Previously: (Weak) Factorization Systems.

It’s been known since Lambek that typed lambda calculus can be modeled in a cartesian closed category, CCC. Cartesian means that you can form products, and closed means that you can form function types. Loosely speaking, types are modeled as objects and functions as arrows.

More precisely, objects correspond to contexts— which are cartesian products of types, with the terminal object representing the empty context. Arrows correspond to terms in those contexts.

Mathematicians and computer scientist use special syntax to formalize type theory that is used in lambda calculus. For instance a typing judgment:

states that is a type. The turnstile symbol is used to separate contexts from judgments. Here, the context is empty (nothing on the left of the turnstile). Categorically, this means that

is an object.

A more general context is a product of objects

. The judgment:

tells us that the type may depend on other types

, in which case

is a type constructor. The canonical example of a type constructor is a list.

A term of type

in some context

is written as:

We interpret it as an arrow from the cartesian product of types that form to the object

:

Things get more interesting when we allow types to not only depend on other types, but also on values. This is the real power of dependent types à la Martin-Löf.

For instance, the judgment:

defines a single-argument type family. For every argument of type

it produces a new type

. The canonical example of a dependent type is a counted vector, which encodes length (a value of type

) in its type.

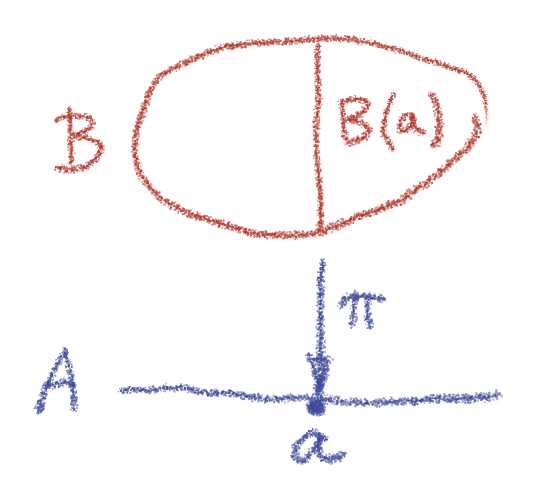

Categorically, we model a type family as a fibration given by an arrow . The type

is a fiber

.

In the case of counted vectors, the projection gives the length of the vector.

In general, a type family may depend on multiple arguments, as in:

Here, each type in the context may depend on the values defined by its predecessor. For instance, may depend on

,

may depend on

and

, and so on.

Categorically, we model such a judgment as a tower of fibrations:

Notice that the context is no longer a cartesian product of types but rather an ordered series of fibrations.

A term in a dependently typed system has to satisfy an additional condition: it has to map into the correct fiber. For instance, in the judgment:

not only depends on

, but so does the type

. If we model

as an arrow

, we have to make sure that

is projected back to

. Categorically, we call such maps sections:

In other words, a section is an arrow that is a right inverse of a projection, .

Thus a well-formed vector-valued term produces, for every , a vector of lenght

.

In general, a term:

is interpreted as a section of the projection

.

At this point one usually introduces the definitions of dependent sums and products, which requires the modeling category to be locally cartesian closed. We’ll instead concentrate on the identity types, which are closely related to homotopy theory.

Next: Identity Types.

Leave a comment