Proviously Sieves and Sheaves.

We have seen how topology can be defined by working with sets of continuous functions over coverages. Categorically speaking, a coverage is a special case of a sieve, which is defined as a subfunctor of the hom-functor  .

.

We’d like to characterize the relationship between a functor and its subfunctor by looking at them as objects in the category of presheaves. For that we need to introduce the idea of a subobject.

We’ll start by defining subobjects in the category of sets in a way that avoids talking about elements. Here we have two options.

The first one uses a characteristic function. It’s a predicate that answers the question: Is some element  a member of a given subset or not? Notice that any Boolean-valued function uniquely defines a subset of its domain, so we don’t really need to talk about elements, just a function.

a member of a given subset or not? Notice that any Boolean-valued function uniquely defines a subset of its domain, so we don’t really need to talk about elements, just a function.

But we still have to define a Boolean set. Let’s call this set  , and designate one of its element as “True.” Selecting “True” can be done by defining a function

, and designate one of its element as “True.” Selecting “True” can be done by defining a function  , where

, where  is the terminal object (here, a singleton set). In principle we should insist that

is the terminal object (here, a singleton set). In principle we should insist that  contains two elements, “True” and “False,” but that would make it more difficult to generalize.

contains two elements, “True” and “False,” but that would make it more difficult to generalize.

The second way to define a subset  is to provide an injective function

is to provide an injective function  that embeds

that embeds  in

in  . Injectivity guarantees that no two elements are mapped to the same element. The image of

. Injectivity guarantees that no two elements are mapped to the same element. The image of  then defines the subset of

then defines the subset of  . In a general category, injective functions are replaced by monics (monomorphisms).

. In a general category, injective functions are replaced by monics (monomorphisms).

Notice that there can be many injections that define the same subset. It’s okay for them to permute the image of  as long as it covers exactly the same subset of

as long as it covers exactly the same subset of  . (These injections form an equivalence class.)

. (These injections form an equivalence class.)

The fact that the two definitions coincide can be summarized by one commuting diagram. In the category of sets, given a characteristic function  , the subset

, the subset  and the monic

and the monic  are uniquely (up to isomorphism) defined as a pullback of this diagram.

are uniquely (up to isomorphism) defined as a pullback of this diagram.

We can now turn the tables and use this diagram to define the object  called the subobject classifier, together with the monic

called the subobject classifier, together with the monic  . We do it by means of a universal construction. We postulate that: For every monic

. We do it by means of a universal construction. We postulate that: For every monic  between two arbitrary objects there exist a unique arrow

between two arbitrary objects there exist a unique arrow  such that the above diagram constitutes a pullback.

such that the above diagram constitutes a pullback.

This is a slightly unusual definition. Normally we think of a pullback as defining the northwest part of the diagram given its southeast part. Here, we are solving a sudoku puzzle, trying to fill the southeast part to uniquely complete a pullback diagram.

Let’s see how this works for sets. To construct a pullback (a.k.a., a fibered product  ) we first create a set of pairs

) we first create a set of pairs  where

where  and

and  (the only element of the singleton set). But not all

(the only element of the singleton set). But not all  ‘s are acceptable, because we have a pullback condition, which says that

‘s are acceptable, because we have a pullback condition, which says that  , where

, where  is the element of

is the element of  pointed to by

pointed to by  . This tells us that

. This tells us that  is isomorphic to the subset of

is isomorphic to the subset of  for which

for which  is

is  .

.

The question is: What happens to the other elements of  ? They cannot be mapped to

? They cannot be mapped to  , so

, so  must contain at least one more element (in case

must contain at least one more element (in case  is not an isomorphism). Can it contain more?

is not an isomorphism). Can it contain more?

This is where the universal construction comes into play. Any monic  (here, an injective function) must uniquely determine a

(here, an injective function) must uniquely determine a  that completes the pullback. In particular, we can pick

that completes the pullback. In particular, we can pick  to be a singleton set and

to be a singleton set and  to be a two-element set. We see that if

to be a two-element set. We see that if  contained only

contained only  and nothing else, no

and nothing else, no  would complete the pullback. And if

would complete the pullback. And if  contained more than two elements, there would be not one but at least two such

contained more than two elements, there would be not one but at least two such  ‘s. So, by the Goldilock principle,

‘s. So, by the Goldilock principle,  must have exactly two elements.

must have exactly two elements.

We’ll see later that this is not necessarily true in a more general category.

Next: Subfunctor Classifier.

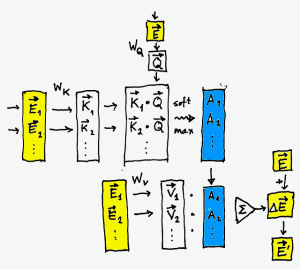

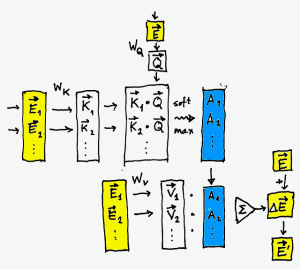

There are many excellent AI papers and tutorials that explain the attention pattern in Large Language Models. But this essentially simple pattern is often obscured by implementation details and optimizations. In this post I will try to cut to the essentials.

In a nutshell, the attention machinery tries to get at a meaning of a word (more precisely, a token). This should be easy in principle: we could just look it up in the dictionary. For instance, the word “triskaidekaphobia” means “extreme superstition regarding the number thirteen.” Simple enough. But consider the question: What does “it” mean in the sentence “look it up in the dictionary”? You could look up the word “it” in the dictionary, but that wouldn’t help much. More ofthen than not, we guess the meaning of words from their context, sometimes based on a whole conversation.

The attention mechanism is a way to train a language model to be able to derive a meaning of a word from its context.

The first step is the rough encoding of words (tokens) as multi-dimensional vectors. We’re talking about 12,288 dimensions for GPT-3. That’s an enormous semantic space. It means that you can adjust the meaning of a word by nudging it in thousands of different directions by varying amounts (usually 32-bit floating point numbers). This “nudging” is like adding little footnotes to a word, explaining what was its precise meaning in a particular situation.

(Note: In practice, working with such huge vectors would be prohibitively expensive, so they are split between multiple heads of attention and processed in parallel. For instance, GPT-3 has 96 heads of attention, and each head works within a 128-dimensional vector space.)

We are embedding the input word as a 12,288-dimensional vector  , and we are embedding

, and we are embedding  words of context as 12,288-dimensional vectors,

words of context as 12,288-dimensional vectors,  ,

,  (for GPT-3,

(for GPT-3,  tokens). Initially, the mapping from words to embeddings is purely random, but as the training progresses, it is gradually refined using backpropagation.

tokens). Initially, the mapping from words to embeddings is purely random, but as the training progresses, it is gradually refined using backpropagation.

(Note: In most descriptions, you’ll see a whole batch of words begin embedded all at once, and the context often being identical with that same batch–but this is just an optimization.)

The goal is to refine the embedding  by adding to it a small delta

by adding to it a small delta  that is derived from the context

that is derived from the context  .

.

This is usually described as the vector  querying the context, and the context responding to this query.

querying the context, and the context responding to this query.

First, we apply a gigantic trainable 12,288 by 12,288 matrix  to the embedding

to the embedding  , to get the query vector:

, to get the query vector:

You may think of  as the question: “Who am I with respect to the Universe?” The entries in the matrix

as the question: “Who am I with respect to the Universe?” The entries in the matrix  are the weights that are learned by running the usual backpropagation.

are the weights that are learned by running the usual backpropagation.

We then apply another trainable matrix  to every vector

to every vector  of the context to get a batch of key vectors:

of the context to get a batch of key vectors:

You may think of  as a possible response from the

as a possible response from the  ‘th component of the context to all kinds of questions.

‘th component of the context to all kinds of questions.

The next step is crucial: We calculate how relevant each element of the context is to our word. In other words, we are focusing our attention on particular elements of the context. We do it by taking  scalar products

scalar products  .

.

A scalar product can vary widely. A large positive number means that the  ‘th element of the context is highly relevant to the meaning of

‘th element of the context is highly relevant to the meaning of  . A large negative number, on the other hand, means that it has very little to contribute.

. A large negative number, on the other hand, means that it has very little to contribute.

What we really need is to normalize these numbers to a range between zero (not relevant) and one (extremely relevant) and make sure that they all add up to one. This is normally done using the softmax procedure: we first raise  to the power of the given number to make the result non-negative:

to the power of the given number to make the result non-negative:

We then divide it by the total sum, to normalize it:

These are our attention weights. (Note: For efficiency, before performing the softmax, we divide all numbers by the square root of the dimension of the vector space  .)

.)

Attention weights tell us how much each element of the context can contribute to the meaning of  , but we still don’t know what it contributes. We figure this out by multiplying each element of the context by yet another trainable matrix,

, but we still don’t know what it contributes. We figure this out by multiplying each element of the context by yet another trainable matrix,  . The result is a batch of value vectors

. The result is a batch of value vectors  :

:

We now accumulate all these contribution, weighing them by their attention weights  . We get the adjusted meaning of our original embedding

. We get the adjusted meaning of our original embedding  (this step is called the residual connection):

(this step is called the residual connection):

The result  is infused with the additional information gained from a larger context. It’s closer to the actual meaning. For instance, the word “it” would be nudged towards the noun that it stands for.

is infused with the additional information gained from a larger context. It’s closer to the actual meaning. For instance, the word “it” would be nudged towards the noun that it stands for.

And that’s essentially the basic block of the attention system. The rest is just optimization and composition.

One major optimization is gained by processing a whole window of tokens at once (2048 tokens for GPT-3). In particular, in the self-attention pattern we use the same batch of tokens for both the input and the context. In general, though, the context can be distinct from the input. It could, for instance, be a sentence in a different language.

Another optimization is the partitioning of all three vectors,  ,

,  , and

, and  between the heads of attention. Each of these heads operates inside a smaller subspace of the vector space. For GPT-3 these are 128-dimensional subspaces. The heads produce smaller-dimensional deltas,

between the heads of attention. Each of these heads operates inside a smaller subspace of the vector space. For GPT-3 these are 128-dimensional subspaces. The heads produce smaller-dimensional deltas,  , which are concatenated into larger vectors, which are then added to the original embeddings through residual connection.

, which are concatenated into larger vectors, which are then added to the original embeddings through residual connection.

In GPT-3, each multi-headed attention block is followed by a multi-layer perceptron, MLP, and this transformation is repeated 96 times. Most steps in an LLM are just linear algebra; except for softmax and the activation function in the MLP, which are non-linear.

All this work is done just to produce the next word in a sentence.

.

a member of a given subset or not? Notice that any Boolean-valued function uniquely defines a subset of its domain, so we don’t really need to talk about elements, just a function.

, and designate one of its element as “True.” Selecting “True” can be done by defining a function

, where

is the terminal object (here, a singleton set). In principle we should insist that

contains two elements, “True” and “False,” but that would make it more difficult to generalize.

is to provide an injective function

that embeds

in

. Injectivity guarantees that no two elements are mapped to the same element. The image of

then defines the subset of

. In a general category, injective functions are replaced by monics (monomorphisms).

as long as it covers exactly the same subset of

. (These injections form an equivalence class.)

, the subset

and the monic

are uniquely (up to isomorphism) defined as a pullback of this diagram.

called the subobject classifier, together with the monic

. We do it by means of a universal construction. We postulate that: For every monic

between two arbitrary objects there exist a unique arrow

such that the above diagram constitutes a pullback.

) we first create a set of pairs

where

and

(the only element of the singleton set). But not all

‘s are acceptable, because we have a pullback condition, which says that

, where

is the element of

pointed to by

. This tells us that

is isomorphic to the subset of

for which

is

.

? They cannot be mapped to

, so

must contain at least one more element (in case

is not an isomorphism). Can it contain more?

(here, an injective function) must uniquely determine a

that completes the pullback. In particular, we can pick

to be a singleton set and

to be a two-element set. We see that if

contained only

and nothing else, no

would complete the pullback. And if

contained more than two elements, there would be not one but at least two such

‘s. So, by the Goldilock principle,

must have exactly two elements.