I have recently watched a talk by Gabriel Gonzalez about folds, which caught my attention because of my interest in both recursion schemes and optics. A Fold is an interesting abstraction. It encapsulates the idea of focusing on a monoidal contents of some data structure. Let me explain.

Suppose you have a data structure that contains, among other things, a bunch of values from some monoid. You might want to summarize the data by traversing the structure and accumulating the monoidal values in an accumulator. You may, for instance, concatenate strings, or add integers. Because we are dealing with a monoid, which is associative, we could even parallelize the accumulation.

In practice, however, data structures are rarely filled with monoidal values or, if they are, it’s not clear which monoid to use (e.g., in case of numbers, additive or multiplicative?). Usually monoidal values have to be extracted from the container. We need a way to convert the contents of the container to monoidal values, perform the accumulation, and then convert the result to some output type. This could be done, for instance by fist applying fmap, and then traversing the result to accumulate monoidal values. For performance reasons, we might prefer the two actions to be done in a single pass.

Here’s a data structure that combines two functions, one converting a to some monoidal value m and the other converting the final result to b. The traversal itself should not depend on what monoid is being used so, in Haskell, we use an existential type.

data Fold a b = forall m. Monoid m => Fold (a -> m) (m -> b)

The data constructor of Fold is polymorphic in m, so it can be instantiated for any monoid, but the client of Fold will have no idea what that monoid was. (In actual implementation, the client is secretly passed a table of functions: one to retrieve the unit of the monoid, and another to perform the mappend.)

The simplest container to traverse is a list and, indeed, we can use a Fold to fold a list. Here’s the less efficient, but easy to understand implementation

fold :: Fold a b -> [a] -> b fold (Fold s g) = g . mconcat . fmap s

See Gabriel’s blog post for a more efficient implementation.

A Fold is a functor

instance Functor (Fold a) where fmap f (Fold scatter gather) = Fold scatter (f . gather)

In fact it’s a Monoidal functor (in category theory, it’s called a lax monoidal functor)

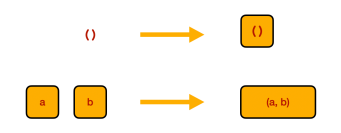

class Monoidal f where init :: f () combine :: f a -> f b -> f (a, b)

You can visualize a monoidal functor as a container with two additional properties: you can initialize it with a unit, and you can coalesce a pair of containers into a container of pairs.

instance Monoidal (Fold a) where -- Fold a () init = Fold bang id -- Fold a b -> Fold a c -> Fold a (b, c) combine (Fold s g) (Fold s' g') = Fold (tuple s s') (bimap g g')

where we used the following helper functions

bang :: a -> () bang _ = () tuple :: (c -> a) -> (c -> b) -> (c -> (a, b)) tuple f g = \c -> (f c, g c)

This property can be used to easily aggregate Folds.

In Haskell, a monoidal functor is equivalent to the more common applicative functor.

A list is the simplest example of a recursive data structure. The immediate question is, can we use Fold with other recursive data structures? The generalization of folding for recursively-defined data structures is called a catamorphism. What we need is a monoidal catamorphism.

Algebras and catamorphisms

Here’s a very short recap of simple recursion schemes (for more, see my blog). An algebra for a functor f with the carrier a is defined as

type Algebra f a = f a -> a

Think of the functor f as defining a node in a recursive data structure (often, this functor is defined as a sum type, so we have more than one type of node). An algebra extracts the contents of this node and summarizes it. The type a is called the carrier of the algebra.

A fixed point of a functor is the carrier of its initial algebra

newtype Fix f = Fix { unFix :: f (Fix f) }

Think of it as a node that contains other nodes, which contain nodes, and so on, recursively.

A catamorphism generalizes a fold

cata :: Functor f => Algebra f a -> Fix f -> a cata alg = alg . fmap (cata alg) . unFix

It’s a recursively defined function. It’s first applied using fmap to all the children of the node. Then the node is evaluated using the algebra.

Monoidal algebras

We would like to use a Fold to fold an arbitrary recursive data structure. We are interested in data structures that store values of type a which can be converted to monoidal values. Such structures are generated by functors of two arguments (bifunctors).

class Bifunctor f where bimap :: (a -> a') -> (b -> b') -> f a b -> f a' b'

In our case, the first argument will be the payload and the second, the placeholder for recursion and the carrier for the algebra.

We start by defining a monoidal algebra for such a functor by assuming that it has a monoidal payload, and that the child nodes have already been evaluated to a monoidal value

type MAlgebra f = forall m. Monoid m => f m m -> m

A monoidal algebra is polymorphic in the monoid m reflecting the requirement that the evaluation should only be allowed to use monoidal unit and monoidal multiplication.

A bifunctor is automatically a functor in its second argument

instance Bifunctor f => Functor (f a) where fmap g = bimap id g

We can apply the fixed point to this functor to define a recursive data structure Fix (f a).

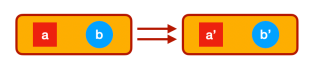

We can then use Fold to convert the payload of this data structure to monoidal values, and then apply a catamorphism to fold it

cat :: Bifunctor f => MAlgebra f -> Fold a b -> Fix (f a) -> b

cat malg (Fold s g) = g . cata alg

where

alg = malg . bimap s id

Here’s this process in more detail. This is the monoidal catamorphism that we are defining:

We first apply cat, recursively, to all the children. This replaces the children with monoidal values. We also convert the payload of the node to the same monoid using the first component of Fold. We can then use the monoidal algebra to combine the payload with the results of folding the children.

Finally, we convert the result to the target type.

We have factorized the original problem in three orthogonal directions: the monoidal algebra, the Fold, and the traversal of the particular recursive data structure.

Example

Here’s a simple example. We define a bifunctor that generates a binary tree with arbitrary payload a stored at the leaves

data TreeF a r = Leaf a | Node r r

It is indeed a bifunctor

instance Bifunctor TreeF where bimap f g (Leaf a) = Leaf (f a) bimap f g (Node r r') = Node (g r) (g r')

The recursive tree is generated as its fixed point

type Tree a = Fix (TreeF a)

We define two smart constructors to simplify the construction of trees

leaf :: a -> Tree a leaf a = Fix (Leaf a) node :: Tree a -> Tree a -> Tree a node t t' = Fix (Node t t')

We can define a monoidal algebra for this functor. Notice that it only uses monoidal operations (we don’t even need the monoidal unit here, since values are stored in the leaves). It will therefore work for any monoid

myAlg :: MAlgebra TreeF myAlg (Leaf m) = m myAlg (Node m m') = m <> m'

Separately, we define a Fold whose internal monoid is Sum Int. It converts Double values to this monoid using floor, and converts the result to a String using show

myFold :: Fold Double String

myFold = Fold floor' show'

where

floor' :: Double -> Sum Int

floor' = Sum . floor

show' :: Sum Int -> String

show' = show . getSum

This Fold has no knowledge of the data structure we’ll be traversing. It’s only interested in its payload.

Here’s a small tree containing three Doubles

myTree :: Tree Double myTree = node (node (leaf 2.3) (leaf 10.3)) (leaf 1.1)

We can monoidally fold this tree and display the resulting String

Notice that we can use the same monoidal catamorphism with any monoidal algebra and any Fold.

The following pragmas were used in this program

{-# language ExistentialQuantification #-}

{-# language RankNTypes #-}

{-# language FlexibleInstances #-}

{-# language IncoherentInstances #-}

Relation to Optics

A Fold can be seen as a form of optic. It takes a source type, extracts a monoidal value from it, and maps a monoidal value to the target type; all the while keeping the monoid existential. Existential types are represented in category theory as coends—here we are dealing with a coend over the category of monoids in some monoidal category

. There is an obvious forgetful functor

that forgets the monoidal structure and produces an object of

. Here’s the categorical formula that corresponds to

Fold

This coend is taken over a profunctor in the category of monoids

The coend is defined as a disjoint union of sets in which we identify some of the elements. Given a monoid homomorphism

, and a pair of morphisms

we identify the pairs

This is exactly what we need to make our monoidal catamorphism work. This condition ensures that the following two scenarios are equivalent:

- Use the function

to extract monoidal values, transform these values to another monoid using

, do the folding in the second monoid, and translate the result using

- Use the function

to extract monoidal values, do the folding in the first monoid, use

to transform the result to the second monoid, and translate the result using

Since the monoidal catamorphism only uses monoidal operations and is a monoid homomorphism, this condition is automatically satisfied.

June 16, 2020 at 2:29 am

Thank you for the info.

The code worked after I added:

import Prelude hiding (Functor,fmap)

import Data.Monoid

Now I play with it.

June 16, 2020 at 11:48 pm

I did a peer review of the article using SciHive: https://www.scihive.org/paper/88689?info=True

Hope this is helpful

August 1, 2020 at 9:36 am

[…] Monoidal catamorphisms. ~ Bartosz Milewski (@BartoszMilewski). #Haskell #CategoryTheory […]

August 22, 2020 at 1:37 am

[…] Перевод статьи Бартоша Милевски «Monoidal Catamorphisms» (исходный текст расположен по адресу — Текст оригинальной статьи). […]