Previously (Weak) Homotopy Equivalences.

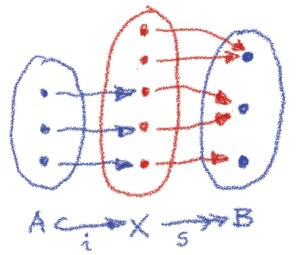

An average function between sets, is neither surjective nor injective. We can however isolate the two “failure modes” if we insert a third set

in between. We can, for instance, pick this set to be the subset of

that is the image of

under

. We then define

to be the surjective part of

. This way

deals just with all the non-injectivity of

. We can then follow

with an injective function

. We get the (Surj, Inj) factorization of an arbitrary function into a surjection followed by an injection:

This factorization is unique up to unique isomorphism.

Notice also that both surjections and injections are closed under composition and that every isomorphism is simultaneously a surjection and an injection.

In category theory we generalize this idea to define abstract factorization systems.

A (strict) factorization system specifies two classes of morphisms and

, satisfying conditions loosely analogous to the (Surj, Inj) factorization:

- Each class is closed under composition and contains all isomorphisms.

- Every morphism can be factorized,

, with

and

- The factorization is functorial.

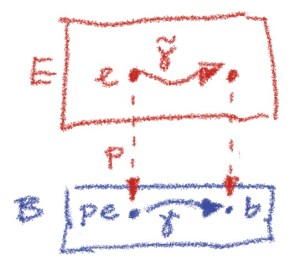

The last condition requires some explanation. We can look at factorization as a functor between two categories.

The source category is the arrow category of . Its objects are arrows or, more precisely, triples

. A morphism from

to

is a pair of arrows

that make the following square commute:

The target category is the category of factorizations. Its objects are factorizations, or pairs of composable arrows :

taken from the two classes . Morphisms are triples of arrows

that make the following diagram commute:

The functor in question maps an arrow to its factorization,

, with

. Its action on a morphism

is the commuting diagram above. For functoriality, we need the arrow

to be determined uniquely.

Notice that we can redraw the last diagram in such a way that crosses it diagonally.

In other words, morphisms in have the (strict) left lifting property with respect to morphisms in

.

Interesting things start happening when we relax the strictness property and allow not to be unique. We can no longer talk about functoriality of factorization. Instead we lean on the (weak) lifting property.

To illustrate this, let’s reverse the roles of surjections and injections in our factorization of functions. Indeed, every function can be factored into an injection followed by a surjection. Such (Inj, Surj) factorization is not unique. (It also requires the use of the Axiom of Choice.)

A weak factorization system consists, as before, of two classes of morphisms that allow for factoriziation of an arbitrary morphism

. This time, however, we postulate that

is precisely the class of morphisms with a left lifting property against every morphism in

; and vice versa for

and the right lifting property.

At this point you may recall the lifting property we discussed earlier between fibrations and cofibrations. In particular, a cofibration satisfies the homotopy extension property.

Interestingly, there is a connection between fibrations and surjections, and cofibrations and injections.

First, we’ll show that a fibration is a surjection as long as

is non empty and

is path connected.

Here’s the proof: If were not surjective then there would be a point

that is not in the image of

. Since

is not empty, there exists a point

. Take any path

in

connecting

to

. Since

is a fibration, we can lift this path to

in

. Since

projects the endpoint of

to

, we have reached a contradiction. Therefore

must be a surjection.

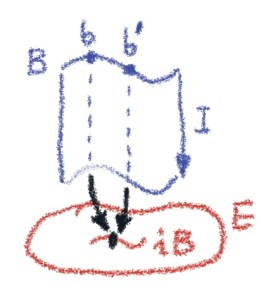

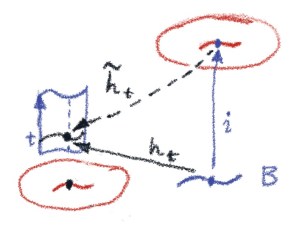

The proof that every cofibration is injective is a bit more involved. It uses a very handy notion of a mapping cylinder. We can visualize a function between two spaces as a bunch of wires. Each wire connects a point

to the corresponding point

. A mapping cylinder

is a topological space that formalizes this picture.

We start with pairs , where

is the unit segment, which we use to parameterize the length of each wire. Then we add the target

to our cylinder, and plug the end

of each wire to its “socket”

.

Formally, the mapping cylinder is a quotient space of the disjoint union

, identifying each

with

.

Notice that, if is not injective, there will be some merging of multiple wires right when they hit

, but not earlier–the fact that will become relevant later.

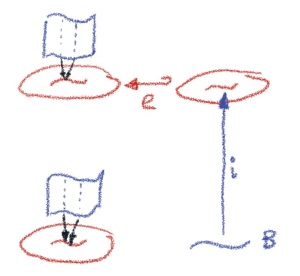

Now let’s use the cofibration property of . We replace the big space

with the cylinder

. The arrow

is the inclusion

. Notice that

will be identified with the starting point of the homotopy

that we’re constructing.

First we define the homotopy . For every

, we write

.

At ,

is the point in

that sits on the seam between

and

. In our quotient space, it corresponding to

.

For we define

. It reverses the direction of wires in the cylinder

. (We use curly braces to embed the pair

into the quotient

.)

The function is continuous, therefore a homotopy. (It may still merge multiple points into one, if

is not injective.)

Cofibration condition states that any homotopy can be lifted to

, such that

. The latter condition can be written as:

In our case, will shrink the whole of

down to

before embedding it in

.

Then, for any ,

will shrink

down to

, embed it in

at

, and inject it into

.

Notice that, for any fixed , our

is injective (

could only do the merging of wires at

, where the identification happens). But the lifting condition tells us that

. Therefore

must also be injective.

We have shown that fibrations between (path-connected, non-empty) topological spaces are surjective, and that cofibrations are injective.

Corresponding to the weak (Inj, Surj) factorization system in Set, we can build a weak (Cofib, Fib) factorization system in Top (the category of topological spaces). Indeed, under some conditions, every continuous function can be factored into a cofibration followed by a fibration.

We’ve seen earlier that cofibrations have the left lifting property with respect to fibrations, and vice versa. So (Cofib, Fib) is indeed an example of a weak factorization system. We’ll see later that weak factorization systems form the basis of Quillen model categories.

Next: Models of (Dependent) Type Theory.