This is part 14 of Categories for Programmers. Previously: Free Monoids. See the Table of Contents.

It’s about time we had a little talk about sets. Mathematicians have a love/hate relationship with set theory. It’s the assembly language of mathematics — at least it used to be. Category theory tries to step away from set theory, to some extent. For instance, it’s a known fact that the set of all sets doesn’t exist, but the category of all sets, Set, does. So that’s good. On the other hand, we assume that morphisms between any two objects in a category form a set. We even called it a hom-set. To be fair, there is a branch of category theory where morphisms don’t form sets. Instead they are objects in another category. Those categories that use hom-objects rather than hom-sets, are called enriched categories. In what follows, though, we’ll stick to categories with good old-fashioned hom-sets.

A set is the closest thing to a featureless blob you can get outside of categorical objects. A set has elements, but you can’t say much about these elements. If you have a finite set, you can count the elements. You can kind of count the elements of an inifinite set using cardinal numbers. The set of natural numbers, for instance, is smaller than the set of real numbers, even though both are infinite. But, maybe surprisingly, a set of rational numbers is the same size as the set of natural numbers.

Other than that, all the information about sets can be encoded in functions between them — especially the invertible ones called isomorphisms. For all intents and purposes isomorphic sets are identical. Before I summon the wrath of foundational mathematicians, let me explain that the distinction between equality and isomorphism is of fundamental importance. In fact it is one of the main concerns of the latest branch of mathematics, the Homotopy Type Theory (HoTT). I’m mentioning HoTT because it’s a pure mathematical theory that takes inspiration from computation, and one of its main proponents, Vladimir Voevodsky, had a major epiphany while studying the Coq theorem prover. The interaction between mathematics and programming goes both ways.

The important lesson about sets is that it’s okay to compare sets of unlike elements. For instance, we can say that a given set of natural transformations is isomorphic to some set of morphisms, because a set is just a set. Isomorphism in this case just means that for every natural transformation from one set there is a unique morphism from the other set and vice versa. They can be paired against each other. You can’t compare apples with oranges, if they are objects from different categories, but you can compare sets of apples against sets of oranges. Often transforming a categorical problem into a set-theoretical problem gives us the necessary insight or even lets us prove valuable theorems.

The Hom Functor

Every category comes equipped with a canonical family of mappings to Set. Those mappings are in fact functors, so they preserve the structure of the category. Let’s build one such mapping.

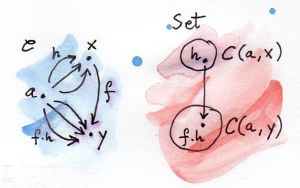

Let’s fix one object a in C and pick another object x also in C. The hom-set C(a, x) is a set, an object in Set. When we vary x, keeping a fixed, C(a, x) will also vary in Set. Thus we have a mapping from x to Set.

If we want to stress the fact that we are considering the hom-set as a mapping in its second argument, we use the notation:

C(a, -)

with the dash serving as the placeholder for the argument.

This mapping of objects is easily extended to the mapping of morphisms. Let’s take a morphism f in C between two arbitrary objects x and y. The object x is mapped to the set C(a, x), and the object y is mapped to C(a, y), under the mapping we have just defined. If this mapping is to be a functor, f must be mapped to a function between the two sets:

C(a, x) -> C(a, y)

Let’s define this function point-wise, that is for each argument separately. For the argument we should pick an arbitrary element of C(a, x) — let’s call it h. Morphisms are composable, if they match end to end. It so happens that the target of h matches the source of f, so their composition:

f ∘ h :: a -> y

is a morphism going from a to y. It is therefore a member of C(a, y).

We have just found our function from C(a, x) to C(a, y), which can serve as the image of f. If there is no danger of confusion, we’ll write this lifted function as:

C(a, f)

and its action on a morphism h as:

C(a, f) h = f ∘ h

Since this construction works in any category, it must also work in the category of Haskell types. In Haskell, the hom-functor is better known as the Reader functor:

type Reader a x = a -> x

instance Functor (Reader a) where

fmap f h = f . h

Now let’s consider what happens if, instead of fixing the source of the hom-set, we fix the target. In other words, we’re asking the question if the mapping

C(-, a)

is also a functor. It is, but instead of being covariant, it’s contravariant. That’s because the same kind of matching of morphisms end to end results in postcomposition by f; rather than precomposition, as was the case with C(a, -).

We have already seen this contravariant functor in Haskell. We called it Op:

type Op a x = x -> a

instance Contravariant (Op a) where

contramap f h = h . f

Finally, if we let both objects vary, we get a profunctor C(-, =), which is contravariant in the first argument and covariant in the second (to underline the fact that the two arguments may vary independently, we use a double dash as the second placeholder). We have seen this profunctor before, when we talked about functoriality:

instance Profunctor (->) where dimap ab cd bc = cd . bc . ab lmap = flip (.) rmap = (.)

The important lesson is that this observation holds in any category: the mapping of objects to hom-sets is functorial. Since contravariance is equivalent to a mapping from the opposite category, we can state this fact succintly as:

C(-, =) :: Cop × C -> Set

Representable Functors

We’ve seen that, for every choice of an object a in C, we get a functor from C to Set. This kind of structure-preserving mapping to Set is often called a representation. We are representing objects and morphisms of C as sets and functions in Set.

The functor C(a, -) itself is sometimes called representable. More generally, any functor F that is naturally isomorphic to the hom-functor, for some choice of a, is called representable. Such functor must necessarily be Set-valued, since C(a, -) is.

I said before that we often think of isomorphic sets as identical. More generally, we think of isomorphic objects in a category as identical. That’s because objects have no structure other than their relation to other objects (and themselves) through morphisms.

For instance, we’ve previously talked about the category of monoids, Mon, that was initially modeled with sets. But we were careful to pick as morphisms only those functions that preserved the monoidal structure of those sets. So if two objects in Mon are isomorphic, meaning there is an invertible morphism between them, they have exactly the same structure. If we peeked at the sets and functions that they were based upon, we’d see that the unit element of one monoid was mapped to the unit element of another, and that a product of two elements was mapped to the product of their mappings.

The same reasoning can be applied to functors. Functors between two categories form a category in which natural transformations play the role of morphisms. So two functors are isomorphic, and can be thought of as identical, if there is an invertible natural transformation between them.

Let’s analyze the definition of the representable functor from this perspective. For F to be representable we require that: There be an object a in C; one natural transformation α from C(a, -) to F; another natural transformation, β, in the opposite direction; and that their composition be the identity natural transformation.

Let’s look at the component of α at some object x. It’s a function in Set:

αx :: C(a, x) -> F x

The naturality condition for this transformation tells us that, for any morphism f from x to y, the following diagram commutes:

F f ∘ αx = αy ∘ C(a, f)

In Haskell, we would replace natural transformations with polymorphic functions:

alpha :: forall x. (a -> x) -> F x

with the optional forall quantifier. The naturality condition

fmap f . alpha = alpha . fmap f

is automatically satisfied due to parametricity (it’s one of those theorems for free I mentioned earlier), with the understanding that fmap on the left is defined by the functor F, whereas the one on the right is defined by the reader functor. Since fmap for reader is just function precomposition, we can be even more explicit. Acting on h, an element of C(a, x), the naturality condition simplifies to:

fmap f (alpha h) = alpha (f . h)

The other transformation, beta, goes the opposite way:

beta :: forall x. F x -> (a -> x)

It must respect naturality conditions, and it must be the inverse of α:

α ∘ β = id = β ∘ α

We will see later that a natural transformation from C(a, -) to any Set-valued functor always exists, as long as F a is non-empty (Yoneda’s lemma) but it’s not necessarily invertible.

Let me give you an example in Haskell with the list functor and Int as a. Here’s a natural transformation that does the job:

alpha :: forall x. (Int -> x) -> [x] alpha h = map h [12]

I have arbitrarily picked the number 12 and created a singleton list with it. I can then fmap the function h over this list and get a list of the type returned by h. (There are actually as many such transformations as there are list of integers.)

The naturality condition is equivalent to the composability of map (the list version of fmap):

map f (map h [12]) = map (f . h) [12]

But if we tried to find the inverse transformation, we would have to go from a list of arbitrary type x to a function returning x:

beta :: forall x. [x] -> (Int -> x)

You might think of retrieving an x from the list, e.g., using head, but that won’t work for an empty list. Notice that there is no choice for the type a (in place of Int) that would work here. So the list functor is not representable.

Remember when we talked about Haskell (endo-) functors being a little like containers? In the same vein we can think of representable functors as containers for storing memoized results of function calls (the members of hom-sets in Haskell are just functions). The representing object, the type a in C(a, -), is thought of as the key type, with which we can access the tabulated values of a function. The transformation we called α is called tabulate, and its inverse, β, is called index. Here’s a (slightly simplified) Representable class definition:

class Representable f where type Rep f :: * tabulate :: (Rep f -> x) -> f x index :: f x -> Rep f -> x

Notice that the representing type, our a, which is called Rep f here, is part of the definition of Representable. The star just means that Rep f is a type (as opposed to a type constructor, or other more exotic kinds).

Infinite lists, or streams, which cannot be empty, are representable.

data Stream x = Cons x (Stream x)

You can think of them as memoized values of a function taking an Integer as an argument. (Strictly speaking, I should be using non-negative natural numbers, but I didn’t want to complicate the code.)

To tabulate such a function, you create an infinite stream of values. Of course, this is only possible because Haskell is lazy. The values are evaluated on demand. You access the memoized values using index:

instance Representable Stream where

type Rep Stream = Integer

tabulate f = Cons (f 0) (tabulate (f . (+1)))

index (Cons b bs) n = if n == 0 then b else index bs (n - 1)

It’s interesting that you can implement a single memoization scheme to cover a whole family of functions with arbitrary return types.

Representability for contravariant functors is similarly defined, except that we keep the second argument of C(-, a) fixed. Or, equivalently, we may consider functors from Cop to Set, because Cop(a, -) is the same as C(-, a).

There is an interesting twist to representability. Remember that hom-sets can internally be treated as exponential objects, in cartesian closed categories. The hom-set C(a, x) is equivalent to xa, and for a representable functor F we can write:

-a = F

Let’s take the logarithm of both sides, just for kicks:

a = log F

Of course, this is a purely formal transformation, but if you know some of the properties of logarithms, it is quite helpful. In particular, it turns out that functors that are based on product types can be represented with sum types, and that sum-type functors are not in general representable (example: the list functor).

Finally, notice that a representable functor gives us two different implementations of the same thing — one a function, one a data structure. They have exactly the same content — the same values are retrieved using the same keys. That’s the sense of “sameness” I was talking about. Two naturally isomorphic functors are identical as far as their contents are involved. On the other hand, the two representations are often implemented differently and may have different performance characteristics. Memoization is used as a performance enhancement and may lead to substantially reduced run times. Being able to generate different representations of the same underlying computation is very valuable in practice. So, surprisingly, even though it’s not concerned with performance at all, category theory provides ample opportunities to explore alternative implementations that have practical value.

Challenges

- Show that the hom-functors map identity morphisms in C to corresponding identity functions in Set.

- Show that

Maybeis not representable. - Is the

Readerfunctor representable? - Using

Streamrepresentation, memoize a function that squares its argument. - Show that

tabulateandindexforStreamare indeed the inverse of each other. (Hint: use induction.) - The functor:

Pair a = Pair a a

is representable. Can you guess the type that represents it? Implement

tabulateandindex.

Bibliography

- The Catsters video about representable functors.

Next: The Yoneda Lemma.

Acknowledgments

I’d like to thank Gershom Bazerman for checking my math and logic, and André van Meulebrouck, who has been volunteering his editing help throughout this series of posts.

Follow @BartoszMilewski

July 29, 2015 at 11:48 pm

Where you say “It requires that there be an object a in C; one natural transformation α from C(a, _) to F;” F is any functor?

July 30, 2015 at 10:16 am

F is the functor from the definition: “any functor that is naturally isomorphic to the hom-functor, for some choice of a, is called representable.” I’ll edit it to make it clrearer.

September 13, 2015 at 6:37 pm

Hello! Suppose that for a fixed “a” in C(a,-) there are two objects, “x1” and “x2″, for which there are no arrow from ” a”. This means that Hom functor maps these object to empty sets. My question is: are these empty sets considered to be the same object in Set or are they distinct Set objects (albeit with the same internal structure)?

September 13, 2015 at 7:35 pm

@Leonid: There is only one empty set in Set.

September 9, 2017 at 12:40 am

I cannot compile the Representable class. I get the error:

• Illegal family declaration for ‘Rep’

Use TypeFamilies to allow indexed type families

• In the class declaration for ‘Representable’

Is that caused by a change in Haskell syntax since this blog post was written?

September 9, 2017 at 2:18 pm

Lots of Haskell features are optional, so you have to invoke them at the top of the file. In this case, the compiler tells you to use the

TypeFamiliesoption. It means you should put this line at the top of your file:{-# LANGUAGE TypeFamilies #-}February 5, 2019 at 7:00 pm

Confused by what qualifies as a “set-valued functor”. The examples provided in this chapter are List and Stream which are objects in Hask, not Set, no?

February 5, 2019 at 9:32 pm

Hask can be treated as Set, if you ignore the bottom. If you want to be really rigorous about it, it’s not even clear if Hask is a category. I’m glossing over these issues, since I use Haskell mostly as a source of intuitions for explaining category theory.

March 21, 2019 at 2:33 pm

I have made another example of representable functors: a game tree. Here’s the code:

{-# LANGUAGE TypeFamilies #-} module Main where -- Game Tree for the 8-puzzle data Moves = LFT | RGT | UP | DOWN deriving (Show, Enum, Bounded) data State = S { zeroX :: Int , zeroY :: Int , board :: [[Int]] } deriving Show class Representable f where type Rep f :: * tabulate :: (Rep f -> x) -> f x index :: f x -> Rep f -> x data GameTree m a = Node a [GameTree m a] instance (Bounded m, Enum m) => Representable (GameTree m) where type Rep (GameTree m) = [m] tabulate f = Node (f []) [tabulate (f . (mv:)) | mv <- [minBound .. maxBound]] index (Node x ts) [] = x index (Node x ts) (mv:mvs) = index (ts !! fromEnum mv) mvs -- Aux functions: makeMoves :: State -> [Moves] -> State makeMoves s [] = s makeMoves s (mv:mvs) = makeMoves (move mv s) mvs move :: Moves -> State -> State move dir (S x y b) = (S newX newY b') where b' = swap val b val | inBound newX && inBound newY = (b !! newX) !! newY | otherwise = 0 (newX, newY) = addTuple (x, y) (pos dir) swap :: Int -> [[Int]] -> [[Int]] swap val = map (map change) where change sij | sij == val = 0 | sij == 0 = val | otherwise = sij inBound :: Int -> Bool inBound x | x >= 0 && x <= 2 = True | otherwise = False addTuple :: Num a => (a, a) -> (a, a) -> (a, a) addTuple (x1, x2) (y1, y2) = (x1+y1, x2+y2) pos :: Moves -> (Int, Int) pos UP = (-1, 0) pos DOWN = ( 1, 0) pos LFT = ( 0, -1) pos RGT = ( 0, 1) initBoard = [[3, 2, 5], [4, 6, 0], [7, 8, 9]] initState = S 1 2 initBoard gameState :: (GameTree Moves State) -> [Moves] -> State gameState t = index t main = do let gameT = tabulate (makeMoves initState) :: GameTree Moves State print $ gameState gameT [UP, LFT, DOWN, DOWN, RGT]August 18, 2019 at 8:44 pm

In the original text:

Why do we need

[12]here?his only a Lambda function. Soalpha honly returns another function. I am thinking aboutinstead.

What have I missed?

August 18, 2019 at 10:22 pm

Have you tried compiling it? The compiler will tell you if you’re right or wrong.

August 19, 2019 at 1:38 am

Prelude> {-# LANGUAGE ExplicitForAll #-}

Prelude> :{

Prelude| alpha :: forall x. (Int -> x) -> [x]

Prelude| alpha h = map h

Prelude| :}

:24:11: error:

• Couldn’t match expected type ‘[x]’

with actual type ‘[Int] -> [x]’

• Probable cause: ‘map’ is applied to too few arguments

In the expression: map h

In an equation for ‘alpha’: alpha h = map h

• Relevant bindings include

h :: Int -> x (bound at :24:7)

alpha :: (Int -> x) -> [x] (bound at :24:1)

I’ve got a feeling that a Haskell function output type is only dependent on the right side of

->. It is[x]in the above case. I missed the “axiom” :-)))August 19, 2019 at 1:45 am

Replace

Prelude> {-# LANGUAGE ExplicitForAll #-}

with

Prelude> :set -XExplicitForAll

in above for GHCi

November 27, 2019 at 7:48 am

A new observation:

In addition to treating the representing type a as a logarithm, I found that it can also be seen as sqrt when we dealing with contravariant functor C(- -> a).

This means that

1. If F is a contravariant representable functor, then the representing type a = sqrt[x] {Fx}.

2. If F is an exponential type A^x , then the representing type a must be A. (because a = sqrt[x] {A^x} = A)

3. If F is an product type like A^x * B^x * … , then the representing type a must be AB…. (because a = sqrt[x] {A^x * B^x * …} = AB…)

4. If F is an sum type, then it is not representable.

For Hask category, it doesn’t seem to make much sense, because the only way to construct contravariant functor is using (->).

March 27, 2020 at 12:26 am

The notes make a claim:

“We will see later that a natural transformation from C(a, -) to any Set-valued functor always exists”

I’m not sure I understand it. If F is a Set-valued functor and F a is the empty set then you don’t have any natural transformations from C(a, -) to F (by Yoneda). In particular if you take F to be the constant functor to the empty set then you have no natural transformations for any object.

March 27, 2020 at 8:27 am

You’re right. I’m going to change it to “as long as F a is non-empty”. Thanks!

September 7, 2021 at 8:03 am

L.S.,

I’m struggling with the Stream (tabulate) instance.

Creating a ‘Stream Integer’ and then running ‘index’ is working 0K.

But I can’t get ‘tabulate’ to work.

As far as I understand ‘tabulate’ will create a ‘Stream Integer’

based on a function (Integer -> Integer ??)

I probably also need it for challenge 4.

Even with the help of the working Game Tree code of Fabricio O de França

(@fabriciolivett) A beautiful example, thank you Fabricio.

So my question is how do I need to call ‘tabulate’?

What parameters does it need, what types?

September 7, 2021 at 10:30 am

You understand it correctly. The trick is that the tail of the stream is the result of a call to tabulate, but with a slightly different function. You have to figure out what this function is.

September 7, 2021 at 3:30 pm

Thank you Bartosz!

I did have working functions to tabulate. (no spoilers 😉

But I did forget explicit type declaration of the tabulate result.

So NOT working:

result = tabulate tfunc

Working:

result = tabulate tfunc :: Stream Integer

November 12, 2021 at 2:55 am

I think the answer to Challenge 2 is that there is no natural transformation from

MaybetoC(a, -), therefore there can’t be a natural isomorphism between the two, thereforeMaybeisn’t representable. Such a natural transformationalphawould be a family of functions (since we are in Set), one for each objectxinC, such thatalpha_x :: (Maybe x) -> (a -> x). Its naturality condition would be that for objectsx, yand a morphismffromxtoyinC, it should bealpha_y . (Maybe f) (Maybe x) = C(a, f) . alpha_x (Maybe x) <=> alpha_y . (Maybe f) (Maybe x) = f . alpha_x (Maybe x). This equality cannot hold however for somexfor which it isMaybe x = Nothing: The left hand side would bealpha_y Nothing, which is a specific function inC(a, y), whereas the right hand side would bef . alpha_x Nothing, which is a different function for varyingf, therefore for any choice ofalpha_x, alpha_ythere is somefsuch that the equality breaks, therefore there is no natural transformation fromMaybetoC(a, -). Is my thinking right?On the other hand, I have a problem with

Nothing. In particular, @BartoszMilewski said “Hask can be treated as Set, if you ignore the bottom”. And there is no element inSetthat is mapped toNothingbyMaybe(even the empty set can be mapped toJust {}). I believe one can find a natural isomorphism betweenMaybeandC(a, -)ifNothingis ignored. And, since it never appears when the source category isSet, we can indeed ignoreNothing. Does this mean that, when specificallyC = Set,Maybeis actually a representable functor?January 29, 2022 at 5:57 am

Challenge 6

This is a pair of elements with the same type.

Since there are only two of them, we need a key with two possible values, e.g. Bool.

Since any function with Bool as its argument type can have only two possible possible values, all we need to tabulate it is to apply the function to True and False.

data Pair a = Pair a a instance Representable Pair where type Rep Pair = Bool tabulate f = Pair (f True) (f False) index (Pair x1 x2) b = if b == True then x1 else x2