This is part 8 of Categories for Programmers. Previously: Functors. See the Table of Contents.

Now that you know what a functor is, and have seen a few examples, let’s see how we can build larger functors from smaller ones. In particular it’s interesting to see which type constructors (which correspond to mappings between objects in a category) can be extended to functors (which include mappings between morphisms).

Bifunctors

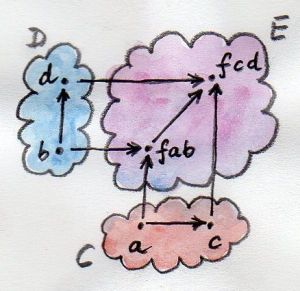

Since functors are morphisms in Cat (the category of categories), a lot of intuitions about morphisms — and functions in particular — apply to functors as well. For instance, just like you can have a function of two arguments, you can have a functor of two arguments, or a bifunctor. On objects, a bifunctor maps every pair of objects, one from category C, and one from category D, to an object in category E. Notice that this is just saying that it’s a mapping from a cartesian product of categories C×D to E.

That’s pretty straightforward. But functoriality means that a bifunctor has to map morphisms as well. This time, though, it must map a pair of morphisms, one from C and one from D, to a morphism in E.

Again, a pair of morphisms is just a single morphism in the product category C×D. We define a morphism in a cartesian product of categories as a pair of morphisms which goes from one pair of objects to another pair of objects. These pairs of morphisms can be composed in the obvious way:

(f, g) ∘ (f', g') = (f ∘ f', g ∘ g')

The composition is associative and it has an identity — a pair of identity morphisms (id, id). So a cartesian product of categories is indeed a category.

An easier way to think about bifunctors would be to consider them functors in each argument separately. So instead of translating functorial laws — associativity and identity preservation — from functors to bifunctors, it would be enough to check them separately for each argument. However, in general, separate functoriality is not enough to prove joint functoriality. Categories in which joint functoriality fails are called premonoidal.

Let’s define a bifunctor in Haskell. In this case all three categories are the same: the category of Haskell types. A bifunctor is a type constructor that takes two type arguments. Here’s the definition of the Bifunctor typeclass taken directly from the library Control.Bifunctor:

class Bifunctor f where bimap :: (a -> c) -> (b -> d) -> f a b -> f c d bimap g h = first g . second h first :: (a -> c) -> f a b -> f c b first g = bimap g id second :: (b -> d) -> f a b -> f a d second = bimap id

The type variable f represents the bifunctor. You can see that in all type signatures it’s always applied to two type arguments. The first type signature defines bimap: a mapping of two functions at once. The result is a lifted function, (f a b -> f c d), operating on types generated by the bifunctor’s type constructor. There is a default implementation of bimap in terms of first and second, which shows that it’s enough to have functoriality in each argument separately to be able to define a bifunctor. (As mentioned before, this doesn’t always work, because the two maps may not commute, that is first g . second h may not be the same as second h . first g.)

The two other type signatures, first and second, are the two fmaps witnessing the functoriality of f in the first and the second argument, respectively.

The typeclass definition provides default implementations for both of them in terms of bimap.

When declaring an instance of Bifunctor, you have a choice of either implementing bimap and accepting the defaults for first and second, or implementing both first and second and accepting the default for bimap (of course, you may implement all three of them, but then it’s up to you to make sure they are related to each other in this manner).

Product and Coproduct Bifunctors

An important example of a bifunctor is the categorical product — a product of two objects that is defined by a universal construction. If the product exists for any pair of objects, the mapping from those objects to the product is bifunctorial. This is true in general, and in Haskell in particular. Here’s the Bifunctor instance for a pair constructor — the simplest product type:

instance Bifunctor (,) where

bimap f g (x, y) = (f x, g y)

There isn’t much choice: bimap simply applies the first function to the first component, and the second function to the second component of a pair. The code pretty much writes itself, given the types:

bimap :: (a -> c) -> (b -> d) -> (a, b) -> (c, d)

The action of the bifunctor here is to make pairs of types, for instance:

(,) a b = (a, b)

By duality, a coproduct, if it’s defined for every pair of objects in a category, is also a bifunctor. In Haskell, this is exemplified by the Either type constructor being an instance of Bifunctor:

instance Bifunctor Either where

bimap f _ (Left x) = Left (f x)

bimap _ g (Right y) = Right (g y)

This code also writes itself.

Now, remember when we talked about monoidal categories? A monoidal category defines a binary operator acting on objects, together with a unit object. I mentioned that Set is a monoidal category with respect to cartesian product, with the singleton set as a unit. And it’s also a monoidal category with respect to disjoint union, with the empty set as a unit. What I haven’t mentioned is that one of the requirements for a monoidal category is that the binary operator be a bifunctor. This is a very important requirement — we want the monoidal product to be compatible with the structure of the category, which is defined by morphisms. We are now one step closer to the full definition of a monoidal category (we still need to learn about naturality, before we can get there).

Functorial Algebraic Data Types

We’ve seen several examples of parameterized data types that turned out to be functors — we were able to define fmap for them. Complex data types are constructed from simpler data types. In particular, algebraic data types (ADTs) are created using sums and products. We have just seen that sums and products are functorial. We also know that functors compose. So if we can show that the basic building blocks of ADTs are functorial, we’ll know that parameterized ADTs are functorial too.

So what are the building blocks of parameterized algebraic data types? First, there are the items that have no dependency on the type parameter of the functor, like Nothing in Maybe, or Nil in List. They are equivalent to the Const functor. Remember, the Const functor ignores its type parameter (really, the second type parameter, which is the one of interest to us, the first one being kept constant).

Then there are the elements that simply encapsulate the type parameter itself, like Just in Maybe. They are equivalent to the identity functor. I mentioned the identity functor previously, as the identity morphism in Cat, but didn’t give its definition in Haskell. Here it is:

data Identity a = Identity a

instance Functor Identity where

fmap f (Identity x) = Identity (f x)

You can think of Identity as the simplest possible container that always stores just one (immutable) value of type a.

Everything else in algebraic data structures is constructed from these two primitives using products and sums.

With this new knowledge, let’s have a fresh look at the Maybe type constructor:

data Maybe a = Nothing | Just a

It’s a sum of two types, and we now know that the sum is functorial. The first part, Nothing can be represented as a Const () acting on a (the first type parameter of Const is set to unit — later we’ll see more interesting uses of Const). The second part is just a different name for the identity functor. We could have defined Maybe, up to isomorphism, as:

type Maybe a = Either (Const () a) (Identity a)

So Maybe is the composition of the bifunctor Either with two functors, Const () and Identity. (Const is really a bifunctor, but here we always use it partially applied.)

We’ve already seen that a composition of functors is a functor — we can easily convince ourselves that the same is true of bifunctors. All we need is to figure out how a composition of a bifunctor with two functors works on morphisms. Given two morphisms, we simply lift one with one functor and the other with the other functor. We then lift the resulting pair of lifted morphisms with the bifunctor.

We can express this composition in Haskell. Let’s define a data type that is parameterized by a bifunctor bf (it’s a type variable that is a type constructor that takes two types as arguments), two functors fu and gu (type constructors that take one type variable each), and two regular types a and b. We apply fu to a and gu to b, and then apply bf to the resulting two types:

newtype BiComp bf fu gu a b = BiComp (bf (fu a) (gu b))

That’s the composition on objects, or types. Notice how in Haskell we apply type constructors to types, just like we apply functions to arguments. The syntax is the same.

If you’re getting a little lost, try applying BiComp to Either, Const (), Identity, a, and b, in this order. You will recover our bare-bone version of Maybe b (a is ignored).

The new data type BiComp is a bifunctor in a and b, but only if bf is itself a Bifunctor and fu and gu are Functors. The compiler must know that there will be a definition of bimap available for bf, and definitions of fmap for fu and gu. In Haskell, this is expressed as a precondition in the instance declaration: a set of class constraints followed by a double arrow:

instance (Bifunctor bf, Functor fu, Functor gu) => Bifunctor (BiComp bf fu gu) where bimap f1 f2 (BiComp x) = BiComp ((bimap (fmap f1) (fmap f2)) x)

The implementation of bimap for BiComp is given in terms of bimap for bf and the two fmaps for fu and gu. The compiler automatically infers all the types and picks the correct overloaded functions whenever BiComp is used.

The x in the definition of bimap has the type:

bf (fu a) (gu b)

which is quite a mouthful. The outer bimap breaks through the outer bf layer, and the two fmaps dig under fu and gu, respectively. If the types of f1 and f2 are:

f1 :: a -> a' f2 :: b -> b'

then the final result is of the type bf (fu a') (gu b'):

bimapbf :: (fu a -> fu a') -> (gu b -> gu b') -> bf (fu a) (gu b) -> bf (fu a') (gu b')

If you like jigsaw puzzles, these kinds of type manipulations can provide hours of entertainment.

So it turns out that we didn’t have to prove that Maybe was a functor — this fact followed from the way it was constructed as a sum of two functorial primitives.

A perceptive reader might ask the question: If the derivation of the Functor instance for algebraic data types is so mechanical, can’t it be automated and performed by the compiler? Indeed, it can, and it is. You need to enable a particular Haskell extension by including this line at the top of your source file:

{-# LANGUAGE DeriveFunctor #-}

and then add deriving Functor to your data structure:

data Maybe a = Nothing | Just a deriving Functor

and the corresponding fmap will be implemented for you.

The regularity of algebraic data structures makes it possible to derive instances not only of Functor but of several other type classes, including the Eq type class I mentioned before. There is also the option of teaching the compiler to derive instances of your own typeclasses, but that’s a bit more advanced. The idea though is the same: You provide the behavior for the basic building blocks and sums and products, and let the compiler figure out the rest.

Functors in C++

If you are a C++ programmer, you obviously are on your own as far as implementing functors goes. However, you should be able to recognize some types of algebraic data structures in C++. If such a data structure is made into a generic template, you should be able to quickly implement fmap for it.

Let’s have a look at a tree data structure, which we would define in Haskell as a recursive sum type:

data Tree a = Leaf a | Node (Tree a) (Tree a)

deriving Functor

As I mentioned before, one way of implementing sum types in C++ is through class hierarchies. It would be natural, in an object-oriented language, to implement fmap as a virtual function of the base class Functor and then override it in all subclasses. Unfortunately this is impossible because fmap is a template, parameterized not only by the type of the object it’s acting upon (the this pointer) but also by the return type of the function that’s been applied to it. Virtual functions cannot be templatized in C++. We’ll implement fmap as a generic free function, and we’ll replace pattern matching with dynamic_cast.

The base class must define at least one virtual function in order to support dynamic casting, so we’ll make the destructor virtual (which is a good idea in any case):

template<class T>

struct Tree {

virtual ~Tree() {};

};

The Leaf is just an Identity functor in disguise:

template<class T>

struct Leaf : public Tree<T> {

T _label;

Leaf(T l) : _label(l) {}

};

The Node is a product type:

template<class T>

struct Node : public Tree<T> {

Tree<T> * _left;

Tree<T> * _right;

Node(Tree<T> * l, Tree<T> * r) : _left(l), _right(r) {}

};

When implementing fmap we take advantage of dynamic dispatching on the type of the Tree. The Leaf case applies the Identity version of fmap, and the Node case is treated like a bifunctor composed with two copies of the Tree functor. As a C++ programmer, you’re probably not used to analyzing code in these terms, but it’s a good exercise in categorical thinking.

template<class A, class B>

Tree<B> * fmap(std::function<B(A)> f, Tree<A> * t)

{

Leaf<A> * pl = dynamic_cast <Leaf<A>*>(t);

if (pl)

return new Leaf<B>(f (pl->_label));

Node<A> * pn = dynamic_cast<Node<A>*>(t);

if (pn)

return new Node<B>( fmap<A>(f, pn->_left)

, fmap<A>(f, pn->_right));

return nullptr;

}

For simplicity, I decided to ignore memory and resource management issues, but in production code you would probably use smart pointers (unique or shared, depending on your policy).

Compare it with the Haskell implementation of fmap:

instance Functor Tree where

fmap f (Leaf a) = Leaf (f a)

fmap f (Node t t') = Node (fmap f t) (fmap f t')

This implementation can also be automatically derived by the compiler.

The Writer Functor

I promised that I would come back to the Kleisli category I described earlier. Morphisms in that category were represented as “embellished” functions returning the Writer data structure.

type Writer a = (a, String)

I said that the embellishment was somehow related to endofunctors. And, indeed, the Writer type constructor is functorial in a. We don’t even have to implement fmap for it, because it’s just a simple product type.

But what’s the relation between a Kleisli category and a functor — in general? A Kleisli category, being a category, defines composition and identity. Let’ me remind you that the composition is given by the fish operator:

(>=>) :: (a -> Writer b) -> (b -> Writer c) -> (a -> Writer c)

m1 >=> m2 = \x ->

let (y, s1) = m1 x

(z, s2) = m2 y

in (z, s1 ++ s2)

and the identity morphism by a function called return:

return :: a -> Writer a return x = (x, "")

It turns out that, if you look at the types of these two functions long enough (and I mean, long enough), you can find a way to combine them to produce a function with the right type signature to serve as fmap. Like this:

fmap f = id >=> (\x -> return (f x))

Here, the fish operator combines two functions: one of them is the familiar id, and the other is a lambda that applies return to the result of acting with f on the lambda’s argument. The hardest part to wrap your brain around is probably the use of id. Isn’t the argument to the fish operator supposed to be a function that takes a “normal” type and returns an embellished type? Well, not really. Nobody says that a in a -> Writer b must be a “normal” type. It’s a type variable, so it can be anything, in particular it can be an embellished type, like Writer b.

So id will take Writer a and turn it into Writer a. The fish operator will fish out the value of a and pass it as x to the lambda. There, f will turn it into a b and return will embellish it, making it Writer b. Putting it all together, we end up with a function that takes Writer a and returns Writer b, exactly what fmap is supposed to produce.

Notice that this argument is very general: you can replace Writer with any type constructor. As long as it supports a fish operator and return, you can define fmap as well. So the embellishment in the Kleisli category is always a functor. (Not every functor, though, gives rise to a Kleisli category.)

You might wonder if the fmap we have just defined is the same fmap the compiler would have derived for us with deriving Functor. Interestingly enough, it is. This is due to the way Haskell implements polymorphic functions. It’s called parametric polymorphism, and it’s a source of so called theorems for free. One of those theorems says that, if there is an implementation of fmap for a given type constructor, one that preserves identity, then it must be unique.

Covariant and Contravariant Functors

Now that we’ve reviewed the writer functor, let’s go back to the reader functor. It was based on the partially applied function-arrow type constructor:

(->) r

We can rewrite it as a type synonym:

type Reader r a = r -> a

for which the Functor instance, as we’ve seen before, reads:

instance Functor (Reader r) where

fmap f g = f . g

But just like the pair type constructor, or the Either type constructor, the function type constructor takes two type arguments. The pair and Either were functorial in both arguments — they were bifunctors. Is the function constructor a bifunctor too?

Let’s try to make it functorial in the first argument. We’ll start with a type synonym — it’s just like the Reader but with the arguments flipped:

type Op r a = a -> r

This time we fix the return type, r, and vary the argument type, a. Let’s see if we can somehow match the types in order to implement fmap, which would have the following type signature:

fmap :: (a -> b) -> (a -> r) -> (b -> r)

With just two functions taking a and returning, respectively, b and r, there is simply no way to build a function taking b and returning r! It would be different if we could somehow invert the first function, so that it took b and returned a instead. We can’t invert an arbitrary function, but we can go to the opposite category.

A short recap: For every category C there is a dual category Cop. It’s a category with the same objects as C, but with all the arrows reversed.

Consider a functor that goes between Cop and some other category D:

F :: Cop → D

Such a functor maps a morphism fop :: a → b in Cop to the morphism F fop :: F a → F b in D. But the morphism fop secretly corresponds to some morphism f :: b → a in the original category C. Notice the inversion.

Now, F is a regular functor, but there is another mapping we can define based on F, which is not a functor — let’s call it G. It’s a mapping from C to D. It maps objects the same way F does, but when it comes to mapping morphisms, it reverses them. It takes a morphism f :: b → a in C, maps it first to the opposite morphism fop :: a → b and then uses the functor F on it, to get F fop :: F a → F b.

Considering that F a is the same as G a and F b is the same as G b, the whole trip can be described as:

G f :: (b → a) → (G a → G b)

It’s a “functor with a twist.” A mapping of categories that inverts the direction of morphisms in this manner is called a contravariant functor. Notice that a contravariant functor is just a regular functor from the opposite category. The regular functors, by the way — the kind we’ve been studying thus far — are called covariant functors.

Here’s the typeclass defining a contravariant functor (really, a contravariant endofunctor) in Haskell:

class Contravariant f where

contramap :: (b -> a) -> (f a -> f b)

Our type constructor Op is an instance of it:

instance Contravariant (Op r) where

-- (b -> a) -> Op r a -> Op r b

contramap f g = g . f

Notice that the function f inserts itself before (that is, to the right of) the contents of Op — the function g.

The definition of contramap for Op may be made even terser, if you notice that it’s just the function composition operator with the arguments flipped. There is a special function for flipping arguments, called flip:

flip :: (a -> b -> c) -> (b -> a -> c) flip f y x = f x y

With it, we get:

contramap = flip (.)

Profunctors

We’ve seen that the function-arrow operator is contravariant in its first argument and covariant in the second. Is there a name for such a beast? It turns out that, if the target category is Set, such a beast is called a profunctor. Because a contravariant functor is equivalent to a covariant functor from the opposite category, a profunctor is defined as:

Cop × D → Set

Since, to first approximation, Haskell types are sets, we apply the name Profunctor to a type constructor p of two arguments, which is contra-functorial in the first argument and functorial in the second. Here’s the appropriate typeclass taken from the Data.Profunctor library:

class Profunctor p where dimap :: (a -> b) -> (c -> d) -> p b c -> p a d dimap f g = lmap f . rmap g lmap :: (a -> b) -> p b c -> p a c lmap f = dimap f id rmap :: (b -> c) -> p a b -> p a c rmap = dimap id

All three functions come with default implementations. Just like with Bifunctor, when declaring an instance of Profunctor, you have a choice of either implementing dimap and accepting the defaults for lmap and rmap, or implementing both lmap and rmap and accepting the default for dimap.

Now we can assert that the function-arrow operator is an instance of a Profunctor:

instance Profunctor (->) where dimap ab cd bc = cd . bc . ab lmap = flip (.) rmap = (.)

Profunctors have their application in the Haskell lens library. We’ll see them again when we talk about ends and coends.

The Hom-Functor

The above examples are the reflection of a more general statement that the mapping that takes a pair of objects a and b and assigns to it the set of morphisms between them, the hom-set C(a, b), is a functor. It is a functor from the product category Cop×C to the category of sets, Set.

Let’s define its action on morphisms. A morphism in Cop×C is a pair of morphisms from C:

f :: a'→ a g :: b → b'

The lifting of this pair must be a morphism (a function) from the set C(a, b) to the set C(a', b'). Just pick any element h of C(a, b) (it’s a morphism from a to b) and assign to it:

g ∘ h ∘ f

which is an element of C(a', b').

As you can see, the hom-functor is a special case of a profunctor.

Challenges

- Show that the data type:

data Pair a b = Pair a b

is a bifunctor. For additional credit implement all three methods of

Bifunctorand use equational reasoning to show that these definitions are compatible with the default implementations whenever they can be applied. - Show the isomorphism between the standard definition of

Maybeand this desugaring:type Maybe' a = Either (Const () a) (Identity a)

Hint: Define two mappings between the two implementations. For additional credit, show that they are the inverse of each other using equational reasoning.

- Let’s try another data structure. I call it a

PreListbecause it’s a precursor to aList. It replaces recursion with a type parameterb.data PreList a b = Nil | Cons a b

You could recover our earlier definition of a

Listby recursively applyingPreListto itself (we’ll see how it’s done when we talk about fixed points).Show that

PreListis an instance ofBifunctor. - Show that the following data types define bifunctors in

aandb:data K2 c a b = K2 c

data Fst a b = Fst a

data Snd a b = Snd b

For additional credit, check your solutions agains Conor McBride’s paper Clowns to the Left of me, Jokers to the Right.

- Define a bifunctor in a language other than Haskell. Implement

bimapfor a generic pair in that language. - Should

std::mapbe considered a bifunctor or a profunctor in the two template argumentsKeyandT? How would you redesign this data type to make it so?

Next: Function Types.

Acknowledgment

As usual, big thanks go to Gershom Bazerman for reviewing this article.

Follow @BartoszMilewski

February 23, 2015 at 8:04 am

Reblogged this on Jarek Przygódzki. Blog programisty.

March 11, 2015 at 9:36 am

We are patiently waiting for next chunk of wisdom. I think it will be natural transformations and monads from CT point of view.

March 13, 2015 at 1:08 pm

[…] given the mapping h from z' to z, is a mapping from z'×a to z×a. And now, after discussing the functoriality of the product, we know how to do it. Because the product itself is a functor (more precisely an endo-bi-functor), […]

March 29, 2015 at 7:04 pm

Can be List rewritten in terms of Either like Maybe?

March 29, 2015 at 9:29 pm

List is a recursive data structure, so it’s a little more involved than that. The usual way of defining recursive data structures is to define a functor, in this case:

which is not recursive but it has a free type parameter

ainserted in place of recursion (here, in place of the tail). This part can be rewritten in terms ofEither, etc. A recursive list is then defined as a fixed point of this functor. See my posts about algebras.April 7, 2015 at 10:33 pm

Can I say that a TriFunctor where (a -> x) -> (b -> y) -> (c -> z) -> f a b c -> f x y z , is isomorphic to combination of Bifunctor with Functor ?

April 8, 2015 at 5:35 pm

What do you mean by “combination”?

April 8, 2015 at 9:18 pm

Is it correct to say that such TriFunctor is isomorphic to Functor which receives a tuple of 3 values or a Bifunctor which receives a tuple with 2 values as first argument and a single value as a second argument ?

April 9, 2015 at 10:27 am

I don’t have a formal proof but the intuition is that functors are morphisms in the category of (small) categories Cat (see my blog post on natural transformation for more details), which is cartesian closed. It means that it supports products and currying. So a trifunctor is just a functor that returns a bifunctor.

This is definitely true in Haskell, where type constructors are curried, and

trimapmay be implemented in terms of map and bimap.June 5, 2015 at 1:34 am

I’ve noticed small error in the declaration section of the Contravariant instance of the Op type. So I guess it would be better to:

1). Rename Op b to Op r in the first line.

2). Set correct concrete types in the comment.

3). (optional) Add one more comment with type, where Ops are replaced with the ‘real’ function types (Op r a = a -> r).

Then this section will look like:

instance Contravariant (Op r) where

— (b -> a) -> Op r a -> Op r b =

— = (b -> a) -> (a->r) -> (b->r)

contramap f g = g . f

Now it looks more clearly to me, don’t it?

June 5, 2015 at 6:21 pm

@karkunov: Good catch! Fixed it!

The full Haskell example would use

newtypeand pattern matching, but I didn’t want to obscure the simple point.newtype Op r a = Op (a -> r) instance Contravariant (Op r) where -- (b -> a) -> Op r a -> Op r b contramap f (Op g) = Op (g . f)July 15, 2015 at 12:11 pm

you wrote : “If you’re getting a little lost, try applying BiComp to Either, Const (), Identity, a, and b, in this order.” I found const () to be the wrong type and had to bind instead to (

const()). Thus:let x = BiComp (either (

const()) id)July 15, 2015 at 12:12 pm

imagine I have backticks around my const expression

July 15, 2015 at 1:16 pm

What I meant is this:

September 16, 2015 at 1:50 pm

thank you, Bartosz, for this masterpiece of clarity.

December 10, 2016 at 5:06 am

It looks like that there’s a slight mistake in the definition of

Bifunctor. The definition of thesecondfunction seems to be a typo. If I understand well, then: instead ofsecond = bimap idit should besecond = bimap id h.The problem seems to appear in the original Haskell source as well (ie. Control.Bifunctor v.0.44.4).

December 10, 2016 at 10:04 am

@Gyula Csom: Notice that the original Haskell source compiles, so the compiler understands it. You can look at

bimapas a function of three arguments, or a function of two arguments returning a function of one argument, or a function of one argument returning a function of two arguments:It’s the latter interpretation that makes this code work. It’s just currying.

December 10, 2016 at 3:07 pm

Thanks for your reply!

I’ve got it:-) Also I’ve caught my mistake. There’s no argument in the declaration of

second. That is: this would be mistaken:second h = bimap id. But the declaration is different:second = bimap idand this works through currying as you pointed.November 1, 2017 at 5:20 am

Hi Bartosz,

Great article (and series).

In the “Functorial Algebraic Data Types” section of the post, could it be possible that when you say (quote):

then the final result is of the type

bf (fu a') (gu b'):you meant?:

then the final result is of the type

bf (fu a') (gu b'):Thanks for the series.

November 1, 2017 at 8:34 am

You’re right. Fixed!

March 20, 2018 at 1:49 am

Hi Bartosz,

Sorry to bother you again but I still have doubts about the type signature of the bimap function of BiComp. According to the text, it is this one:

bimap :: (fu a -> fu a’) -> (gu b -> gu b’)

-> bf (fu a) (gu b) -> bf (fu a’) (gu b’)

My doubts come from the definition of bimap:

instance (Bifunctor bf, Functor fu, Functor gu) =>

Bifunctor (BiComp bf fu gu) where

bimap f1 f2 (BiComp x) = BiComp ((bimap (fmap f1) (fmap f2)) x)

And the type signatures provided for f1 and f2:

f1 :: a -> a’

f2 :: b -> b’

Taking this two into account, shouldn’t the type signature of bimap be?

bimap :: (a -> a’) -> (b -> b’)

-> bf (fu a) (gu b) -> bf (fu a’) (gu b’)

Thanks and kind regards.

March 20, 2018 at 5:53 am

I see how it could be confusing: there are two different bimaps, one for

bfand one forBiComp. I’ll add a subscript to it to clarify this point.May 4, 2018 at 2:13 am

Hi Bartosz, the comment about separate functoriality being equivalent to bifunctoriality is (perhaps surprisingly) incorrect without an extra condition on the two actions. This is sometimes used to model evaluation order (see work on “Premonoidal Categories” and “Freyd Categories”).

I put an explanation on the nlab: https://ncatlab.org/nlab/show/funny+tensor+product#separate_functoriality

May 6, 2018 at 6:59 pm

It is indeed surprising, but it makes sense. In principle the two maps don’t have to commute. I’ll have to fix it. Thanks for catching this!

June 24, 2018 at 4:37 am

You mentioned

“We can’t invert an arbitrary function, but we can go to the opposite category”

when discussing the contravariant functor but wouldn’t picking a morphism from C^op be an inverted function in the category Hask?

I’ve learned so much from you, thanks!

June 24, 2018 at 10:35 am

Don’t think of a morphism in Haskop as a function. Think of it as an arrow from a to b with a note attached to it, “For instructions how to use me, look at the corresponding function from b to a in Hask.”

August 5, 2018 at 1:36 pm

As of ghc 8.0.2 I found Bifunctor defined in Data.Bifunctor and not Control.Bifunctor.

February 20, 2019 at 6:50 am

Hi,

Thank you for such a great article.

I am trying to wrap my head around the idea of Profunctors, but it is hard for me. It appears to me that the idea of Profunctors is some sort of a generalization of plain old functions, like you can compose functions placing them before or after other functions, Profunctors allow do similar things, like if a Profunctor needs to be prepended with something then its contravariant part (lmap) is used, if it needs to prepend something else then its covariant part (rmap) is used. Correct me if I am wrong, please.

Also I can’t understand how the definition of Profunctor maps to it’s typeclass definition in Haskell, could you please elaborate on it?

February 20, 2019 at 9:33 am

There is a way of looking at profunctors as generalized hom-sets. You put the two categories C and D side by side. You have morphisms in C and morphisms in D. A profunctor p provides morphisms from C to D. For every pair of objects c and d, it produces a set, which acts like a hom-set between c and d. The elements of this set are called heteromorphisms. You can compose morphisms with heteromorphisms using lmap and rmap to get other heteromorphisms.

If you understand Haskell definition of a functor as lifting a morphism, a profunctor lifts a pair of morphisms.

February 20, 2019 at 9:55 am

Thank you, that is a great explanation. Not everything is clear for me now, but you gave me a new perspective.

BTW, my understanding of the Functor typeclass in Haskell is that Functor preserves a structure: if there is a morphism in the source category there has to be a corresponding morphism in the target category. Is there a better way to look at it in order to understand Profunctors?

February 20, 2019 at 10:49 am

Indeed, you can think of a product category C^op x D and having pairs of objects as objects and pairs of morphisms (the first going backwards) as morphisms. Then a profunctor preserves the structure given by those pairs of morphisms.

April 22, 2019 at 1:34 pm

Does every category have an opposite category? Or more precisely can we invert every morphism in eery category because for example if the objects represent sets and the function between two object is surjective then obviously inverting the arrow shouldn’t be possible because in that case the function would assign two different values to a single argument!

April 22, 2019 at 4:12 pm

Opposite category always exists. It’s obtained by formally reversing arrows, not by using inverse morphisms. A morphism from a to b in Setop is not an inverse of a function from b to a. It’s the same function, but with source and target renamed. It’s just a formal trick for defining contravariant functors.

April 22, 2019 at 11:13 pm

Thanks Bartosz but I’m a bit confused. If change of arrows do not represent inverting morphisms then what do arrows represent? Aren’t they used to indicate the domain and codomain of a morphism?

April 23, 2019 at 8:24 am

That’s the thing: they don’t have to represent anything other than the laws of composition.

April 23, 2019 at 10:08 pm

So let’s assume we can look under the hood and check the content of the objects.

And also assume we have two morphisms f and g as follow going from object A to B and from B to C respectively.

f:

A B

— —

1 ‘a’

2 ‘b’

3 ‘a’

g:

B C

— —

‘a’ true

‘b’ false

Is it correct to say that both g.f and f’.g’ in it’s opposite category map A’s content to C’s content as follow:

1 true

2 false

3 true

Which means the mapping is intact when going from a category to its opposite. It is just the composition order that changes!

April 24, 2019 at 11:30 am

If you carefully distinguish between the morphism and the underlying function (going in the opposite direction), than you’re correct.

May 19, 2019 at 12:56 pm

Hi Bartosz,

Quoting a paragraph of this chapter:

“But an easier way to think about bifunctors is that they are functors in both arguments. So instead of translating functorial laws — associativity and identity preservation — from functors to bifunctors, it’s enough to check them separately for each argument. If you have a mapping from a pair of categories to a third category, and you prove that it is functorial in each argument separately (i.e., keeping the other argument constant), then the mapping is automatically a bifunctor. By functorial I mean that it acts on morphisms like an honest functor.”

I think this is false & a bit misleading, based on the “separate functioriality” distinction already mentioned in a previous comment. I see you later mention that you need first f . second g = second g . first f in arbitrary categories, but that comes a bit later, and the statement here “it’s enough to check them separately for each argument” is made about arbitrary bifunctors & is not true. I think the paragraph could use some kind of revision, or to move it to later to only talk about bifunctors in Haskell.

Actually, it would be nice to point out a case where bifunctoriality breaks down in an arbitrary category, but I guess this would require talking about categories of effects or some such, where the order of morphisms matters much more.

Best,

Sofia

June 11, 2019 at 1:17 pm

@Sofia: Fixed, thank you!

July 20, 2019 at 4:34 pm

“first and second, are the two fmaps witnessing the functoriality of f in the first and the second argument, respectively.”

Is this correct? My understanding is that

secondonly witnesses the functoriality ofbimap id, i.e.,bimap id (g . g') = bimap id g . bimap id g'. But in order to say “bimap is functorial in the second argument”, one has to show thatbimap fis functorial for all f. Or am I misunderstanding it?July 21, 2019 at 12:28 am

I’m talking about the functoriality of f when one of the arguments is fixed. Bimap itself is not a functor, it’s a function.

August 20, 2019 at 8:35 am

Hi,

Thank you for such a great article.

I have a question about profunctor:

In the book, you said “It turns out that, if the target category is 𝐒𝐞𝐭, such a beast is called a profunctor.”

But why profunctor must be related to 𝐒𝐞𝐭?

For bifunctor, we use C x D -> E.

For profunctor, why we use C^op x D -> Set, instead of C^op x D -> E ?

August 20, 2019 at 12:51 pm

It’s a definition. There is nothing wrong with a functor C^op x D -> E. It’s just not called a profunctor.

August 20, 2019 at 10:26 pm

But why the definition of profunctor must use 𝐒𝐞𝐭?

The 𝐒𝐞𝐭 category means every object in 𝐒𝐞𝐭 must be treated as a set. This involves set theory. (For example, we may look into the internal elements of the set).

But…as you said, we don’t like set theory. In category theory, we should treat object as atomic point and use morphisms to represent information.

Back to the question:

If I said that “a profunctor from C and D to Set is exactly a functor from C^op x D to Set”, is this correct or wrong?

If it is correct, why I can’t say that “a profunctor from C and D to E is exactly a functor from C^op x D to E”?

I don’t know exactly where set theory have to be used in these case.

August 21, 2019 at 4:07 am

There are several constructions in category theory that treat Set as a special case (another one is presheaves, functors from C^op to Set). They are singled out because of their usefulness. Profunctors use Set because they generalize hom-sets.

BTW, in enriched categories, you can define profunctors that map into a monoidal category. But that’s again because hom-sets in enriched categories are replaced with objects from some monoidal category.

November 25, 2019 at 6:19 am

I can’t fully comprehend how come

id :: a -> afits first argument of(>=>)infmap f = id >=> return . f, which isa -> Writer a. If I put it into repl I get an error:also it is strange to see

>=>in fmap, can’t it befmap f = return .f?November 25, 2019 at 7:02 am

When you write

z::a->Writer b, this is interpreted asz::forall a b. a->Writer bandiddoesn’t fit this signature.Notice that

fmap fgoes fromWriter atoWriter b.idtakes it fromWriter atoWriter a, which is a legitimate argument to>=>.December 19, 2019 at 5:31 am

Hi Bartosz,

Thank you for the great article!

I have a question about the 3 functions(bimap, first, second) in Bifunctor typeclass and how they are evaluated. If bimap is evaluated to first and second, which is in turn evaluated to bimap, how could this possibly arrive at a function from (f a b) to (f c d)? I tried expanding bimap on paper but just ended up with something like this:

bimap g h = first g . second h

= bimap g id . bimap id h

= first g . second id . first id . second h

= bimap g id . bimap id id . bimap id id . bimap id h

…

which seems to be expanding endlessly. Could you please explain how bimap should be evaluated?

December 20, 2019 at 1:38 pm

There is a Haskell pragma in the class definition of

Bimapthat prevents this circularity:{-# MINIMAL bimap | first, second #-}It informs the compiler that the implementer of the instance of

Bifunctormust either providebimaporfirstandsecond. The compiler then uses the remaining definitions to derive the remaining ones. You can also implement all three, if you can beat the performance of the default implementations.March 31, 2020 at 8:24 am

Hi Bartosz, thanks for this series.

I’ve a question, when you say: “because the two maps may not commute, that is first g . second h may not be the same as second h . first g”; Why it doesn’t commute? A tried with all Bifunctor defined into Data hHaskell and seems that using second h. first g , it works. Have you an example that doesn’t work? Thank in advance

March 31, 2020 at 9:26 am

There are categories in which it doesn’t work. https://ncatlab.org/nlab/show/premonoidal+category

April 1, 2020 at 9:55 am

Ok thanks, but in the Haskell type’s category is it commutative, right?

May 12, 2020 at 1:23 am

Hi Bartosz, thanks for this series! I have a question under Bifunctors.

I am not sure I understand why arrows are going from the individual categories C or D into E. I have been thinking if the arrow should be from the product category(CxD) to E.

April 3, 2021 at 11:19 pm

Hi, I found 2 other ways to define fmap for the Writer functor:

fmap f (a, s) = (f a, s)

fmap f (a, s) = ret (f a)

I think the 2nd one is not a functor, but is the 1st one equivalent to yours ?

Mine looks simpler on paper, but I feel yours shows some deeper connection I can’t quite grasp

Thanks for for all the material, it’s brilliant.

October 12, 2021 at 7:18 pm

Is there some connection between the “covariant” / “contravariant” here and the “covariant” / “contravariant” one would be familiar with from generics in OO languages? Is there somewhere I can read about this?

For example, in Python, Union and Tuple are covariant in the type arguments, most immutable containers, like Sequence, are covariant, but Callables are contravariant in the argument types and covariant in the return type. This seems to line up in some way with the functoriality of algebraic data types here, but I have no idea how to think about this “subtype” relationship.

October 13, 2021 at 12:28 pm

Mike: Yes, there is a connection but in a different category. The subtype relation itself can be considered an arrow in a thin category (a poset). You interpret a->b as ‘a’ is a subtype of ‘b’. Contravariant type constructors flip this arrow. A contravariant functor F will satisfy Fb->Fa, that is Fb is a subtype of Fa. See “Orders” in https://bartoszmilewski.com/2014/12/05/categories-great-and-small/

September 27, 2022 at 7:41 am

Hi bartosz, I had a doubt. I have an intution for bifunctor f in haskell taking a and b as type parameter that f is a container for some algebraic datatype based on a and b (i.e, built using product and sum types) and bimap operates on all those objects in container (just like functors). Is this intution correct?

September 27, 2022 at 7:57 am

In most cases, yes. But it’s also possible to come up with weird examples like this: