Previously: Identity Types.

Let me first explain why the naive categorical model of dependent types doesn’t work very well for identity types. The problem is that, in such a model, any arrow can be considered a fibration, and therefore interpreted as a dependent type. In our definition of path induction, with an arrow that makes the outer square commute, there are no additional constraints on

:

So we are free to substitute for

, and use the identity for

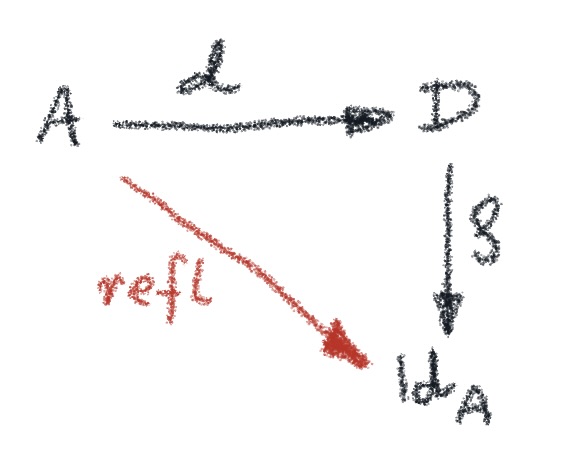

:

We are guaranteed that there is a unique that makes the two triangles commute. But these commutation conditions tell us that

is the inverse of

and, consequently,

is isomorphic to

. It means that there are no paths in

other than those given by reflexivity.

This is not satisfactory from the point of homotopy type theory, since the existence of non-trivial paths is necessary to make sense of things like higher inductive types (HITs) or univalence. If we want to model dependent types as fibrations, we cannot allow to be a fibration. Thus we need a more restrictive model in which not all mappings are fibrations.

The solution is to apply the lessons from topology, in particular homotopy. Recall that maps between topological spaces can be characterized as fibrations, cofibrations, and homotopy equivalences. There usually are overlaps between these three categories.

A fibration that is also an equivalence is called a trivial fibration or an acyclic fibration. Similarly, we have trivial (acyclic) cofibrations. We’ve also seen that, roughly speaking, cofibrations generalize injections. So, if we want a non-trivial model of identity types, it makes sense to model as a cofibration. We want different values

to be mapped to different “paths”

, and we’d also like to have some non-trivial paths left over to play with.

We know what a path is in a topological space : it’s a continuous mapping from a unit interval,

. In a cartesian category with weak equivalences, we can use an abstract definition of the object representing the space of all paths in

. A path space object

is an object that factorizes the diagonal morphism

, such that

is a weak equivalence.

In a category that supports a factorization system, we can tighten this definition by requiring that be a fibration, defining a good path object; and

be a cofibration (therefore a trivial cofibration) defining a very good path object.

The intuition behind this diagram is that produces the start and the end of a path, and

sends a point to a constant path.

Compare this with the diagram that illustrates the introduction rule for the identity type:

We want to be a trivial cofibration, that is a cofibration that’s a weak homotopy equivalence. Weak equivalence let us shrink all paths. Imagine a path as a rubber band. We fix one end and of the path and let the other end slide all the way back until the path becomes constant. (In the compact/open topology of

, this works also for closed loops.)

Thus the existence of very good path objects takes care of the introduction rule for identity types.

The elimination rule is harder to wrap our minds around. How is it possible that any mapping that is defined on trivial paths, which are given by over the diagonal of

, can be uniquely extended to all paths?

We might take a hint from complex analysis, where we can uniquely define analytic continuations of real function.

In topology, our continuations are restricted by continuity. When you are lifting a path in , you might not have much choice as to which value of type

to pick next. In fact, there might be only one value available to you — the “closest one” in the direction you’re going. To choose any other value, you’d have to “jump,” which would break continuity.

You can visualize building by growing it from its initial value

. You gradually extend it above the path

until you reach the point directly above

. (In fact, this is the rough idea behind cubical type theory.)

A more abstract way of putting it is that identity types are path spaces in some factorization system, and dependent types over them are fibrations that satisfy the lifting property. Any path from to

in

has a unique lifting

in

that starts at

.

This is exactly the property illustrated by the lifting diaram, in which paths are elements of the identity type :

This time is not a fibration.

The general framework, in which to build models of homotopy type theory is called a Quillen model category, which was originally used to model homotopies in topological spaces. It can be described as a weak factorization system, in which any morphism can be written as a trivial cofibration followed by a fibration. It must satisfy the unique lifting property for any square in which is a cofibration,

is a fibration, and one of them is a weak equivalence:

The full definition of a model category has more moving parts, but this is the gist of it.

We model dependent types as fibrations in a model category. We construct path objects as factorizations of the diagonal, and this lets us define non-trivial identity types.

One of the consequences of the fact that there could be multiple identity paths between two points is that we can, in turn, compare these paths for equality. There is, for instance, an identity type of identity types . Such iterated types correspond to higher homotopies: paths between paths, and so on, ad infinitum. The structure that arises is called a weak infinity groupoid. It’s a category in which every morphism has an inverse (just follow the same path backwards), and category laws (identity or associativity) are satisifed up to higher morphisms (higher homotopies).