLensEx (unassoc . second f) (second g . assoc)

Linear lenses can be composed and there is an identity linear lens:

given by injecting the pair  at

at  , the monoidal unit.

, the monoidal unit.

In Haskell, we can construct the identity lens using the left unitor (see Appendix 1):

idLens :: LinLensEx a b a b

idLens = LinLensEx unlunit lunit

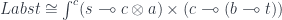

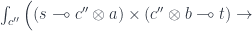

The profunctor representation of a linear lens is given by an end over Tambara modules:

In Haskell, this translates to a type of functions polymorphic in Tambara modules:

type PLens a b s t = forall p. Tambara p => p a b -> p s t

The advantage of this representation is that it lets us compose linear lenses using simple function composition.

Here’s the categorical proof of the equivalence. Left to right: Given a triple:  , we construct:

, we construct:

Conversely, given a polymorphic (in Tambara modules) function  , we can apply it to the identity optic

, we can apply it to the identity optic  and obtain

and obtain  .

.

In Haskell, this equivalence is witnessed by the following pair of functions:

fromPLens :: PLens a b s t -> LinLensEx a b s t

fromPLens f = f idLens

toPLens :: LinLensEx a b s t -> PLens a b s t

toPLens (LinLensEx f g) pab = dimap f g (alpha pab)

van Laarhoven representation

Similar to regular lenses, linear lenses have a functor-polymorphic van Laarhoven encoding. The difference is that we have to use endofunctors in the monoidal subcategory, where all arrows are linear:

class Functor f where

fmap :: (a %1-> b) %1-> f a %1-> f b

Just like regular Haskell functors, linear functors are strong. We define strength as:

strength :: Functor f => (a, f b) %1-> f (a, b)

strength (a, fb) = fmap (eta a) fb

where eta is the unit of the currying adjunction (see Appendix 1).

With this definition, the van Laarhoven encoding of linear lenses is:

type VLL s t a b = forall f. Functor f =>

(a %1-> f b) -> (s %1-> f t)

The equivalence of the two encodings is witnessed by a pair of functions:

toVLL :: LinLens s t a b -> VLL s t a b

toVLL lns f = fmap apply . strength . second f . lns

fromVLL :: forall s t a b. VLL s t a b -> LinLens s t a b

fromVLL vll s = unF (vll (F id) s)

Here, the functor F is defined as a linear pair (a tensor product):

data F a b x where

F :: (b %1-> x) %1-> a %1-> F a b x

unF :: F a b x %1-> (b %1-> x, a)

unF (F bx a) = (bx, a)

with the obvious implementation of fmap

instance Functor (F a b) where

fmap f (F bx a) = F (f . bx) a

You can find the categorical derivation of van Laarhoven representation in Appendix 2.

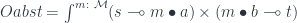

Linear optics

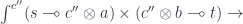

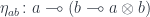

Linear lenses are but one example of more general linear optics. Linear optics are defined by the action of a monoidal category  on (possibly the same) monoidal category

on (possibly the same) monoidal category  :

:

In particular, one can define linear prisms and linear traversals using actions by a coproduct or a power series.

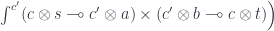

The existential form is given by:

There is a corresponding Tambara representation, with the following Tambara structure:

Incidentally, the two hom-sets in the definition of the optic can come from two different categories, so it’s possible to mix linear and non-linear arrows in one optic.

Appendix: 1 Closed monoidal category in Haskell

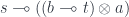

With the advent of linear types we now have two main categories lurking inside Haskell. They have the same objects–Haskell types– but the monoidal category has fewer arrows. These are the linear arrows  . They can be composed:

. They can be composed:

(.) :: (b %1-> c) %1-> (a %1-> b) %1-> a %1 -> c

(f . g) x = f (g x)

and there is an identity arrow for every object:

id :: a %1-> a

id a = a

In general, a tensor product in a monoidal category is a bifunctor:  . In Haskell, we identify the tensor product

. In Haskell, we identify the tensor product  with the built-in product

with the built-in product (a, b). The difference is that, within the monoidal category, this product doesn’t have projections. There is no linear arrow  or

or  . Consequently, there is no diagonal map

. Consequently, there is no diagonal map  , and the unit object

, and the unit object  is not terminal: there is no arrow

is not terminal: there is no arrow  .

.

We define the action of a bifunctor on a pair of linear arrows entirely within the monoidal category:

class Bifunctor p where

bimap :: (a %1-> a') %1-> (b %1-> b') %1->

p a b %1-> p a' b'

first :: (a %1-> a') %1-> p a b %1-> p a' b

first f = bimap f id

second :: (b %1-> b') %1-> p a b %1-> p a b'

second = bimap id

The product is itself an instance of this linear bifunctor:

instance Bifunctor (,) where

bimap f g (a, b) = (f a, g b)

The tensor product has to satisfy coherence conditions–associativity and unit laws:

assoc :: ((a, b), c) %1-> (a, (b, c))

assoc ((a, b), c) = (a, (b, c))

unassoc :: (a, (b, c)) %1-> ((a, b), c)

unassoc (a, (b, c)) = ((a, b), c)

lunit :: ((), a) %1-> a

lunit ((), a) = a

unlunit :: a %1-> ((), a)

unlunit a = ((), a)

In Haskell, the type of arrows between any two objects is also an object. A category in which this is true is called closed. This identification is the consequence of the currying adjunction between the product and the function type. In a closed monoidal category, there is a corresponding adjunction between the tensor product and the object of linear arrows. The mapping out of a tensor product is equivalent to the mapping into the function object. In Haskell, this is witnessed by a pair of mappings:

curry :: ((a, b) %1-> c) %1-> (a %1-> (b %1-> c))

curry f x y = f (x, y)

uncurry :: (a %1-> (b %1-> c)) %1-> ((a, b) %1-> c)

uncurry f (x, y) = f x y

Every adjunction also defines a pair of unit and counit natural transformations:

eta :: a %1-> b %1-> (a, b)

eta a b = (a, b)

apply :: (a %1-> b, a) %-> b

apply (f, a) = f a

We can, for instance, use the unit to implement a point-free mapping of lenses:

toLinLens :: LinLensEx a b s t -> LinLens s t a b

toLinLens (LinLensEx f g) = first ((g .) . eta) . f

Finally, a note about the Haskell definition of a profunctor:

class Profunctor p where

dimap :: (a' %1-> a) -> (b %1-> b') -> p a b -> p a' b'

Notice the mixing of two types of arrows. This is because a profunctor is defined as a mapping  . Here,

. Here,  is the monoidal category, so the arrows in it are linear. But

is the monoidal category, so the arrows in it are linear. But p a b is just a set, and the mapping p a b -> p a' b' is just a regular function. Similarly, the type:

(a' %1-> a)

is not treated as an object in  but rather as a set of linear arrows. In fact this hom-set is itself a profunctor:

but rather as a set of linear arrows. In fact this hom-set is itself a profunctor:

newtype Hom a b = Hom (a %1-> b)

instance Profunctor Hom where

dimap f g (Hom h) = Hom (g . h . f)

As you might have noticed, there are many definitions that extend the usual Haskel concepts to linear types. Since it makes no sense to re-introduce, and give new names to each of them, the linear extensions are written using multiplicity polymorphism. For instance, the most general currying function is written as:

curry :: ((a, b) %p -> c) %q -> a %p -> b %p -> c

covering four different combinations of multiplicities.

Appendix 2: van Laarhoven representation

We start by defining functorial strength in a monoidal category:

To begin with, we can curry  . Thus we have to construct:

. Thus we have to construct:

We have at our disposal the counit of the currying adjunction:

We can apply  to

to  and lift the resulting map

and lift the resulting map  to arrive at

to arrive at  .

.

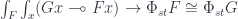

Now let’s write the van Laarhoven representation as the end of the mapping of two linear hom-sets:

![\int_{F \colon [\mathcal C, \mathcal C]} (a \multimap F b) \to (s \multimap F t)](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cint_%7BF+%5Ccolon+%5B%5Cmathcal+C%2C+%5Cmathcal+C%5D%7D+%28a+%5Cmultimap+F+b%29+%5Cto+%28s+%5Cmultimap+F+t%29+&bg=ffffff&fg=29303b&s=0&c=20201002)

We use the Yoneda lemma to replace  with a set of natural transformations, written as an end over

with a set of natural transformations, written as an end over  :

:

We can uncurry it:

and apply the ninja-Yoneda lemma in the functor category to get:

Here, the ninja-Yoneda lemma operates on higher-order functors, such as  . It can be written as:

. It can be written as:

Appendix 3: My resource management curriculum

These are some of my blog posts and articles about resource management and its application to concurrent programming.

- Strong Pointers and Resource Management in C++,

- Walking Down Memory Lane, 2005 (with Andrei Alexandrescu)

- unique ptr–How Unique is it?, 2009

- Unique Objects, 2009

- Race-free Multithreading, 2009

- Part 1: Ownership

- Part 2: Owner Polymorphism

- Edward C++ hands, 2013

between two virtual objects corresponding to two presheaves

and

. Indeed, for every

, seen as an arrow

, we get an arrow

simply by composition

. Notice that we are thus defining the composition with

, because we are outside of the original category. A component

of a natural transformation is a mapping between two arrows.

, consider a zigzag path from

to

given by

. The two ways of associating this composition give us

.

is a bunch of arrows converging on

satisfying certain conditions. These conditions are defined in terms of a coverage. For every object

we define a whole family of covers, and then combine them into one big collection that we call the coverage.

, if we pick a compatible family of

that agrees on all overlaps, then this uniquely determines the element (virtual arrow)

.

is a presheaf that extends a cover

. It assigns a singleton set to each

and all its open subsets (that is objects that have arrows pointing to

); and an empty set otherwise. In particular, the sieve includes all the overlaps, like

, even if they are not present in the original cover.

. Indeed,

maps all objects either to singletons or to empty sets. In terms of virtual arrows, there is at most one arrow going to

from any object. This is why a natural transformation from

to any presheaf

produces a family of arrows

. It picks a single arrow from each of the hom-sets

.

. Thus a family generated by a natural transformation

is automatically a compatible family. Therefore, if

is a sheaf, it determines a unique element

.

is a sheaf if and only if, for every covering sieve

of every

, there is a one-to-one correspondence between the set of natural transformations

and the set

.

and

.