This is part 22 of Categories for Programmers. Previously: Monads and Effects. See the Table of Contents.

If you mention monads to a programmer, you’ll probably end up talking about effects. To a mathematician, monads are about algebras. We’ll talk about algebras later — they play an important role in programming — but first I’d like to give you a little intuition about their relation to monads. For now, it’s a bit of a hand-waving argument, but bear with me.

Algebra is about creating, manipulating, and evaluating expressions. Expressions are built using operators. Consider this simple expression:

x2 + 2 x + 1

This expression is formed using variables like x, and constants like 1 or 2, bound together with operators like plus or times. As programmers, we often think of expressions as trees.

Trees are containers so, more generally, an expression is a container for storing variables. In category theory, we represent containers as endofunctors. If we assign the type a to the variable x, our expression will have the type m a, where m is an endofunctor that builds expression trees. (Nontrivial branching expressions are usually created using recursively defined endofunctors.)

What’s the most common operation that can be performed on an expression? It’s substitution: replacing variables with expressions. For instance, in our example, we could replace x with y - 1 to get:

(y - 1)2 + 2 (y - 1) + 1

Here’s what happened: We took an expression of type m a and applied a transformation of type a -> m b (b represents the type of y). The result is an expression of type m b. Let me spell it out:

m a -> (a -> m b) -> m b

Yes, that’s the signature of monadic bind.

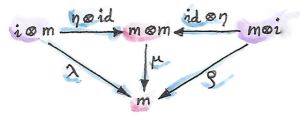

That was a bit of motivation. Now let’s get to the math of the monad. Mathematicians use different notation than programmers. They prefer to use the letter T for the endofunctor, and Greek letters: μ for join and η for return. Both join and return are polymorphic functions, so we can guess that they correspond to natural transformations.

Therefore, in category theory, a monad is defined as an endofunctor T equipped with a pair of natural transformations μ and η.

μ is a natural transformation from the square of the functor T2 back to T. The square is simply the functor composed with itself, T ∘ T (we can only do this kind of squaring for endofunctors).

μ :: T2 -> T

The component of this natural transformation at an object a is the morphism:

μa :: T (T a) -> T a

which, in Hask, translates directly to our definition of join.

η is a natural transformation between the identity functor I and T:

η :: I -> T

Considering that the action of I on the object a is just a, the component of η is given by the morphism:

ηa :: a -> T a

which translates directly to our definition of return.

These natural transformations must satisfy some additional laws. One way of looking at it is that these laws let us define a Kleisli category for the endofunctor T. Remember that a Kleisli arrow between a and b is defined as a morphism a -> T b. The composition of two such arrows (I’ll write it as a circle with the subscript T) can be implemented using μ:

g ∘T f = μc ∘ (T g) ∘ f

where

f :: a -> T b g :: b -> T c

Here T, being a functor, can be applied to the morphism g. It might be easier to recognize this formula in Haskell notation:

f >=> g = join . fmap g . f

or, in components:

(f >=> g) a = join (fmap g (f a))

In terms of the algebraic interpretation, we are just composing two successive substitutions.

For Kleisli arrows to form a category we want their composition to be associative, and ηa to be the identity Kleisli arrow at a. This requirement can be translated to monadic laws for μ and η. But there is another way of deriving these laws that makes them look more like monoid laws. In fact μ is often called multiplication, and η unit.

Roughly speaking, the associativity law states that the two ways of reducing the cube of T, T3, down to T must give the same result. Two unit laws (left and right) state that when η is applied to T and then reduced by μ, we get back T.

Things are a little tricky because we are composing natural transformations and functors. So a little refresher on horizontal composition is in order. For instance, T3 can be seen as a composition of T after T2. We can apply to it the horizontal composition of two natural transformations:

IT ∘ μ

and get T∘T; which can be further reduced to T by applying μ. IT is the identity natural transformation from T to T. You will often see the notation for this type of horizontal composition IT ∘ μ shortened to T∘μ. This notation is unambiguous because it makes no sense to compose a functor with a natural transformation, therefore T must mean IT in this context.

We can also draw the diagram in the (endo-) functor category [C, C]:

Alternatively, we can treat T3 as the composition of T2∘T and apply μ∘T to it. The result is also T∘T which, again, can be reduced to T using μ. We require that the two paths produce the same result.

Similarly, we can apply the horizontal composition η∘T to the composition of the identity functor I after T to obtain T2, which can then be reduced using μ. The result should be the same as if we applied the identity natural transformation directly to T. And, by analogy, the same should be true for T∘η.

You can convince yourself that these laws guarantee that the composition of Kleisli arrows indeed satisfies the laws of a category.

The similarities between a monad and a monoid are striking. We have multiplication μ, unit η, associativity, and unit laws. But our definition of a monoid is too narrow to describe a monad as a monoid. So let’s generalize the notion of a monoid.

Monoidal Categories

Let’s go back to the conventional definition of a monoid. It’s a set with a binary operation and a special element called unit. In Haskell, this can be expressed as a typeclass:

class Monoid m where

mappend :: m -> m -> m

mempty :: m

The binary operation mappend must be associative and unital (i.e., multiplication by the unit mempty is a no-op).

Notice that, in Haskell, the definition of mappend is curried. It can be interpreted as mapping every element of m to a function:

mappend :: m -> (m -> m)

It’s this interpretation that gives rise to the definition of a monoid as a single-object category where endomorphisms (m -> m) represent the elements of the monoid. But because currying is built into Haskell, we could as well have started with a different definition of multiplication:

mu :: (m, m) -> m

Here, the cartesian product (m, m) becomes the source of pairs to be multiplied.

This definition suggests a different path to generalization: replacing the cartesian product with categorical product. We could start with a category where products are globally defined, pick an object m there, and define multiplication as a morphism:

μ :: m × m -> m

We have one problem though: In an arbitrary category we can’t peek inside an object, so how do we pick the unit element? There is a trick to it. Remember how element selection is equivalent to a function from the singleton set? In Haskell, we could replace the definition of mempty with a function:

eta :: () -> m

The singleton is the terminal object in Set, so it’s natural to generalize this definition to any category that has a terminal object t:

η :: t -> m

This lets us pick the unit “element” without having to talk about elements.

Unlike in our previous definition of a monoid as a single-object category, monoidal laws here are not automatically satisfied — we have to impose them. But in order to formulate them we have to establish the monoidal structure of the underlying categorical product itself. Let’s recall how monoidal structure works in Haskell first.

We start with associativity. In Haskell, the corresponding equational law is:

mu (x, mu (y, z)) = mu (mu (x, y), z)

Before we can generalize it to other categories, we have to rewrite it as an equality of functions (morphisms). We have to abstract it away from its action on individual variables — in other words, we have to use point-free notation. Knowning that the cartesian product is a bifunctor, we can write the left hand side as:

(mu . bimap id mu)(x, (y, z))

and the right hand side as:

(mu . bimap mu id)((x, y), z)

This is almost what we want. Unfortunately, the cartesian product is not strictly associative — (x, (y, z)) is not the same as ((x, y), z) — so we can’t just write point-free:

mu . bimap id mu = mu . bimap mu id

On the other hand, the two nestings of pairs are isomorphic. There is an invertible function called the associator that converts between them:

alpha :: ((a, b), c) -> (a, (b, c)) alpha ((x, y), z) = (x, (y, z))

With the help of the associator, we can write the point-free associativity law for mu:

mu . bimap id mu . alpha = mu . bimap mu id

We can apply a similar trick to unit laws which, in the new notation, take the form:

mu (eta (), x) = x mu (x, eta ()) = x

They can be rewritten as:

(mu . bimap eta id) ((), x) = lambda ((), x) (mu . bimap id eta) (x, ()) = rho (x, ())

The isomorphisms lambda and rho are called the left and right unitor, respectively. They witness the fact that the unit () is the identity of the cartesian product up to isomorphism:

lambda :: ((), a) -> a lambda ((), x) = x

rho :: (a, ()) -> a rho (x, ()) = x

The point-free versions of the unit laws are therefore:

mu . bimap eta id = lambda mu . bimap id eta = rho

We have formulated point-free monoidal laws for mu and eta using the fact that the underlying cartesian product itself acts like a monoidal multiplication in the category of types. Keep in mind though that the associativity and unit laws for the cartesian product are valid only up to isomorphism.

It turns out that these laws can be generalized to any category with products and a terminal object. Categorical products are indeed associative up to isomorphism and the terminal object is the unit, also up to isomorphism. The associator and the two unitors are natural isomorphisms. The laws can be represented by commuting diagrams.

Notice that, because the product is a bifunctor, it can lift a pair of morphisms — in Haskell this was done using bimap.

We could stop here and say that we can define a monoid on top of any category with categorical products and a terminal object. As long as we can pick an object m and two morphisms μ and η that satisfy monoidal laws, we have a monoid. But we can do better than that. We don’t need a full-blown categorical product to formulate the laws for μ and η. Recall that a product is defined through a universal construction that uses projections. We haven’t used any projections in our formulation of monoidal laws.

A bifunctor that behaves like a product without being a product is called a tensor product, often denoted by the infix operator ⊗. A definition of a tensor product in general is a bit tricky, but we won’t worry about it. We’ll just list its properties — the most important being associativity up to isomorphism.

Similarly, we don’t need the object t to be terminal. We never used its terminal property — namely, the existence of a unique morphism from any object to it. What we require is that it works well in concert with the tensor product. Which means that we want it to be the unit of the tensor product, again, up to isomorphism. Let’s put it all together:

A monoidal category is a category C equipped with a bifunctor called the tensor product:

⊗ :: C × C -> C

and a distinct object i called the unit object, together with three natural isomorphisms called, respectively, the associator and the left and right unitors:

αa b c :: (a ⊗ b) ⊗ c -> a ⊗ (b ⊗ c) λa :: i ⊗ a -> a ρa :: a ⊗ i -> a

(There is also a coherence condition for simplifying a quadruple tensor product.)

What’s important is that a tensor product describes many familiar bifunctors. In particular, it works for a product, a coproduct and, as we’ll see shortly, for the composition of endofunctors (and also for some more esoteric products like Day convolution). Monoidal categories will play an essential role in the formulation of enriched categories.

Monoid in a Monoidal Category

We are now ready to define a monoid in a more general setting of a monoidal category. We start by picking an object m. Using the tensor product we can form powers of m. The square of m is m ⊗ m. There are two ways of forming the cube of m, but they are isomorphic through the associator. Similarly for higher powers of m (that’s where we need the coherence conditions). To form a monoid we need to pick two morphisms:

μ :: m ⊗ m -> m η :: i -> m

where i is the unit object for our tensor product.

These morphisms have to satisfy associativity and unit laws, which can be expressed in terms of the following commuting diagrams:

Notice that it’s essential that the tensor product be a bifunctor because we need to lift pairs of morphisms to form products such as μ ⊗ id or η ⊗ id. These diagrams are just a straightforward generalization of our previous results for categorical products.

Monads as Monoids

Monoidal structures pop up in unexpected places. One such place is the functor category. If you squint a little, you might be able to see functor composition as a form of multiplication. The problem is that not any two functors can be composed — the target category of one has to be the source category of the other. That’s just the usual rule of composition of morphisms — and, as we know, functors are indeed morphisms in the category Cat. But just like endomorphisms (morphisms that loop back to the same object) are always composable, so are endofunctors. For any given category C, endofunctors from C to C form the functor category [C, C]. Its objects are endofunctors, and morphisms are natural transformations between them. We can take any two objects from this category, say endofunctors F and G, and produce a third object F ∘ G — an endofunctor that’s their composition.

Is endofunctor composition a good candidate for a tensor product? First, we have to establish that it’s a bifunctor. Can it be used to lift a pair of morphisms — here, natural transformations? The signature of the analog of bimap for the tensor product would look something like this:

bimap :: (a -> b) -> (c -> d) -> (a ⊗ c -> b ⊗ d)

If you replace objects by endofunctors, arrows by natural transformations, and tensor products by composition, you get:

(F -> F') -> (G -> G') -> (F ∘ G -> F' ∘ G')

which you may recognize as the special case of horizontal composition.

We also have at our disposal the identity endofunctor I, which can serve as the identity for endofunctor composition — our new tensor product. Moreover, functor composition is associative. In fact associativity and unit laws are strict — there’s no need for the associator or the two unitors. So endofunctors form a strict monoidal category with functor composition as tensor product.

What’s a monoid in this category? It’s an object — that is an endofunctor T; and two morphisms — that is natural transformations:

μ :: T ∘ T -> T η :: I -> T

Not only that, here are the monoid laws:

They are exactly the monad laws we’ve seen before. Now you understand the famous quote from Saunders Mac Lane:

All told, monad is just a monoid in the category of endofunctors.

You might have seen it emblazoned on some t-shirts at functional programming conferences.

Monads from Adjunctions

An adjunction, L ⊣ R, is a pair of functors going back and forth between two categories C and D. There are two ways of composing them giving rise to two endofunctors, R ∘ L and L ∘ R. As per an adjunction, these endofunctors are related to identity functors through two natural transformations called unit and counit:

η :: ID -> R ∘ L ε :: L ∘ R -> IC

Immediately we see that the unit of an adjunction looks just like the unit of a monad. It turns out that the endofunctor R ∘ L is indeed a monad. All we need is to define the appropriate μ to go with the η. That’s a natural transformation between the square of our endofunctor and the endofunctor itself or, in terms of the adjoint functors:

R ∘ L ∘ R ∘ L -> R ∘ L

And, indeed, we can use the counit to collapse the L ∘ R in the middle. The exact formula for μ is given by the horizontal composition:

μ = R ∘ ε ∘ L

Monadic laws follow from the identities satisfied by the unit and counit of the adjunction and the interchange law.

We don’t see a lot of monads derived from adjunctions in Haskell, because an adjunction usually involves two categories. However, the definitions of an exponential, or a function object, is an exception. Here are the two endofunctors that form this adjunction:

L z = z × s R b = s ⇒ b

You may recognize their composition as the familiar state monad:

R (L z) = s ⇒ (z × s)

We’ve seen this monad before in Haskell:

newtype State s a = State (s -> (a, s))

Let’s also translate the adjunction to Haskell. The left functor is the product functor:

newtype Prod s a = Prod (a, s)

and the right functor is the reader functor:

newtype Reader s a = Reader (s -> a)

They form the adjunction:

instance Adjunction (Prod s) (Reader s) where counit (Prod (Reader f, s)) = f s unit a = Reader (\s -> Prod (a, s))

You can easily convince yourself that the composition of the reader functor after the product functor is indeed equivalent to the state functor:

newtype State s a = State (s -> (a, s))

As expected, the unit of the adjunction is equivalent to the return function of the state monad. The counit acts by evaluating a function acting on its argument. This is recognizable as the uncurried version of the function runState:

runState :: State s a -> s -> (a, s) runState (State f) s = f s

(uncurried, because in counit it acts on a pair).

We can now define join for the state monad as a component of the natural transformation μ. For that we need a horizontal composition of three natural transformations:

μ = R ∘ ε ∘ L

In other words, we need to sneak the counit ε across one level of the reader functor. We can’t just call fmap directly, because the compiler would pick the one for the State functor, rather than the Reader functor. But recall that fmap for the reader functor is just left function composition. So we’ll use function composition directly.

We have to first peel off the data constructor State to expose the function inside the State functor. This is done using runState:

ssa :: State s (State s a) runState ssa :: s -> (State s a, s)

Then we left-compose it with the counit, which is defined by uncurry runState. Finally, we clothe it back in the State data constructor:

join :: State s (State s a) -> State s a join ssa = State (uncurry runState . runState ssa)

This is indeed the implementation of join for the State monad.

It turns out that not only every adjunction gives rise to a monad, but the converse is also true: every monad can be factorized into a composition of two adjoint functors. Such factorization is not unique though.

We’ll talk about the other endofunctor L ∘ R in the next section.

Next: Comonads.

December 27, 2016 at 6:53 pm

I assume by “Hask” you mean the category of cppo’s and continuous functions? If so, this has nothing much to do with Haskell, because it is not fully abstract with respect to the operational meaning of Haskell programs. It should be called CPPO, like everyone else does, and not the pretentious “Hask”, which serves only to mislead. In fact, Haskell has no semantics, which is pretty embarrassing for a supposedly mathematical language.

December 28, 2016 at 4:20 pm

The mapping a -> m b deserves a picture! I can see in my mind’s eye that you’ve taken the 3 node expression tree +(y (-1)) and spliced it over each of the three occurrences of x to obtain the new tree of type m b. All that’s missing is a color y to represent what happens to the pretty pink of x, and you’ve reached in and drawn the result of this monadic bind!

December 29, 2016 at 3:53 am

In the commuting diagram about unit laws in section “Monoid in a Monoidal Category”, the rightmost object should be the tensor product between m and i (not between m and id as it is shown).

December 29, 2016 at 11:18 am

@Juan Manuel: You’re right. I can’t even call it a “typo” since it’s hand-written. I’ll fix it at some point.

January 3, 2017 at 4:12 pm

I actually thought the “typo” was in having “id x m” rather than “id x mu”

January 3, 2017 at 6:00 pm

@jd823592: oops!

March 21, 2017 at 10:41 am

[…] 10. 2 Monoidal Categories (read text) […]

April 8, 2017 at 2:16 pm

Thank you for writing this series! It is by far the most intuitive and programmer friendly into to category theory out there.

I only wish I found it earlier. I very much hope you find energy and time to continue writing.

I have a question about the definition of mu/join natural transformation for R.L adjunction (mu = R . epsilon . L).

To me, a more straightforward definition is simply one that uses:

R (epsilon)

with epsilon viewed as a family of morphism and R fmaps them to act on D. This approach is actually what you have ended up using in your State monad example.

Interestingly, this approach does not use L. Is this somehow equivalent to the horizontal composition R . epsilon . L you are using in your definition?

April 9, 2017 at 1:31 pm

The L on the right is necessary to “shift” epsilon — to pick the right morphism from the family of morphisms. This is invisible in Haskell code because of type inference. The compiler figures out what component to pick by analyzing types. I tried to explain horizontal composition in more detail in this video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zkDVCQiveEo .

December 8, 2017 at 6:40 am

Shouldn’t the ‘equational law’

mu x (mu y z) = mu (mu x y) z

rather be:

mu (x, mu (y, z)) = mu (mu (x, y), z)

given that mu is defined as mu :: (m, m) -> m? This definition seems, at least, to be the one used going forward when using bimap to arrive at a point-free definition.

December 8, 2017 at 7:30 am

You’re right. I’m so used to currying, I overdid it.

December 16, 2017 at 1:18 pm

Hi Bartosz, thank you for this great article, after almost one year of struggling, finally I got to understand why “monad is a monoid in the category of endofunctors” 🙂

But I still have a small question, I can understand the version of monad laws based on Kleisli composition, I can also understand the version described as natural transformation, but I still find difficulty showing the equivalence relationship between them in rigorous math languages. Could you please elaborates slightly more on how “You can convince yourself that these laws guarantee that the composition of Kleisli arrows indeed satisfies the laws of a category”? Thanks!

December 17, 2017 at 4:38 am

The standard method of proof is to rewrite all natural transformations in terms of components (which are morphisms), keeping track of the objects.

August 9, 2018 at 8:00 am

Looks like in point-free version of unit laws bimap parameters should be swapped:

mu . bimap eta id = lambda

mu . bimap id eta = rho

August 9, 2018 at 12:59 pm

Fixed, thank you!

July 26, 2019 at 12:30 pm

Hello,

I am a programmer and want to understand monad using category theory. I learned each and every points from category theory which could leads me to monad. l am trying to understand monad and comonad using adjunction, but mu natural transformation is not underatood using adjunction. I can understand unit natural transformation I –> R•L using eta composing with other functions. But, I cannot get how R•L•R•L –> R•L emerges from adjunction. Same way I cannot get how L•R –> L•R•L•R emrges for comonad. I can understand that R•L –> I and I –> L•R are not welcome in adjunction then which compositions emerges R•L•R•L –> R•L?

Thanks

March 23, 2020 at 7:39 am

When you defined monad as monoid did u assume that every endofunctor has natural transformation mu? I thought not all endofunctor must not have a mu just like how not every endofunctor is monad.. but on the other hand, every endofunctor can be a monad (free monad) so do they all have a mu??

March 23, 2020 at 10:19 am

Not every endofunctor is a monad. What you can do is to take any endofunctor and build a free monad from it. But the free monad is not the same as the original endofunctor. It’s analogous to: not every type X is a monoid, but you can build a free monoid as a list of X.