This is part 30 of Categories for Programmers. Previously: Topoi. See the Table of Contents.

Nowadays you can’t talk about functional programming without mentioning monads. But there is an alternative universe in which, by chance, Eugenio Moggi turned his attention to Lawvere theories rather than monads. Let’s explore that universe.

Universal Algebra

There are many ways of describing algebras at various levels of abstraction. We try to find a general language to describe things like monoids, groups, or rings. At the simplest level, all these constructions define operations on elements of a set, plus some laws that must be satisfied by these operations. For instance, a monoid can be defined in terms of a binary operation that is associative. We also have a unit element and unit laws. But with a little bit of imagination we can turn the unit element to a nullary operation — an operation that takes no arguments and returns a special element of the set. If we want to talk about groups, we add a unary operator that takes an element and returns its inverse. There are corresponding left and right inverse laws to go with it. A ring defines two binary operators plus some more laws. And so on.

The big picture is that an algebra is defined by a set of n-ary operations for various values of n, and a set of equational identities. These identities are all universally quantified. The associativity equation must be satisfied for all possible combinations of three elements, and so on.

Incidentally, this eliminates fields from consideration, for the simple reason that zero (unit with respect to addition) has no inverse with respect to multiplication. The inverse law for a field can’t be universally quantified.

This definition of a universal algebra can be extended to categories other than Set, if we replace operations (functions) with morphisms. Instead of a set, we select an object a (called a generic object). A unary operation is just an endomorphism of a. But what about other arities (arity is the number of arguments for a given operation)? A binary operation (arity 2) can be defined as a morphism from the product a×a back to a. A general n-ary operation is a morphism from the n-th power of a to a:

αn :: an -> a

A nullary operation is a morphism from the terminal object (the zeroth power of a). So all we need in order to define any algebra is a category whose objects are powers of one special object a. The specific algebra is encoded in the hom-sets of this category. This is a Lawvere theory in a nutshell.

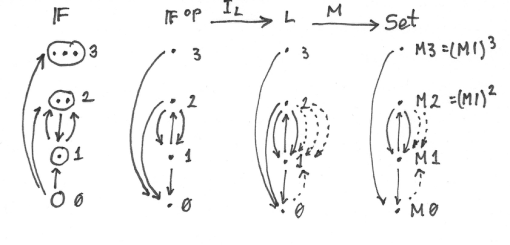

The derivation of Lawvere theories goes through many steps, so here’s the roadmap:

- Category of finite sets FinSet.

- Its skeleton F.

- Its opposite Fop.

- Lawvere theory L: an object in the category Law.

- Model

Mof a Lawvere category: an object in the categoryMod(Law, Set).

Lavwere Theories

All Lawvere theories share a common backbone. All objects in a Lawvere theory are generated from just one object using products (really, just powers). But how do we define these products in a general category? It turns out that we can define products using a mapping from a simpler category. In fact this simpler category may define coproducts instead of products, and we’ll use a contravariant functor to embed them in our target category. A contravariant functor turns coproducts into products and injections to projections.

The natural choice for the backbone of a Lawvere category is the category of finite sets, FinSet. It contains the empty set 0, a singleton set 1, a two-element set 2, and so on. All objects in this category can be generated from the singleton set using coproducts (treating the empty set as a special case of a nullary coproduct). For instance, a two-element set is a sum of two singletons, 2 = 1 + 1, as expressed in Haskell:

type Two = Either () ()

However, even though it’s natural to think that there’s only one empty set, there may be many distinct singleton sets. In particular, the set 1 + 0 is different from the set 0 + 1, and different from 1 — even though they are all isomorphic. The coproduct in the category of sets is not associative. We can remedy that situation by building a category that identifies all isomorphic sets. Such a category is called a skeleton. In other words, the backbone of any Lawvere theory is the skeleton F of FinSet. The objects in this category can be identified with natural numbers (including zero) that correspond to the element count in FinSet. Coproduct plays the role of addition. Morphisms in F correspond to functions between finite sets. For instance, there is a unique morphism from 0 to n (empty set being the initial object), no morphisms from n to 0 (except 0->0), n morphisms from 1 to n (the injections), one morphism from n to 1, and so on. Here, n denotes an object in F corresponding to all n-element sets in FinSet that have been identified through isomorphims.

Using the category F we can formally define a Lawvere theory as a category L equipped with a special functor

IL :: Fop -> L

This functor must be a bijection on objects and it must preserve finite products (products in Fop are the same as coproducts in F):

IL (m × n) = IL m × IL n

You may sometimes see this functor characterized as identity-on-objects, which means that the objects in F and L are the same. We will therefore use the same names for them — we’ll denote them by natural numbers. Keep in mind though that objects in F are not the same as sets (they are classes of isomorphic sets).

The hom-sets in L are, in general, richer than those in Fop. They may contain morphisms other than the ones corresponding to functions in FinSet (the latter are sometimes called basic product operations). Equational laws of a Lawvere theory are encoded in those morphisms.

The key observation is that the singleton set 1 in F is mapped to some object that we also call 1 in L, and all the other objects in L are automatically powers of this object. For instance, the two-element set 2 in F is the coproduct 1+1, so it must be mapped to a product 1×1 (or 12) in L. In this sense, the category F behaves like the logarithm of L.

Among morphisms in L we have those transferred by the functor IL from F. They play structural role in L. In particular coproduct injections ik become product projections pk. A useful intuition is to imagine the projection:

pk :: 1n -> 1

as the prototype for a function of n variables that ignores all but the k’th variable. Conversely, constant morphisms n->1 in F become diagonal morphisms 1->1n in L. They correspond to duplication of variables.

The interesting morphisms in L are the ones that define n-ary operations other than projections. It’s those morphisms that distinguish one Lawvere theory from another. These are the multiplications, the additions, the selections of unit elements, and so on, that define the algebra. But to make L a full category, we also need compound operations n->m (or, equivalently, 1n -> 1m). Because of the simple structure of the category, they turn out to be products of simpler morphisms of the type n->1. This is a generalization of the statement that a function that returns a product is a product of functions (or, as we’ve seen earlier, that the hom-functor is continuous).

Lawvere theory L is based on Fop, from which it inherits the “boring” morphisms that define the products. It adds the “interesting” morphisms that describe the n-ary operations (dotted arrows).

Lavwere theories form a category Law, in which morphisms are functors that preserve finite products and commute with the functors I. Given two such theories, (L, IL) and (L', I'L'), a morphism between them is a functor F :: L -> L' such that:

F (m × n) = F m × F n F ∘ IL = I'L'

Morphisms between Lawvere theories encapsulate the idea of the interpretation of one theory inside another. For instance, group multiplication may be interpreted as monoid multiplication if we ignore inverses.

The simplest trivial example of a Lawvere category is Fop itself (corresponding to the choice of the identity functor for IL). This Lawvere theory that has no operations or laws happens to be the initial object in Law.

At this point it would be very helpful to present a non-trivial example of a Lawvere theory, but it would be hard to explain it without first understanding what models are.

Models of Lawvere Theories

The key to understand Lawvere theories is to realize that one such theory generalizes a lot of individual algebras that share the same structure. For instance, the Lawvere theory of monoids describes the essence of being a monoid. It must be valid for all monoids. A particular monoid becomes a model of such a theory. A model is defined as a functor from the Lawvere theory L to the category of sets Set. (There are generalizations of Lawvere theories that use other categories for models but here I’ll just concentrate on Set.) Since the structure of L depends heavily on products, we require that such a functor preserve finite products. A model of L, also called the algebra over the Lawvere theory L, is therefore defined by a functor:

M :: L -> Set M (a × b) ≅ M a × M b

Notice that we require the preservation of products only up to isomorphism. This is very important, because strict preservation of products would eliminate most interesting theories.

The preservation of products by models means that the image of M in Set is a sequence of sets generated by powers of the set M 1 — the image of the object 1 from L. Let’s call this set a. (This set is sometimes called a sort, and such algebra is called single-sorted. There exist generalizations of Lawvere theories to multi-sorted algebras.) In particular, binary operations from L are mapped to functions:

a × a -> a

As with any functor, it’s possible that multiple morphisms in L are collapsed to the same function in Set.

Incidentally, the fact that all laws are universally quantified equalities means that every Lawvere theory has a trivial model: a constant functor mapping all objects to the singleton set, and all morphisms to the identity function on it.

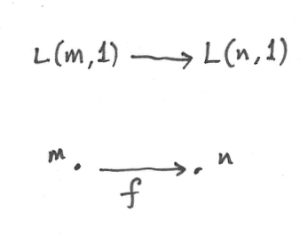

A general morphism in L of the form m -> n is mapped to a function:

am -> an

If we have two different models, M and N, a natural transformation between them is a family of functions indexed by n:

μn :: M n -> N n

or, equivalently:

μn :: an -> bn

where b = N 1.

Notice that the naturality condition guarantees the preservation of n-ary operations:

N f ∘ μn = μ1 ∘ M f

where f :: n -> 1 is an n-ary operation in L.

The functors that define models form a category of models, Mod(L, Set), with natural transformations as morphisms.

Consider a model for the trivial Lawvere category Fop. Such model is completely determined by its value at 1, M 1. Since M 1 can be any set, there are as many of these models as there are sets in Set. Moreover, every morphism in Mod(Fop, Set) (a natural transformation between functors M and N) is uniquely determined by its component at M 1. Conversely, every function M 1 -> N 1 induces a natural transformation between the two models M and N. Therefore Mod(Fop, Set) is equivalent to Set.

The Theory of Monoids

The simplest nontrivial example of a Lawvere theory describes the structure of monoids. It is a single theory that distills the structure of all possible monoids, in the sense that the models of this theory span the whole category Mon of monoids. We’ve already seen a universal construction, which showed that every monoid can be obtained from an appropriate free monoid by identifying a subset of morphisms. So a single free monoid already generalizes a whole lot of monoids. There are, however, infinitely many free monoids. The Lawvere theory for monoids LMon combines all of them in one elegant construction.

Every monoid must have a unit, so we have to have a special morphism η in LMon that goes from 0 to 1. Notice that there can be no corresponding morphism in F. Such morphism would go in the opposite direction, from 1 to 0 which, in FinSet, would be a function from the singleton set to the empty set. No such function exists.

Next, consider morphisms 2->1, members of LMon(2, 1), which must contain prototypes of all binary operations. When constructing models in Mod(LMon, Set), these morphisms will be mapped to functions from the cartesian product M 1 × M 1 to M 1. In other words, functions of two arguments.

The question is: how many functions of two arguments can one implement using only the monoidal operator. Let’s call the two arguments a and b. There is one function that ignores both arguments and returns the monoidal unit. Then there are two projections that return a and b, respectively. They are followed by functions that return ab, ba, aa, bb, aab, and so on… In fact there are as many such functions of two arguments as there are elements in the free monoid with generators a and b. Notice that LMon(2, 1) must contain all those morphisms because one of the models is the free monoid. In a free monoid they correspond to distinct functions. Other models may collapse multiple morphisms in LMon(2, 1) down to a single function, but not the free monoid.

If we denote the free monoid with n generators n*, we may identify the hom-set L(2, 1) with the hom-set Mon(1*, 2*) in Mon, the category of monoids. In general, we pick LMon(m, n) to be Mon(n*, m*). In other words, the category LMon is the opposite of the category of free monoids.

The category of models of the Lawvere theory for monoids, Mod(LMon, Set), is equivalent to the category of all monoids, Mon.

Lawvere Theories and Monads

As you may remember, algebraic theories can be described using monads — in particular algebras for monads. It should be no surprise then that there is a connection between Lawvere theories and monads.

First, let’s see how a Lawvere theory induces a monad. It does it through an adjunction between a forgetful functor and a free functor. The forgetful functor U assigns a set to each model. This set is given by evaluating the functor M from Mod(L, Set) at the object 1 in L.

Another way of deriving U is by exploiting the fact that Fop is the initial object in Law. It meanst that, for any Lawvere theory L, there is a unique functor Fop -> L. This functor induces the opposite functor on models (since models are functors from theories to sets):

Mod(L, Set) -> Mod(Fop, Set)

But, as we discussed, the category of models of Fop is equivalent to Set, so we get the forgetful functor:

U :: Mod(L, Set) -> Set

It can be shown that so defined U always has a left adjoint, the free functor F.

This is easily seen for finite sets. The free functor F produces free algebras. A free algebra is a particular model in Mod(L, Set) that is generated from a finite set of generators n. We can implement F as the representable functor:

L(n, -) :: L -> Set

To show that it’s indeed free, all we have to do is to prove that it’s a left adjoint to the forgetful functor:

Mod(L(n, -), M) ≅ Set(n, U(M))

Let’s simplify the right hand side:

Set(n, U(M)) ≅ Set(n, M 1) ≅ (M 1)n ≅ M n

(I used the fact that a set of morphisms is isomorphic to the exponential which, in this case, is just the iterated product.) The adjunction is the result of the Yoneda lemma:

[L, Set](L(n, -), M) ≅ M n

Together, the forgetful and the free functor define a monad T = U∘F on Set. Thus every Lawvere theory generates a monad.

It turns out that the category of algebras for this monad is equivalent to the category of models.

You may recall that monad algebras define ways to evaluate expressions that are formed using monads. A Lawvere theory defines n-ary operations that can be used to generate expressions. Models provide means to evaluate these expressions.

The connection between monads and Lawvere theories doesn’t go both ways, though. Only finitary monads lead to Lawvere thories. A finitary monad is based on a finitary functor. A finitary functor on Set is fully determined by its action on finite sets. Its action on an arbitrary set a can be evaluated using the following coend:

F a = ∫ n an × (F n)

Since the coend generalizes a coproduct, or a sum, this formula is a generalization of a power series expansion. Or we can use the intuition that a functor is a generalized container. In that case a finitary container of as can be described as a sum of shapes and contents. Here, F n is a set of shapes for storing n elements, and the contents is an n-tuple of elements, itself an element of an. For instance, a list (as a functor) is finitary, with one shape for every arity. A tree has more shapes per arity, and so on.

First off, all monads that are generated from Lawvere theories are finitary and they can be expressed as coends:

TL a = ∫ n an × L(n, 1)

Conversely, given any finitary monad T on Set, we can construct a Lawvere theory. We start by constructing a Kleisli category for T. As you may remember, a morphism in a Kleisli category from a to b is given by a morphism in the underlying category:

a -> T b

When restricted to finite sets, this becomes:

m -> T n

The category opposite to this Kleisli category, KlTop, restricted to finite sets, is the Lawvere theory in question. In particular, the hom-set L(n, 1) that describes n-ary operations in L is given by the hom-set KlT(1, n).

It turns out that most monads that we encounter in programming are finitary, with the notable exception of the continuation monad. It is possible to to extend the notion of Lawvere theory beyond finitary operations.

Monads as Coends

Let’s explore the coend formula in more detail.

TL a = ∫ n an × L(n, 1)

To begin with, this coend is taken over a profunctor P in F defined as:

P n m = an × L(m, 1)

This profunctor is contravariant in the first argument, n. Consider how it lifts morphisms. A morphism in FinSet is a mapping of finite sets f :: m -> n. Such a mapping describes a selection of m elements from an n-element set (repetitions are allowed). It can be lifted to the mapping of powers of a, namely (notice the direction):

an -> am

The lifting simply selects m elements from a tuple of n elements (a1, a2,...an) (possibly with repetitions).

For instance, let’s take fk :: 1 -> n — a selection of the kth element from an n-element set. It lifts to a function that takes a n-tuple of elements of a and returns the kth one.

Or let’s take f :: m -> 1 — a constant function that maps all m elements to one. Its lifting is a function that takes a single element of a and duplicates it m times:

λx -> (x, x, ... x)

You might notice that it’s not immediately obvious that the profunctor in question is covariant in the second argument. The hom-functor L(m, 1) is actually contravariant in m. However, we are taking the coend not in the category L but in the category F. The coend variable n goes over finite sets (or the skeletons of such). The category L contains the opposite of F, so a morphism m -> n in F is a member of L(n, m) in L (the embedding is given by the functor IL).

Let’s check the functoriality of L(m, 1) as a functor from F to Set. We want to lift a function f :: m -> n, so our goal is to implement a function from L(m, 1) to L(n, 1). Corresponding to the function f there is a morphism in L from n to m (notice the direction). Precomposing this morphism with L(m, 1) gives us a subset of L(n, 1).

Notice that, by lifting a function 1->n we can go from L(1, 1) to L(n, 1). We’ll use this fact later on.

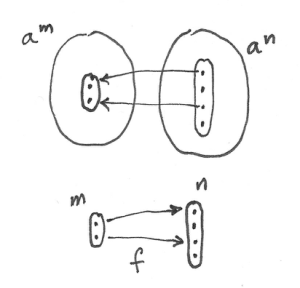

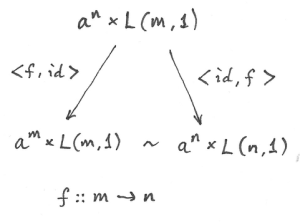

The product of a contravariant functor an and a covariant functor L(m, 1) is a profunctor Fop×F->Set. Remember that a coend can be defined as a coproduct (disjoint sum) of all the diagonal members of a profunctor, in which some elements are identified. The identifications correspond to cowedge conditions.

Here, the coend starts as the disjoint sum of sets an × L(n, 1) over all ns. The identifications can be generated by expressing the coend as a coequilizer. We start with an off-diagonal term an × L(m, 1). To get to the diagonal, we can apply a morphism f :: m -> n either to the first or the second component of the product. The two results are then identified.

I have shown before that the lifting of f :: 1 -> n results in these two transformations:

an -> a

and:

L(1, 1) -> L(n, 1)

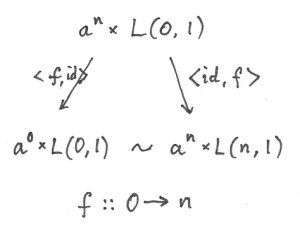

Therefore, starting from an × L(1, 1) we can reach both:

a × L(1, 1)

when we lift <f, id> and:

an × L(n, 1)

when we lift <id, f>. This doesn’t mean, however, that all elements of an × L(n, 1) can be identified with a × L(1, 1). That’s because not all elements of L(n, 1) can be reached from L(1, 1). Remember that we can only lift morphisms from F. A non-trivial n-ary operation in L cannot be constructed by lifting a morphism f :: 1 -> n.

In other words, we can only identify all addends in the coend formula for which L(n, 1) can be reached from L(1, 1) through the application of basic morphisms. They are all equivalent to a × L(1, 1). Basic morphisms are the ones that are images of morphisms in F.

Let’s see how this works in the simplest case of the Lawvere theory, the Fop itself. In such a theory, every L(n, 1) can be reached from L(1, 1). This is because L(1, 1) is a singleton containing just the identity morphism, and L(n, 1) only contains morphisms corresponding to injections 1->n in F, which are basic morphisms. Therefore all the addends in the coproduct are equivalent and we get:

T a = a × L(1, 1) = a

which is the identity monad.

Lawvere Theory of Side Effects

Since there is such a strong connection between monads and Lawvere theories, it’s natural to ask the question if Lawvere theories could be used in programming as an alternative to monads. The major problem with monads is that they don’t compose nicely. There is no generic recipe for building monad transformers. Lawvere theories have an advantage in this area: they can be composed using coproducts and tensor products. On the other hand, only finitary monads can be easily converted to Lawvere theories. The outlier here is the continuation monad. There is ongoing research in this area (see bibliography).

To give you a taste of how a Lawvere theory can be used to describe side effects, I’ll discuss the simple case of exceptions that are traditionally implemented using the Maybe monad.

The Maybe monad is generated by the Lawvere theory with a single nullary operation 0->1. A model of this theory is a functor that maps 1 to some set a, and maps the nullary operation to a function:

raise :: () -> a

We can recover the Maybe monad using the coend formula. Let’s consider what the addition of the nullary operation does to the hom-sets L(n, 1). Besides creating a new L(0, 1) (which is absent from Fop), it also adds new morphisms to L(n, 1). These are the results of composing morphism of the type n->0 with our 0->1. Such contributions are all identified with a0 × L(0, 1) in the coend formula, because they can be obtained from:

an × L(0, 1)

by lifting 0->n in two different ways.

The coend reduces to:

TL a = a0 + a1

or, using Haskell notation:

type Maybe a = Either () a

which is equivalent to:

data Maybe a = Nothing | Just a

Notice that this Lawvere theory only supports the raising of exceptions, not their handling.

Next: Monads, Monoids, and Categories.

Challenges

- Enumarate all morphisms between 2 and 3 in F (the skeleton of FinSet).

- Show that the category of models for the Lawvere theory of monoids is equivalent to the category of monad algebras for the list monad.

- The Lawvere theory of monoids generates the list monad. Show that its binary operations can be generated using the corresponding Kleisli arrows.

- FinSet is a subcategory of Set and there is a functor that embeds it in Set. Any functor on Set can be restricted to FinSet. Show that a finitary functor is the left Kan extension of its own restriction.

Acknowledgments

I’m grateful to Gershom Bazerman for many useful comments.

Further Reading

- Functorial Semantics of Algebraic Theories, F. William Lawvere

- Notions of computation determine monads, Gordon Plotkin and John Power

August 26, 2017 at 9:17 pm

Is this the last chapter? Thanks

August 26, 2017 at 10:01 pm

I don’t know. I have covered more or less the whole of Mac Lane’s book plus elements of enriched categories and Lawvere theories. I could stop here, but I’m open to suggestions.

August 28, 2017 at 12:30 am

You linked TheCatsters’s videos in your blogs. They also talk about span, 2 category and metric spaces, etc. Those topics are interesting, but they did it too quickly and very hard for programmers like me to catch up. Would you like to talk about them? Thanks.

August 28, 2017 at 4:43 pm

Yes, I could explain the connection between bicategories, spans, monads, and monoids. I have covered metric spaces in enriched categories.

August 30, 2017 at 3:40 pm

Time to make epub

August 31, 2017 at 1:10 pm

Maybe a bit on n-categories?

September 1, 2017 at 6:11 am

Is this series available in any form besides the HTML? I agree with others requesting EPUB or PDF; this would make it easier to consume for a lot of people. Leanpub or something like a sphinx project in github would be great.

Even if you don’t have time for it, would you be opposed to someone else doing a conversion?

September 1, 2017 at 7:33 pm

Would you publish this as a book? 😉

September 3, 2017 at 10:13 am

I keep getting asked this question. I guess if there is a publisher who is willing to work on it with me, I could be convinced. It’s a lot of work though.

September 3, 2017 at 10:14 am

I am totally fine with somebody else doing the conversion.

September 3, 2017 at 11:43 am

Hi guys.

I prepare epub file with all parts. Should be ready at the end of month.

September 3, 2017 at 11:45 am

@Bartosz, @Austin, it will be ready at the end of this month 😀

September 3, 2017 at 11:48 am

OK, I’ve taken a swing at pulling some of your posts into a sphinx project: https://github.com/abingham/categories-for-programmers. It’s a pretty crude conversion, but the output EPUB seems to be entirely usable.

September 3, 2017 at 10:54 pm

@koziolekweb Will subsets be available as you work, or will it be a big-bang delivery?

I don’t know what tools you’re using to make the book, but feel free to build on what I put together if you want. It seems to work well, and I was able to convert chapter at about 10 minutes each. It’s a rough conversion, but I think the results were pretty solid.

September 4, 2017 at 11:31 am

@Ausitn, I work on well formatted, well look and reader friendly epub (light), but need some time for it 🙂

It is available here → https://github.com/Koziolek/category-theory-bm

At this moment I have ready preface && ch01. Today I should commit ch02

September 4, 2017 at 10:53 pm

Excellent, I’m looking forward to it!

September 5, 2017 at 7:32 am

In the meantime, I wanted to read those post in print so i’ve scraped the articles into a print friendly markdown (and rendered pdf) document available here. https://gist.github.com/IGI-111/d80a8a9356ec10e5027d1efe28190352

September 6, 2017 at 8:58 am

I too gave it a try. I manually converted the posts into clean HTML and used pandoc to produce an ePUB. The stylesheet needs some polishing but I’m quite happy with the result. https://github.com/rnhmjoj/category-theory-for-programmers

September 6, 2017 at 8:46 pm

@rnhmjoj would you like to provide the final epub file? Thanks

September 8, 2017 at 12:08 am

The sphinx build I put together is largely complete: https://github.com/abingham/categories-for-programmers. I’ve written a number of books, and in my experience something like this will be easier to work with than straight HTML/epub if you want to do any substantial edits. Plus I wanted to see the conversion process through to the end just to find all of the rough edges. The latest epub output is included in the repo, or you can build it yourself.

September 10, 2017 at 7:19 pm

@dhui_algebra: It’s in the release section: https://github.com/rnhmjoj/category-theory-for-programmers/releases

I have also added a PDF version.

September 16, 2017 at 5:42 am

@rnhmjoj Thanks a lot

November 13, 2017 at 10:14 pm

Thanks for writing this great series. I may have noticed one small mistake in this article:

“Incidentally, the fact that all laws are universally quantified equalities means that every Lawvere theory has a trivial model: a constant functor mapping all objects to a single set, and all morphisms to the identity function on it.”

Since models must preserve products, it seems to me that we can’t pick any set. Instead, we have to pick a set that is isomorphic to its own square (e.g. a singleton set).

November 14, 2017 at 3:01 am

You’re right, fixed!

November 16, 2017 at 10:15 am

Is there some way to throw some money at you. I love your work and would like to support you some.

November 16, 2017 at 3:14 pm

I appreciate the intention, but money is not an issue. But if there are more people with good intentions, maybe we could find a worthy cause in which to invest. For instance a fund to sponsor students’ participation in ICFP? Any volunteers to administer a foundation?

March 3, 2020 at 10:51 am

Section about The Theory of Monoids

“The question is: how many functions of two arguments can one implement

using only the monoidal operator. Let’s call the two arguments

a and b. There is one function that ignores both arguments and returns

the monoidal unit. Then there are two projections that return a and b,

respectively. They are followed by functions that return ab, ba, aa, bb,

aab, and so on… In fact there are as many such functions of two arguments

as there are elements in the free monoid with generators a and

b.”

I don’t quite understand this text above.

IMO, the number of these functions depends on two things:

The first thing is carry type m, since the total number of these functions is num-m^(num-m*num-m), in which num-m is the number of elements in m.

The second thing is monoid law, pick those specific functions that satisfy monoid law in m x m -> m.

But in category L_Mon, we can’t see elements in a object, how can we know how many functions of two arguments can one implement using only the monoidal operator ?

“Notice that L_Mon(2, 1) must contain all those morphisms because one

of the models is the free monoid. In a free monoid they correspond to

distinct functions.”

If we have a free monoid, for example [Bool], [Bool] is a free monoid with the monoidal operator list concatenation f.

f :: [Bool] x [Bool] -> [Bool]

f a b = a ++ b

There is only one function f, I dont see any other distinct functions.

Maybe I miss some keything…

Can you explain more about these two text above?

Very thanks.

March 3, 2020 at 11:59 am

What about the function f a b = a ++b ++ a ?

March 3, 2020 at 7:27 pm

But this f is not a monoid operation.

The f use monoidal operator (++), but itself is not a monoid operation, for example:

f [True] [] = [True, True]

It does not satisfy the unit law of monoid. [True, True] != [True]

You said that

“A particular monoid becomes a model of such a theory. A model is defined as a functor from the Lawvere theory L to the category of sets Set.”

What makes me confused is:

Under some model (i.e. a functor M : L_Mon -> Set), what is the meaning of the image of M on morphisms?

For example:

Suppose I have two categories L_Mon and Set, now I want to construct a functor M : L_Mon -> Set to describe a particular free monoid [Bool].

The functor M must map objects in L_Mon to objects in Set:

0 -> ()

1 -> [Bool]

2 -> [Bool]x[Bool]

3 -> [Bool]x[Bool]x[Bool]

…

But how to map morphisms? More specifically, how to map morphisms from L_Mon(2,1) to Set([Bool]x[Bool],[Bool])?

It should map two projection morphisms in L_Mon(2,1) to two projection function in Set([Bool]x[Bool],[Bool]). But besides two projection morphisms in L_Mon(2,1), there are other infinite morphisms in L_Mon(2,1).

Does these “other infinite morphisms” collapse to one monoid evaluator (++) in Set([Bool]x[Bool],[Bool])? Or these “other infinite morphisms” are mapped to different functions in Set([Bool]x[Bool],[Bool])?

If M map “other infinite morphisms” to different functions in Set([Bool]x[Bool],[Bool]), what’s the meaning of these functions? Note that there is only one binary function (++) in Set([Bool]x[Bool] is legal, because [Bool] must be a monoid.

Very thanks.

March 4, 2020 at 1:05 pm

Every Lavwere theory has projections and diagonal mappings, e.g., delta x = (x, x). Compositions of diagonals and multiplication will produce all kinds of function of two variables, for example something like f a b = a * a * b, not just a * b.

We need these functions because most algebras have additional laws. For instance, you can have a law that says x * x * y = x * y. It’s an equality between two functions of two variables. It would be encoded in the corresponding Lawvere category, so each model would satisfy it.

March 8, 2020 at 10:30 am

Sorry for reply you later, because I need time to understand.

“We need these functions because most algebras have additional laws. For instance, you can have a law that says x * x * y = x * y.”

Yes, this is the reason why we need all these morphisms in a lawvere theory.

But what I want to know is why we need these morphisms in the image of the model? What are the meaning of these functions?

Still using the example above, under the image of the model M, we can find (++) in the Set([Bool]x[Bool],[Bool]), but we still have other functions (e.g. f a b = a * a * b). What does other functions play role?

It seems that the model does not automatically pick evaluator (e.g. μ, η) for us, right? Although, in the monoid example, it can pick (mempty) for use. Note that there are a lot of functions from () to [Bool], but under the image of M, there is only one function, because there is unique morphisms from 0 to 1 in L_Mon.

So M can pick (mempty) just a coincidence? In other algebras (e.g. ring, there is two special element, 0 and 1), model may not have that good luck.

March 9, 2020 at 4:13 pm

Remember that a functor must preserve all compositions. That’s a very strong requirement.

March 16, 2020 at 1:34 am

I have a question about FinSet: Is the FinSet you defined in this chapter the same as the FinSet on wikipedia?

In this Chapter, you mentioned that

“… FinSet. It contains the empty set 0, a singleton set 1, a two-element set 2, and so on. All objects in this category can be generated from the singleton set using coproducts (treating the empty set as a special case of a nullary coproduct). ”

In wikipedia (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/FinSet),

“FinSet is the category whose objects are all finite sets and whose morphisms are all functions between them.”

So in these two FinSet definitions, the objects are the same, but what about morphisms?

For example, in the wikipedia definition, there should be 8 (i.e. 2^3) morphisms in FinSet(3,2), but in the picture of Section 30.1, you did not draw these morphisms in F. (In fact, you did not draw FinSet, but in the skeleton F, there is no morphism from 3 to 2 in the picture)

I think these two definitions should be the same, but I just want to confirm it to convince yourself. Thank you.

March 19, 2020 at 12:36 pm

Yes, these are the same definitions. I haven’t drawn all the morphisms because there are two many of them (also, I haven’t drawn all the objects).

March 24, 2020 at 1:29 pm

Very sorry to bother you again, I have new question about the section: Lawvere Theory of Side Effects.

The question is: How does the coend reduce to T_L a = a^0 + a^1 ?

The picture of wedge condition you provided in this section only show the situation when m = 0 (e.g. start from p n 0), but m can be any object in L.

In my understanding, T_L a should be obtained by the quotient (exist n. a^n×L(n,1))/~ , where the equivalence relation ~ is generated by <f,id>(x,f)=<id,f>(x,f), for ∀(x,f)∈(exist n m. (a^n×L(m,1), m->n)), right?

In the picture you provided, all the elements in a^0×L(0,1) will be identified with corresponding elements a^n×L(n,1), but there are still some elements in a^n×L(n,1) are not identified.

For example, when n=2, there is only one element ((), 0->1) in a^0×L(0,1), this element will be identified with corresponding elements in a^2×L(2,1), they are ((a1,a2), 2->1), ((a3,a4), 2->1), … where 2->1 is the new morphism generated by (0->1)∘(2->0), where 2->0 is the basic morphism in F^op. There are still some other elements in a^2×L(2,1), e.g. ((a1,a2), fst), ((a3,a4), snd), … are not identified,right?

But I still do not understand exactly how you reduced the coend to a^0 + a^1. Could you explain further ?

Very thanks.

March 24, 2020 at 1:53 pm

Sorry, there is a typo in my comments above:

It should be generated by <f,id>(x,f) ~ <id,f>(x,f), where ~ means make them equivalence.

March 25, 2020 at 2:43 pm

The reasoning is that, when you only consider basic morphisms, you get T_a = a. Here we are adding one more morphism 0->1 together with its compositions with basic morphisms. The former indeed contributes a^0 to the coend, but the latter are all identified with it.

March 27, 2020 at 2:11 am

I seem to understand a little bit what you said. Let me explain my understanding:

Every L(n,1) except L(0,1) has two parts:

1st part is the new morphism caused by 0->1.

2nd part is basic morphisms in L(n,1).

1st part contributes a^0, which corresponds to the picture in the section “Lawvere Theory of Side Effects”.

2nd part contributes a^1, which corresponds to the last example of the section “Monads as Coends”

Is that right?

March 27, 2020 at 8:54 am

Correct.

August 30, 2020 at 7:36 pm

In order to construct Lawvere theories, we need all the objects in FinSet to be coproducts of 1 (or coproducts of coproducts, etc). So that requires there to be a bunch of arrows between objects. But do we need all the arrows? For example, would something go wrong in the construction of a Lawvere theory if there were no arrows from the bigger sets to the smaller sets?

August 30, 2020 at 9:35 pm

Coproducts in FinSet turn into products in a Lawvere theory. You want to have all products, because you’re modeling algebras.